In 1957, while India celebrated Satyajit Ray’s Aparajito winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and Mother India becoming the country’s first Oscar-nominated film, a 32-year-old filmmaker chose to look beyond the euphoria.

Guru Dutt, rather than celebrating the nation’s achievements, turned his camera to the darker, more painful realities plaguing a country that was just 10 years into Independence.

He wrote, directed, and acted in a movie that would go on to become a cult classic, portraying a young man’s angst in coping with a materialistic world. In Pyaasa (1957), Dutt portrayed the heartache of Vijay, a disillusioned poet wandering through a red-light district, asking India’s leaders: “Where are the guardians of dignity? Where are those who take pride in India?”

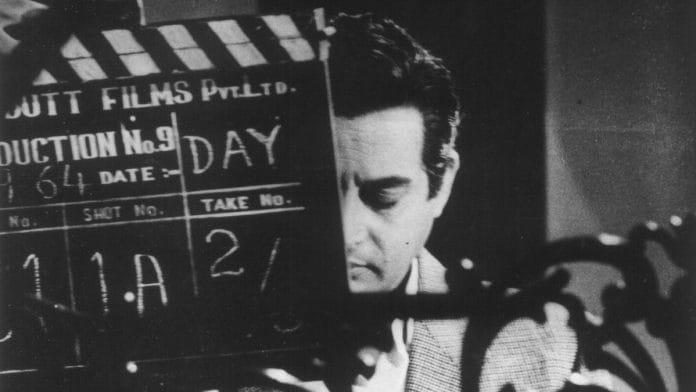

It was a bleak masterpiece—the questions it raised remain relevant even today. It was also a reflection of the man himself. The Hamlet of Films, the melancholic hero, Dutt’s allure has only grown after he died at the age of 39 on 10 October 1964.

In the documentary In Search of Guru Dutt (1989), his son, Arun Dutt, recalled his father’s “morbid thought process”, which he said was almost always negative with an emotional intensity that often left him isolated, “eating himself from inside out”.

The Hamlet of films

Dutt’s life was as tragic and enigmatic as the characters he brought to life on screen.

Called the “Hamlet of Films”, Guru Dutt was born Vasanth Kumar Shiv Shankar Padukone, on 9 July 1925 in Padukone, Madras. An introvert who was “extremely reserved”, he chose to express emotions through his work.

“You couldn’t read through him, but I read one thing: He was really lost —in filmmaking, lost to life,” director Raj Khosla said in the documentary on Dutt.

Dutt began his career with Navketan’s Baazi (1951), influenced by American noir, which transformed Dev Anand’s image into a more complex, grey character. Despite his success with hits like Aar-Paar (1954) and Mr. & Mrs. ’55 (1955), Dutt remained introspective and restless, questioning stardom and preferring films with deeper, more personal subjects over those aimed at commercial success.

In a rare 1957 Filmfare interview, Dutt described how his art became a refuge for his wandering soul: “When I joined films, the wanderer in me was put into solitary confinement, and the door of my ‘prison’ was opened only after the release of Pyaasa.”

Dutt’s cinematic works were ahead of their time, reflecting the contradictions of modern India: A nation struggling to reconcile its material aspirations with its spiritual and emotional complexities.

Dutt explored a wide range of genres, from neo-noir and adventure films to romcoms and social dramas, according to Yasir Abbasi, author of Yeh Un Dinoñ Ki Baat Hai: Urdu Memoirs of Cinema Legends (2018). However, he is best remembered for his stunning use of light and shadow during the era of black and white cinema.

Along with cinematographer VK Murthy, Dutt created iconic imagery replete with light and shadow sequences which are considered pathbreaking, such as the Christ-like shots in Pyaasa and the “mirror shot” in Kaagaz ke Phool– India’s first cinemascope film.

Cinematographer Baba Azmi once credited Dutt for learning the art of Chiaroscuro, playing with light and shadow.

Vinay Shukla, the director of Godmother (1999), highlighted in an interview how the actor’s choice of themes were personal but timeless.

“When you look back, the themes he [Dutt] picked up in his films don’t age. In Guru Dutt’s films, external behaviour of the characters didn’t matter as much as their inner turmoil. The hallmark of his narration was his intensity and that of his style was simplicity and minimalism”, Shukla said.

His characters, like Vijay from Pyaasa or Suresh from Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), were caught between dreams of a better life and the harsh realities of their surroundings. They embodied a profound sense of disillusionment with society, mirroring Dutt’s sense of alienation.

In his book Guru Dutt: A Tragedy in Three Acts, critic Arun Khopkar noted that the actor’s films reflect an inner turmoil that transcended his personal life, elevating his work to something deeply universal.

“When the will to destroy the self expresses itself not through the actual act of self-destruction but through a work of art — which is haunted by the visions of self-destruction — it is lifted out of the ambit of personal life,” he wrote.

Perhaps this is why his cinema continues to inspire. Director Anurag Kashyap has cited the song Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaaye To Kya Hai from Pyaasa as an inspiration for his 2009 film Gulaal. R Balki’s Chup: Revenge of an Artist (2022) was a tribute to the cinematic genius of Dutt.

The dissatisfied artist

Isolation became the hallmark of Dutt’s personal and professional life.

“His nights were spent with whiskey and words printed on paper. Guru Dutt was perhaps living inside a box that was so dark that no one could see his pain, so dark that even he could not see a way out of it,” Yasser Usman wrote in his 2021 book, Guru Dutt: An Unfinished Story.

He attempted to take his life thrice, once ending up in a coma for three days. When he died at the age of 39, many called it a suicide. His son Arun Dutt said it was a case of drug overdose. He had meetings planned the next day and had not left a note, unlike the other two attempts.

Dutt’s last night was spent pining to meet his children and discussing what he loved the most – cinema.

“…That night, he just approved of the last scene; bade me goodbye, and then, after locking himself up in his room, quietly quit this world when dawn was just around the corner. That cruel night spirited away his restless soul,” director Abrar Alvi said in a 1966 Filmfare interview.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)