Eminent sociologist and anthropologist MN Srinivas didn’t just study Indian society—he cracked it open. He forced India to see caste and social mobility with fresh eyes, working not from an ivory tower but in villages. As a founding father of Indian sociology, he shone light on the ground realities of social power structures—armed with what he called “a deep streak of scepticism towards all theorising”.

“Srinivas would always give you tremendous insight into what was the realist understanding of society. So, I would say, his greatest strength was that his feet were firmly on the ground—though sometimes in class he would put up his feet on the chair,” said Veena Das, professor emeritus of anthropology at John Hopkins University and a student of MN Srinivas at Delhi University.

Born in 1916 in Mysore, Srinivas upturned how Indian society was studied. He rejected the reliance on Sanskrit texts and theoretical abstractions that imagined India from a distance. Instead, he championed fieldwork, walking into villages to observe, participate, and document everyday life to essentially see how Sanskritic texts were diffused in everyday life practices. This approach, inspired by British anthropologist BK Malinowski’s ethnography, was reimagined by Srinivas to tackle the tricky challenge of studying one’s own society.

He introduced concepts like ‘Sanskritisation’, his analysis of how marginalised castes adopt practices of higher castes to climb the social ladder. These ideas were based on ethnographic evidence “rather than being politically guided by the present nationalistic moment then,” said Das—and are still central to understanding caste dynamics today.

Another influential idea Srinivas introduced was that of “dominant castes”, groups that wield social and economic power and shape local politics. His books—such as Religion and Society Among the Coorgs (1952), Social Change in Modern India (1966), and The Remembered Village (1976)— brought these concepts to life and were more accessible than much of the academic writing of his time.

“He recognised very well that sometimes our own familiarity blinds us to facts, and that we are not necessarily knowledgeable about our society,” Das told ThePrint. “While we have a familiarity with it, we often don’t see what’s before our eyes.”

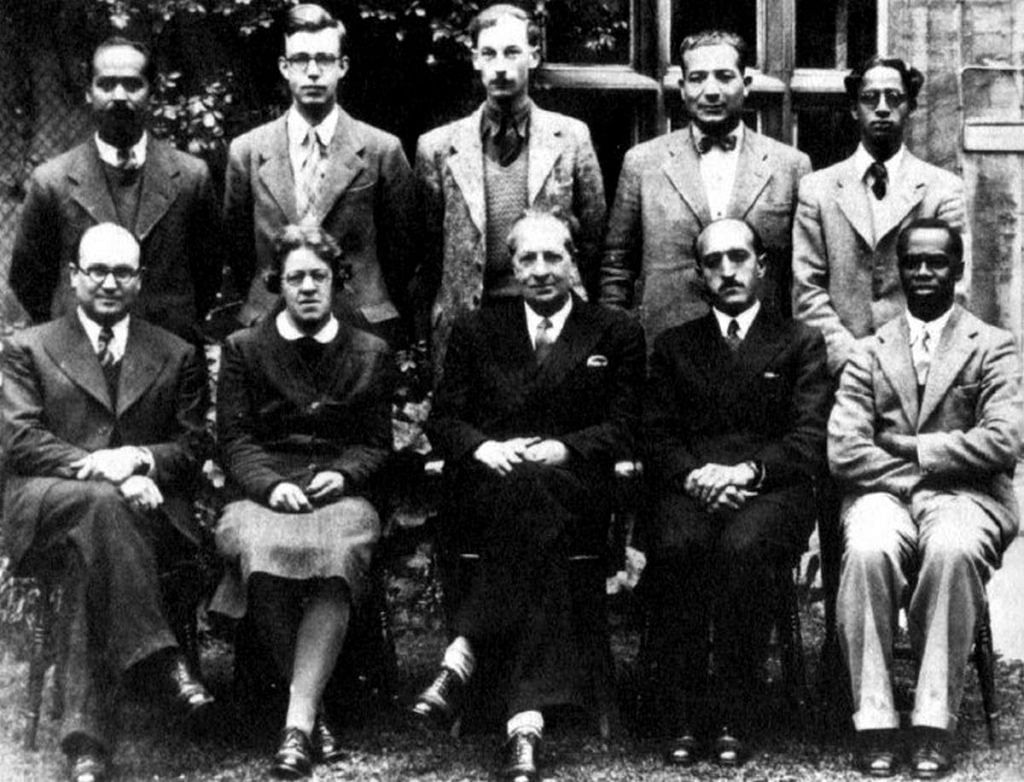

Over his career, Srinivas held a fellowship at Oxford, founded the sociology department at Delhi University, received a Padma Bhushan, and wrote or contributed to over a dozen books. Yet, those who knew him praised his humility the most.

“He was very approachable and never arrogant, as scholars can often be,” said his daughter Tulasi Srinivas, an author and professor of anthropology at Emerson College in Boston. “My father has only ever been critiqued for his ideas and never as a human being. Isn’t that incredible?”

Also Read: Plants to physics, JC Bose showed the world India had its own way of doing science

An ‘escape’ into academia

As a student, MN Srinivas didn’t enter sociology out of passion, but as an “escape”. In a 1999 interview, he admitted it was a way to avoid the pressure of taking a competitive exam for a government job.

“I was the youngest of four sons. I had lost my father when I was still in my teens and the family circumstances were somewhat straitened. Since I was considered bright, it was hoped I would take the competitive examinations and enter the provincial civil services. I was terrified by the prospect,” he said.

With no first-class degree in social philosophy to show for his BA, Srinivas dreaded the idea of another failure. So, in 1936, he headed to Bombay to study sociology under GS Ghurye, a towering figure in the field. But what began as a stopgap quickly became a calling as Srinivas discovered his knack for fieldwork and analysis.

After Independence, when Indian nationalism was still at its peak, Srinivas stood apart from many of his academic contemporaries. While scholars like Ghurye advocated for the assimilation of scheduled tribes into mainstream Hindu society through Hinduisation, Srinivas rejected such top-down solutions. Instead, he pointed to the complexities of local ties, such as those between tribal chiefs and Rajput kings—where ‘Rajputisation’ allowed tribal leaders to claim land, power, and status.

“He was very interested in questions of how would we build a fair and just society, but he didn’t think that somebody from the top could just dictate how that should be done. That was the big difference between him and a lot of other thinkers of his time who thought, ‘we are the enlightened ones, we know best how this should be done,’” Das said.

According to her, Srinivas believed in creating conditions in which people could speak about their own diverse experiences—and that their voices would be a better guide to addressing questions about social justice.

“He was not only a person of that time, but also beyond that time,” Das added.

An exacting but generous teacher

As a teacher, Srinivas inspired his students to think independently and challenge ideas—even his own. He was always attuned to not what he wanted students to do, but their own goals and how he could help them.

“He created an environment where we felt we could do anything,” Das said. She recounted how Srinivas once found a letter from Claude Levi-Strauss addressed to her and expressed curiosity about it. After she explained it was a response to something she had written on his notion of social structure, Srinivas encouraged her to present a seminar on Levi-Strauss for the faculty.

“I thought about it, and I did it!” she added.

Das described him as both encouraging and also “amazingly critical”. He would quickly catch on if a student spoke with mastery over jargon but without any evidence-backing, with little tolerance of such laxity. However, he was open-minded to feedback in the other direction too.

“When he published Social Change in Modern India, I did a critical review of it. He said that it was pretty ironical that when his book was receiving so much praise, the first critical review should come from his student. But he also said that it is the happiest thing in the life of a teacher when his students learn enough to criticise his work so sincerely,” Das said. “He showed me what it is to be a teacher.”

Also Read: Lipid disorders to sweetener—Chemist Sukh Dev blended ancient wisdom and modern science

‘Curious as a child even into 80s’

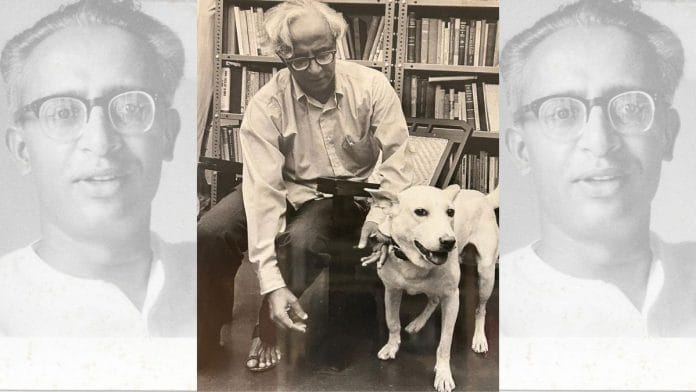

Empathetic observation was a crucial part of MN Srinivas’s personality—and “that’s what made him such a good ethnographer,” said his daughter Tulasi.

Growing up, his two daughters saw him live his passions and became part of it. Both Tulasi and Lakshmi Srinivas also built distinguished careers in anthropology and sociology.

“I used to work as a chartered accountant, but my father’s influence was such that I would often go and talk to people and they would tell me their stories, because I was somehow accidentally approaching them as an ethnographer,” said Lakshmi Srinivas, his elder daughter and a sociology professor at the University of Massachusetts. ”It felt like coming home when I finally landed up in sociology. Ethnography was his default way of operating; he created an environment at home accordingly.”

As someone who’d made decoding lived realities his life’s work, Srinivas loved being connected to the ground literally and figuratively. He preferred trains and buses over flights, relishing the chance to gaze at the Indian countryside and make cultural stops along the way.

The small things delighted him—admiring temples in South India, or the smell of coffee. Family trips often came with impromptu lessons in history and trivia.

“He was a Mysore boy,” Lakshmi Srinivas said. “We would go around in Mysore on tongas, and he would tell us a background history of every landmark or statue on the way.”

Longer trips in the region were no different, given Srinivas’s encyclopaedic knowledge of seemingly every mofussil town enroute.

“He’d get into the did-you-knows,” said Tulasi. “Like how Bidadi town got its name as a campsite for Tipu Sultan’s army and what it means for the people there. Or how another town is famous for its vadas and bhondas (fried snacks). “These were normal conversations for us growing up.”

At home, disagreement was not just tolerated but encouraged. Srinivas didn’t want people to just agree with him as he found that very “boring”, said Tulasi.

His wife, Rukmini Srinivas, who affectionately referred to him as Chammu in her memoir, Rambling with Rukka, told ThePrint that he was very “nimble” and “would run up and down the stairs even when he was 80.”

And he was also flexible in his thinking.

“He was always open to new ideas, and to our youthful stupidities, to engage us,” Lakshmi said, adding that growing up they never felt the age gap and “he was just like us, very youthful”.

The Srinivas household was anything but patriarchal and all members were encouraged to take their own decisions.

“He would always let us do things our way, and we would find out as we went along—that was the kind of parenting with Appa. He was not a disciplinarian. We were never scared of him. He would joke a lot and had a mischievous sense of humour. He would pull all our legs, and we would pull his leg, too,” said Lakshmi.

On 30 November 1999, MN Srinivas died at 83 following a lung infection. His final public lecture had taken place just a month earlier at the National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bengaluru. The topic was “Obituary on Caste as a System,” and, even then, he offered fresh insights.

“He was curious like a young child even into his 80s,” said Lakshmi.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Great article. ThePrint should also put this in video format on their YouTube channel.

While I’m proud of this byline, I have one regret…

I forgot to include a section about his RESILIENCE. It was all in my notes. Had I been a bit more organised, this would have been the cherry on top:

MN Srinivas was very “resilient”, Rukmini said.

In an anecdote from her memoir, “Out of Fire, Rebirth”, based on a speech she wrote for an American Anthropological Association conference on his 100th anniversary in 2016, titled, “Remembering Chammu: A Study in Resilience”, Rukmini talked about how despite being devastated after losing his mother who was ill, and decades worth of field notes to arson at the University of Chicago within a span of 48 hours—notes which he had made during his ethnographic study of a village named Rampura (Kodagahalli), Karnataka—Srinivas didn’t give up on his project. He wrote a book on his field from sheer memory, The Remembered Village.

“What hangs in Chammu’s library and study in our home in Bangalore is a memento, a framed drawing of a magnificent Phoenix rising from the fire”, said Rukmini in her speech.

Srinivas’s sense of humour was such that he acknowledged and thanked the arsonists, the ROTC protesters who found no other avenue but arson for their opposition to the Vietnam war in his book.

—

It is ironic, and I feel so sad about not remembering to include this, but it’s a learning experience.