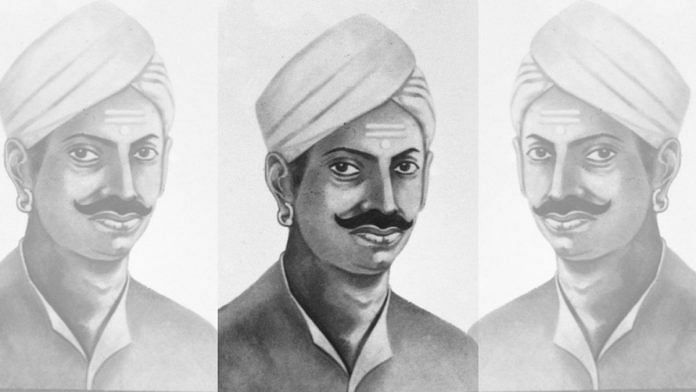

It was nearly the end of Spring in Bengal, March never looked more serene. In Barrackpore, Kolkata, 34th Native Infantry sepoy Mangal Pandey marched outside the regiment guard’s room with a loaded musket. He was agitated. And as adjutant Lieutenant Henry Baugh, who was on horseback rode toward him, Pandey took a shot but missed.

A scuffle broke out between Baugh, Sergeant Major James Hewson, and Pandey, who drew his talwar. Commanding officer Steven Wheeler ordered the jemadar to arrest Pandey but the fellow sepoys made no move. Pandey, in their eyes, was already a hero for daring to mutiny. But he was finally seized, tried, and subsequently hanged on the 8th of April.

Pandey’s place in history has triggered a long string of historical debates for decades. Even today, one has little to no precise knowledge about the man behind the legend. Historian Rudrangshu Mukherjee in his book Mangal Pandey: Brave Martyr Or Accidental Hero? brands him “an unexpected intrusion into history”.

British papers said “a sepoy has heavily drugged himself and run amock” in reference to Mangal’s rebellion. And it reflected British attitudes towards Indians, who they considered primitive and disorderly. They viewed his mutiny in purely orientalist terms. Mangal Pandey was tried by a court marshall, but he remained silent throughout.

Subaltern historians conclude that his silence was calculated and defiant. When asked if he had acted of his own free will or instructed by others, Pandey promptly replied that he had single-handedly orchestrated the act of rebellion and expected to die. His comrades even offered to set him free but Pandey refused. “Let them try me. the British make a great deal out of their system of justice. I want to show the world the farce of the British judicial system,” Pandey had said.

Also Read: 1857 Indian uprising to Galwan clash: How Army’s Bihar Regiment demolished ‘non martial’ tag

Accidental hero or a flag bearer

British papers and colonists dismissed Pandey’s act of rebellion by saying that he mutinied in “a drug-induced haze”. A general discontentment was already brewing in the sepoy barracks but the British failed to pick up on its gravity. It soon spiralled into dissent and open rebellion—and Mangal Pandey became its face.

Mukherjee, however, recognises Pandey’s unwavering solidarity with his fellow sepoys. Midnight meetings were attended by sepoys from different regiments but during his trial, Pandey refused to name those who were implicated. He only had one answer, that he had acted on his own. Mukherjee writes, “The collective aspect was again made evident when the sepoys of the 34th, Mangal Pandey’s regiment, trampled their caps on the ground when they were disarmed, a gesture of protest carried out collectively, which would in a month’s time transform itself to more violent and concrete forms.”

His death was mourned by sepoys throughout Bengal. Pandey’s single act of revolt had spurned a bigger revolution in Meerut a month later. He was perhaps the first sepoy to dissent and even the Britons made an example of him by calling all other rebellious sepoys ‘pandies’.

It’s hard to tell if his revolt was the tipping point of the iceberg and solidified his status as a national hero. But he contributed to the start of the movement more than the Britons were willing to admit.

Also Read: Abdul Hamid’s bravery in destroying Pakistani tanks at Asal Uttar ensured his legacy

Pandey in popular culture

In a country where memorials and statues of freedom fighters decorate urban cities and towns, one finds Pandey’s familiar face missing. However, information related to his life is scarce and oscillates between dismissal and myth-making. Some say he had a love interest in Bengal who he vowed to protect, while other myths paint him as a volatile individual. Awadhi text Aalha Mangal Pandey narrates how his comrades called him a ‘love-struck bird’ too unfit for combat.

The status of ‘national hero’ attached to his name also seems to be contested among historians. But he was immortalised by Bollywood in an Aamir Khan starrer Mangal Pandey: The Rising. The filmmakers did not manage to handle historical facts accurately but it was a fine attempt to reconstruct the life of a sepoy trying to dissent against British rule. The film was an attempt to mix history with folklore. While the movie in itself does not address the sepoy mutiny, it creates a narrative suitable for an audience who craves a slight dramatisation of the event, which many would say, changed the course of Indian history.

In his book Mangal Pandey: True Story of an Indian Revolutionary, writer Amaresh Misra claims that the rebel sepoy actually triggered the First war of Independence. Misra’s text attempts to refashion Pandey’s story and is an insight into what went behind cultivating him as a national figure. Misra also speaks of Pandey’s village, which was in shambles when the British accelerated their move to de-industrialise. This is where Pandey slowly comes to terms with the downsides of colonialism—he goes from a starry-eyed young army recruit, claims Misra, to perhaps India’s first freedom fighter.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)