New Delhi: “A king who would rather have been a poet, scion of a once-wealthy dynasty who would rather have been a mystic.” So goes the description of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, in professor Pramod Nayar’s The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar, which reproduces the text, documents and accounts of witnesses related to his role in the Revolt of 1857.

By the time Bahadur Shah Zafar ascended the throne, the area under Mughal rule was drastically reduced, as were the emperor’s powers, symbolic and otherwise. He was ultimately known only as the ‘King of Delhi’. Despite this, the sepoys looked to him as their one leader against the British and approached him for assistance in the mutiny. Zafar, as his pen name goes, was also known to be among the most tolerant and peace-abiding rulers, and his religious neutrality is also said to be a reason the sepoys considered him their mascot.

On his 157th death anniversary, ThePrint examines Bahadur Shah Zafar’s role in the 1857 mutiny, the contested history of the times and the trial of the last Mughal.

Also read: The ruin of Zafar Mahal: Mughal era’s last holdout is now a den of drug addicts and gamblers

The last Mughal’s last days

The introduction to H.L.O. Garrett’s book, The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar, poses a pertinent question: What was the actual end of the Mughal rule? Was it in 1707, with the death of Aurangzeb at Alamgir or in 1717, when a Mughal firman waived all customs duties for inland trade? Or in 1816, when Lord Hastings abolished Mughal currency and made the British rupee the currency of the land?

The argument made is that the Mughal rule fell much before 1857, before the imprisonment and humiliation of Bahadur Shah Zafar, but what his exile and subsequent death actually signified was the death of hope, as symbolised by the Mughal empire.

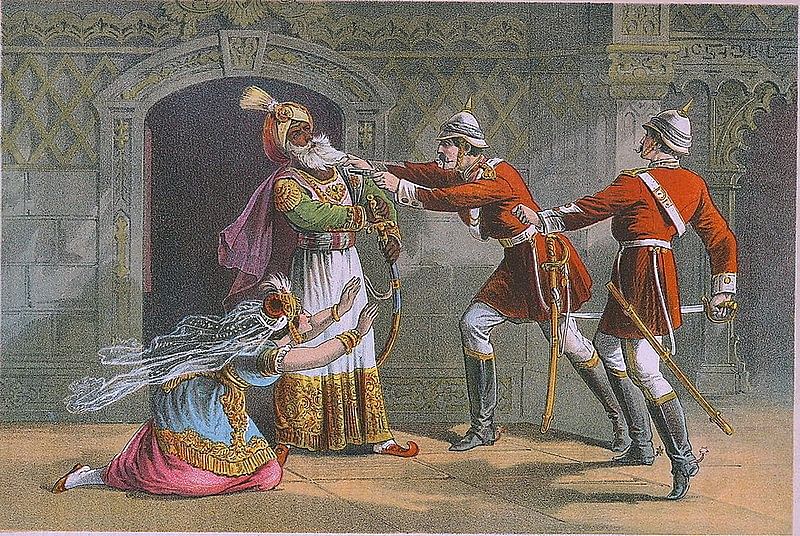

On 19 September 1857, the emperor was arrested from Humayun’s Tomb along with some of his wives and princes. There are contested histories of the time. Mahmood Farooqui’s Besieged Voices From Delhi 1857, is a lot kinder to the emperor, stating that he was an indispensable symbol of the revolution despite being a reluctant martyr. And without him there would be no moral authority under which a settled administration could emerge and troops could be rallied.

The book also states that even with the Mughal empire at its weakest (it only extended to Delhi and Palam), he was still the ‘Baadshah of India’. Farooqui goes on to speak about the self-awareness of the emperor who knew that he would be the last Mughal ruler to live in the Red Fort and the innovative means of establishing his dominance and getting his way — by threat of asceticism, abdication or vanishing into the palace until his demands were met.

Garrett, however, writes that the emperor surrendered only with the promise that his life would be spared. That he showed cowardice by hiding in Humayun’s Tomb while it was his sons who were fighting the British, two of whom (Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan) were shot dead by William Hodson at Khooni Darwaza. The introduction of his book further states that the only respectable thing Bahadur Shah Zafar did during his trial was nap in between and that although his testimony had the potential of being a final tribute to the extraordinary heritage he inherited, it ended up only a “weasel’s lament”.

What, however, was not a weasel’s lament was his poetry. When he was captured by the British, ever the poet-king (whose pen name ironically means victory) belted out his shayari to a British officer: “Hindion mein bu rahegi jab talak imaan ki

Takht e London tak chalegi tegh Hindustan ki.”

(As long as Indians have even a ounce of honesty and dignity- the Indian sword will reach the throne of London).

The trial

The trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar began on 27 January 1858 at 11 am. He was tried for aiding and abetting the mutiny, establishing sovereignty of ‘Hindostan’, waging war against the British government and being an accessory to the murder of Christians.

In the trial transcripts, he is referred to as the ex-king of Delhi. The trial took place at the Red Fort, his residence, where he was made prisoner, and went on for 21 days. At the beginning of the trial, when asked if he was guilty or not guilty of the charges, Bahadur Shah Zafar could not understand what was being asked, although a translated copy of the charges was given to him 20 days before the trial began. And it was only much later that he broke his silence and pleaded not guilty.

As the trial progressed, he claimed to be absolutely unaware of all the orders and edicts that were passed using his signature and entirely blamed either his Commander-In-Chief Bakht Khan or the army, in front of whom he was “powerless”. At the trial, the emperor said, “The state of this army was such that nobody ever saluted me or showed any respect for me. They would march into the tasbihkhana or the Diwan-e-Khas with their shoes on. How could I trust an army that had killed its governors?”

According to William Dalrymple’s book the The Last Mughal, it was the emperor’s confidant and personal doctor, Hakim Ahsanullah Khan, who testified against him in exchange for clemency for himself. On 9 March 1858, the emperor was found guilty of all charges by the British court.

The British kept their word of not sentencing Bahadur Shah Zafar to death, but instead sent him, along wth some of his family, to exile in Yangon, Burma.

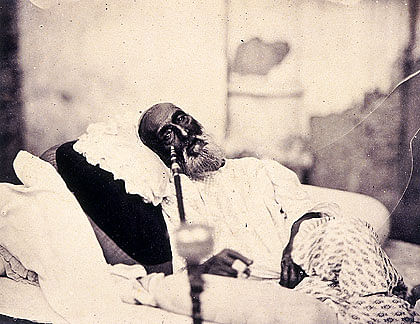

Dalrymple’s book quotes a British officer who saw him during exile: “I saw that broken-down old man – not in a room, but in a miserable hole of his palace – lying on a bedstead, with nothing to cover him but a miserable tattered coverlet. As I beheld him, so remembrance of his former greatness seemed to rise in his mind. He rose with difficulty from his couch; showed me his arms which were eaten into by disease and by flies – partly from want of water; and he said, in a lamentable voice, that he had not enough to eat.”

But even during his last days, Bahadur Shah Zafar’s poetry did not leave him. A ghazal he penned during his days in exile beautifully translates the anguished loneliness of the reluctant poet-king.

Bhari Hai Dil Mein Jo Hasrat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

Sune Hai Kaun Musibat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

Jo Tu Ho Saaf To Kuch Main Bhi Saaf Tujh Se Kahun

Tere Hai Dil Mein Kudurat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

Dil Usko Aap Diya Aap Ji Pashiman Hun

Ki Sach Hai Apni Nadamat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

Jo Dost Ho To Kahun Tujh Se Dosti Ki Baat

Tujhe To Mujhse Adawat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

Na Mujhko Kahne Ki Taqat Kahun To Kya Ahwal

Na Usko Sunne Ki Fursat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

Kisi Ko Dekhta Itna Nahin Haqiqat Mein

‘Zafar’ Main Apni Haqiqat Kahun To Kis Se Kahun

(How do I explain the unfulfilled desires inside me

Who will listen to my problems

If your heart was pure and clean I would talk to you

However your heart is full of impertinence.

While I do have regrets, whom do I explain them to?

If you were a friend, I would confide in you and speak to you like my own.

But all you have is hatred against me.

Neither do I have the strength to tell you about my condition

And nor are you interested in knowing it.

To whom can I express and explain my reality as Zafar)

Also read: A birthday tribute to Mirza Ghalib, the poet who took Urdu to the zenith of glory

Beautiful Poem. He helped the rebels and sepoys in 1857 revolt against British as per his power and strength. They called and declared him “King of India” indicates that he was a ruler of tolerance.

beautiful poetry

kitna hai badnasib zafar dafan ke liye

do gaz zamin bhi na mili ku-e-yaar me

lagta nahi hai dil mera ujde dayar me

What a sorry state of a Badasha! May be his love for the poetry kept him alive and sane.