Zulfikar Ali Bhutto once warmly received the two men, who hijacked an Indian Airlines plane to Lahore, and hailed them as national heroes. This was when the “false flag” became a weapon for the ISI to distance itself from terror operations with bad fallout: Chittisinghpora, Ishrat Jehan, Parliament, and now Pahalgam. The way this hijacking was constructed, and repeatedly reconstructed, helps understand this conspiracy theory narrative instrument.

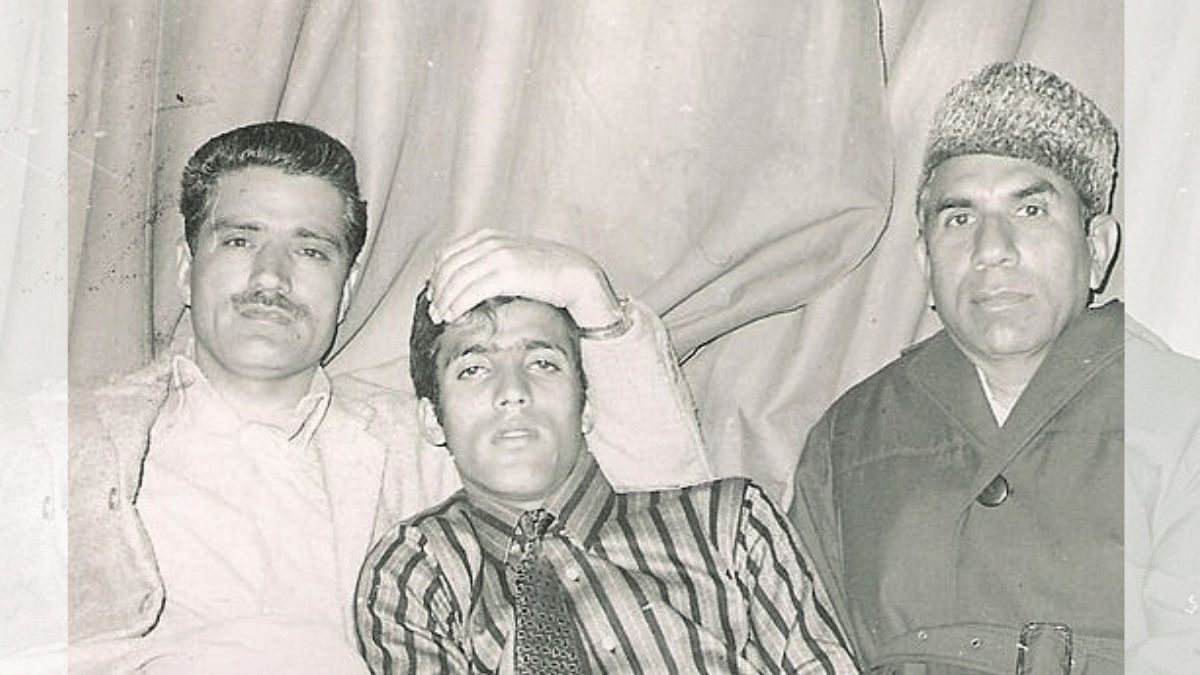

New Delhi: The photographs from that brightly lit winter afternoon at Lahore show a clean-shaven Hashim Qureshi dressed in a suit, tie and fedora hat. He’s shaking hands with a man in an impeccably tailored three-piece suit. We know what that photograph shows us from the memoirs of Lieutenant-General Gul Hassan Khan, Pakistan’s last Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the man in the three-piece, was equipped with, and I quote, “a rare sixth sense for the dramatic.” He’d heard of the unfolding crisis at the airport and promptly made his way there to get himself photographed. The man who would soon help spark off the 1971 war and then become Prime Minister of Pakistan, proceeded to embrace Hashim Qureshi as, and I quote, “true champion of the Pakistani cause”.

Hi and welcome to this week’s episode of ThePrint Explorer and a very special thank you to those of you who are regular viewers. As we film this episode, many in Pakistan have been claiming that the terrorist attack in Pahalgam was a false flag operation carried out by Indian intelligence services to defame the country.

Islamabad and its sympathizers have long used the false flag defense when confronted with evidence that its proxies are engaged in acts of terrorism. There was a time when 26/11 was called a false flag. The massacre of Sikhs at Chittisinghpora in 2001 ditto. The hijacking of an Indian Airlines flight to Kandahar? Meh, you guessed it. Attack on Parliament House was a false flag too, so the writer Arundhati Roy alleged. There’s a pretty long list, so I won’t go on and on and on and on.

What I’d like to do today is unpack the first case which injected the false flag idea into Pakistan’s narrative toolkit. Those two men in suits at Lahore airport, you see, both played a role in sparking off this 1971 war. And to many, it seemed convenient to later say the hijacking was staged by India to enable it to attack East Pakistan and bring about the vivisection of the country.

Great story, except on close examination, the great story makes very little sense, just like the false flag stories on 26/11 and Chittisinghpora and Parliament House. True, I should say right up front, nation states tell lies. False flag operations do take place.

Nazi Germany attacked the Gleiwitz Radio Station using its soldiers dressed up in Polish uniforms to provide a pretext for invading the country. There’s now pretty compelling evidence from declassified United States government documents that an alleged attack on its naval ships in the Gulf of Tonkin was fabricated to provide an excuse to bomb North Vietnam. The British dossier on Iraq’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction was “sexed up” to justify going to war.

I’m pretty sure Indian spies, just like all other spies, lie all the time. The question is, are they lying on this particular occasion? Who knows, perhaps papers will one day emerge from an archive that will show that everything I’m going to tell you about the story of the 1971 hijacking is all wrong. For all I know, perhaps Pahalgam will be proved to be a false flag attack.

But careful analysis of the story I think is of value because it teaches us to leave our emotions aside and look at the evidence with an open mind.

Also Read: 14 million displaced, thousands killed—Sudan civil war shows failure of global powers

The hijacking

At 1.05 p.m. on the 30th of January 1971, an Indian Airlines flight carrying 26 passengers and four crew made an unscheduled landing at Lahore airport. The Fokker F27-100 Friendship, an aging aircraft that had been withdrawn from service once already before being pulled out of retirement by Indian Airlines, had been hijacked by two men who claimed to be armed with a hand grenade and a pistol.

The hijackers were in fact armed with just wooden mock-ups. Those were, I suppose, less murderous times. Anyway, they wanted the release of 30 odd members of a Kashmiri secessionist group, the National Liberation Front, from Indian jails.

The 1960s and 1970s were busy decades for hijacking carried out by groups with all sorts of political grievances. And just in September 1970, not long before the Lahore hijacking, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine had simultaneously hijacked four airliners bound for New York and a fifth one bound for London and then blown up three of them at Dawson’s Field in Jordan. So the hijacking of Indian Airlines, Victor Tango, Delta Mike Alpha wasn’t the biggest geopolitical event on the planet.

A crisis was brewing around that hijacking though, one which made this single incident very special. At the end of 1970, general elections had been held in Pakistan and the Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had won 167 seats, a neat majority. That meant East Pakistan would have power over all of Pakistan.

Zulfiqar, who had won just 86 seats, convinced the military ruler General Yahya Khan to stop the new parliament from convening. This gave rise to deep unrest in East Pakistan and led up to the birth of the Bangladesh insurgency with consequences we all know. Towards the end of 1969, a young Srinagar resident named Hashim Qureshi, yes, one of the men on that tarmac, the well-dressed hijacker, had travelled to the Pakistani city of Peshawar in connection with arrangements for the marriage of his sister.

There he ran into the Kashmiri secessionist leader Maqbool Bhat, who had recently and spectacularly escaped from jail and fled into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Although Hashim Qureshi had little engagement with Kashmiri secessionist politics, he promptly volunteered to serve the National Liberation Front (NLF). I am guessing he was awestruck by Maqbool Bhat.

For some weeks before he returned home, Hashim Qureshi was given extensive education in NLF ideology and given some military rudimentary training. He became a tiny cog in a very small insurgent machine. But that was to prove enough, because of a number of things that happened, enough to become a hero for Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

To understand why this happened, you need a second bit of context. In November 1965, after the collapse of Pakistan’s effort to seize Kashmir through the use of irregular forces backed by its army, a small group of Kashmiri nationalists based in Muzaffarabad had decided they would go it alone, that they could do it better than the army could. Part of it was religious zeal, part of it was inspiration by Maoism, part of it was the impact of insurgencies, nationalist insurgencies waging underway across the world.

The NLF sent two groups to infiltrate from Pakistan-occupied Kashmir across what was then called the ceasefire line. Their hope was that through their armed actions, they would create a spark that would set off a popular insurrection. Led by Major Amanullah, a former soldier in Pakistan’s Azad Kashmir forces who hailed from the town of Kupwara, the first group was meant to train new recruits in the use of explosives and small arms, just like terror recruits are today trained.

Two other former soldiers, Subedar Kala Khan and Subedar Abibullah Bhatt, joined this group under Major Amanullah’s command. The second group led by Maqbool Bhat had the task of trying to find recruits to train. This turned out to be somewhat harder than they had expected.

Hashim Qureshi might have been very impressed by the NLF’s plans but quite few young Kashmiris were to prove to do so. The group crossed the ceasefire line in the summer of 1965 but was detected by the state’s police in less than two months. Together with one of his recruits, a person called Mir Ahmed, Maqbool Bhat was cornered by a police patrol.

Amar Chand, a police inspector, was killed in the shootout that followed. For a few hours in the autumn of 1966 where all this happened, it might have appeared to villagers near Sopore that war had broken out again. Shots were fired, and the firing went on for quite some length of time.

The shootout did make headlines but it was soon forgotten. It turned out to be a one-off incident that seemed of little consequence. “Least did anyone realise”, the journalist Sati Sahni later recalled, “that this would become a major turning point in Kashmir’s history”.

When Bhat and Mir Ahmad were given the death penalty by the court of sessions judge Neelkanth Ganjoo, there were no protests or demonstrations anywhere in Kashmir or outside. Late in 1968, Maqbool Bhat succeeded in escaping from jail and made his way back across the ceasefire line into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. There, of course, fate led Hashim Qureshi to his door and thus the hijack plot evolved.

A bungled hijacking

The NLF headquarters used an intermediary they considered a reliable courier to deliver weapons to Hashim Qureshi while they prepared for hijacking the Indian Airlines flight. That individual though turned out to be a double agent and handed the weapons over to the police. The hijackers Hashim and his cousin Altaf, however, remained committed to the hijack plot and fabricated mock-up weapons using wood and a block of soap.

A few minutes into the flight from Srinagar to Jammu, Hashim Qureshi entered the aircraft’s cockpit and branding his mock grenade took control. Altaf Qureshi remained in the cabin where he informed the terrified passengers that they had been hijacked. The hijackers had initially hoped to take the plane to Rawalpindi but a shortage of fuel forced them to land instead at Lahore.

There, speaking on behalf of the hijackers, NLF Front member Farooq Haider announced that the hijackers wished to be granted political asylum in Pakistan and guarantees that their families in Jammu and Kashmir would not be harmed. They also demanded the release of 36 prisoners held by India. From the moment they landed in Lahore though, things began to go badly wrong.

..When I reached my office, our crime reporter Pervez Chishti (whom we called Baba Chishti)told me to immediately reach Lahore airport as an Indian hijacked plane had landed there.I didn't have a motorcycle in those days. Instead I used my bicycle to ride through Lahore streets.. pic.twitter.com/OHbOPTyEdV

— Naimat Khan (@NKMalazai) September 19, 2019

Lahore’s administrative head Agha Ashraf, a civil services officer and an army officer present with him, Major Rahim Shah, persuaded Hashim and Altaf to release the hostages, which by the way to me is persuasive evidence Pakistan had no foreknowledge of the hijacking plot. The officers’ professional conduct though deprived the hijackers of any leverage they might have had with the Indian government. “We were very young”, Ashraf Qureshi was to ruefully recall later, “and did not realize that the passengers were more important than the actual plane”.

Then as more and more politicians arrived at the airport, things began to spin out of control. What happened next was vividly described by K. H. Khurshid, the former president of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, before a special court in Pakistan. When he arrived at Lahore on the evening of 3 February, Khurshid said, he was ushered into a room by the senior superintendent of police responsible for the airport security, Sardar Abdul Vakil Khan.

Inside the VIP room, Khurshid found Maqbool Bhat and Hashim Qureshi engaged in an energetic discussion with officials. Qureshi, it turned out, had been asked by the Pakistani authorities present there to burn the plane down. He instead suggested that some minor damage be inflicted to the plane’s body, hoping optimistically that this would give the Indian government some further time to consider the release of the prisoners.

Abdul Vakil Khan then implored Qureshi to do as he was told. ‘Khuda ke liye hamari jaan chhod do, jahaz ko uda do.’ For those of you who don’t speak Hindustani, that means, for God’s sake, spare our lives and destroy the plane.

As Khurshid waited in the room, Hashim was taken away by officers he did not know. Sardar Abdul Vakil Khan and Bakar Ali Shah, both officers, went with Hashim and joined the crowds milling around the airplane. As they did so, somebody began saying that the plane had been set on fire.

General Gul Hassan Khan writes that at the time it was widely rumoured that Bhutto himself gave the signal to the hijackers to blow up the plane. There is no hard evidence to support this proposition, but I guess the flamboyant theatrical gesture, the burning plane, made political sense for Bhutto.

An aggressive position on Jammu and Kashmir, after all, would have helped deflect attention away from the simmering crisis in the east and thus enabled Bhutto to unite his disparate West Pakistan constituency on a hardline nationalist platform. Bhutto, after all, had taken a consistently hawkish position on Kashmir, helped provoke the 1965 war, in fact, and constantly played the Kashmir card.

Also Read: Trump wants a new Yalta to assert American hegemony. History shows this grand plan will likely fail

Flying false flags

For some time, Hashim and Altaf Qureshi were treated as official heroes. In an official note, the Pakistan government sought to legitimise the hijacking, claiming it was, and I quote, “the direct result of repressive measures taken by the Government of India in occupied Kashmir”.

Then the war of 1971 happened. Pakistan lost and the hijacking was reinvented as a tale of Indian perfidy. The hijackers, along with several important NLF leaders, were then arrested, this time by Pakistan, after the realisation that, I quote from a Pakistani account, ‘Indian intelligence had stage-managed the hijacking’.

Yeah, false flag. Later, a judicial enquiry set up to consider the issue, held by a judge of the Sindh and Balochistan High Court, arrived at the same conclusion. While other NLF members were acquitted of treason charges on the ground that they had been ignorant of the larger conspiracy, Hashim Qureshi was to serve 7 years of a 13-year term before being released on a successful appeal to the Lahore High Court.

Hashim Qureshi would continue to play a key role in the NLF’s affairs after his release in 1982. Altaf Qureshi, for his part, had enough of politics. He pursued his education and then became an academic, rising to become Professor of Kashmir Studies at the Punjab University in Lahore.

The story, however, was nowhere near its end. In Pakistan and in India, conspiracy theories began to swirl around the hijacking. Mujibur Rahman claimed that the entire affair had been staged to provide a pretext for denying power to his party, the Awami League.

There were alternate claims by Kashmir leaders, including Chief Minister G.M.Sadiq and Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, that India had staged the crisis but to undermine Kashmiri nationalism. So, version flavour number 2 of the conspiracy theory. There are lots and lots of versions, and I am not going to spend time unpacking all of them.

We will just stick with the facts. For the first time in 1981, claims that Hashim Qureshi was actually an Indian intelligence agent were made in print in a book by the well-respected journalist B. M. Sinha. Sinha’s 1981 book, ‘The Samba Spying Case’, which is a great read by the way, claims that Hashim Qureshi was dispatched across the ceasefire line by the Border Security Force (BSF) to spy on Maqbool Bhat’s activities.

Soon after he made contact with the NLF though, and for reasons Sinha doesn’t go into, he switched sides. When he returned to Jammu and Kashmir in January 1971, according to Sinha, he was arrested by his former anglers. According to Sinha, Hashim Qureshi now told the BSF that he had been trained in Pakistan to hijack an Indian Airlines flight piloted by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s son and of course, successor in office, Rajiv Gandhi.

K. F. Rustamji, in Sinha’s telling of the story, the BSF’s Director General, persuaded Qureshi to go ahead with the hijacking plot, but as an Indian intelligence agent. So, according to Sinha’s version of events, Qureshi was to hijack a flight from Srinagar and then “create the impression that he was a member of the al-Fatah and was hijacking the plane for liberating Kashmir from India”. To ensure that Pakistan became enmeshed in the affair, Qureshi was told he should refuse to hand over the possession of the plane to the airport authorities unless Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, then the leader of the opposition in Pakistan, came to see him.

After the meeting with Bhutto, he would release the passengers and blow up the plane. Okay, this is a story. Let’s look at it.

An obvious flaw in this account by Sinha stands out. From the eyewitness testimony of K. H. Khurshid, the former president of Pakistan-administered Kashmir, remember, it wasn’t Qureshi who wanted the plane blown up. In fact, he seemed to want quite the opposite, just to dent it a little.

Writing a decade after Sinha, the British historian Alastair Lamb arrived at much the same conclusion. “The Pakistani authorities”, he claimed, “were extremely suspicious of the motives behind the hijacking, though public opinion obliged them to act with considerable circumspection”. Among the reasons for the Pakistani suspicions, according to Lamb, was that the hijackers were “armed with toy weapons”, that many of “the passengers were either Indian service personnel in disguise or their families”, and that the Fokker friendship was the oldest of its type in the Indian Airlines fleet and thus could be “expended”.

Lamb asserted, a bit like Sinha, that while Qureshi had indeed been a genuine National Liberation Front operative, he was recruited by the BSF in July 1970. Then he ”became involved in the scheme to hijack an Indian aircraft being considered by Indian intelligence in Srinagar, where it was seen to be ‘a disinformation operation’ of great promise”. That’s all Alastair Lamb.

Beyond claiming that his version of events was endorsed by Lahore police authorities, however, Lamb provides no evidence in support of his assertions. Again, like Sinha’s story, many of Lamb’s claims do not seem to me to stand the test of reason. Fake weapons have frequently been used by hijackers.

There was a famous case in Kolkata, where a Burmese hijacker hijacked a Thai Airways plane to Kolkata with nothing but a bar of soap with wires sticking out of it. Indeed, it is possible to argue that if the Qureshis actually had the patronage of India’s covert services, they would have had no trouble getting real weapons and transporting them past airport security. Since civilian aircraft are covered by insurance many more, there is no particular reason why India should have found one airplane more expendable to than another.

Hashim Qureshi’s memoirs, unsurprisingly, challenge Lamb’s rendition of events in no uncertain terms. In his own defense, Qureshi suggests that the historian ignored critical evidence which emerged during the hearings of the judicial inquiry into the hijacking.

Qureshi’s memoirs contain very detailed accounts from the special court’s hearings, notably the critical testimony of a Major Rahim Shah. Major Shah stated that he was denied permission to disarm the hijackers even after the passengers had been released and critically that the orders were not revised even after it turned out that the weapons the Qureshis were carrying were fake.

Someone wanted them on the tarmac brandishing their weapons for the cameras. This would suggest that high-level officials in Lahore were shaping the course of events rather than some Indian spies sitting several hundred kilometers away.

All the conspiracy theories, moreover, trip on the central question. What motive would India have had to carry out the hijacking of its own plane? Lamb and Sinha both say India used the hijacking as a pretext to cut off transport through its airspace between East and West Pakistan, thus preparing the ground for the 1971 war. The problem is that Pakistan’s overflight rights had already been restricted since 1965 for military flights.

Had India chosen, it could have denied permission for flights irrespective of the hijacking. Furthermore, while the suspension of air communications might indeed have created some logistical delays for Pakistan, western and India media reports from the time make clear that Pakistan’s C-130 transport aircraft were able to supply East Pakistan through Sri Lanka, which just added a few hours to the flight.

Credible accounts by Pakistani military personnel also assert that the embargo did not hinder the flying in and out of personnel as the East Pakistan situation deteriorated. For example, a two battalion brigade used during the notorious Operation Searchlight was airlifted into Dhaka in late February 1971. The overflight ban, critically, had no impact on maritime transport, the principal means used to logistically support Pakistani forces in the East. The most important fact is that there is no evidence to show that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi or anyone else was even considering war at the hijacking in January.

According to one of her leading biographers, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi only turned her mind to the East Pakistan issue at the end of March 1971, after being re-elected to office earlier that month. As such, it seems profoundly unlikely that Indian intelligence would have been seeking to create a climate for an air blockade and a war, which hadn’t even entered the mind of the political establishment at this stage. So, am I claiming I know the truth and that both Sinha and Lamb are completely wrong? No.

No one except those intimately involved in the affair at the highest levels can claim to, and most of them unfortunately are dead, so they can’t tell us. Maybe something will emerge from an archive one day that will settle all these debates. The point is, there is just no evidence for the false flag theory, and yet it lives on in both India and Pakistan.

The question is, why?

Kashmir’s conspiracy theories

Let’s begin with the fact that false flag theories or conspiracy theories are common. Till the 26/11 reconnaissance agent David Headley was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), many believed the massacre of Sikhs at Chittisinghpora in Kashmir was a false flag operation. This was a widely held belief.

Their case, as I have recently written, was helped by a botched police investigation which led to the acquittal of the Lashkar-e-Taiba perpetrators, as well as the killing of five innocent people who were dressed up to look like terrorists. The truth is, India’s headline management efforts at the time became the enemy of its own cause. Anyway, Headley provided first-hand testimony that the Lashkar senior commander Muzammil Bhat told him that the terrorist group had not only carried out Chittisinghpora, but had also recruited the controversially killed Ishrat Jahan as an agent to stage a terrorist strike.

Is the fact that Muzammil made this claim to Headley conclusive? No, obviously not. If seen against the Lashkar’s long history of conducting communal killings, and its stated desire to kill Indian politicians, it is at least probable and somebody making false flag claims should be asked to back up their story with evidence. The writer Arundhati Roy’s claims that the attack on parliament was a false flag operation, similarly, rest on pretty shaky ground.

She has claimed, for example, that, I quote, “based only on Afzal’s confession”—he was one of the conspirators—”the government of India recalled its ambassador from Pakistan and mobilized half a million soldiers to the Indian border.” Only on Afzal’s confession? That’s just not true though.

There are acres of court documents which detail the evidence the government relied on to convict Afzal Guru, who was later hanged for his role in the terrorist attack. Let’s say you don’t believe in those court documents because like all legal cases, there is a defense side and a prosecution side.

Well, perhaps you’ll believe Lieutenant General Javed Ashraf Qazi, the former head of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), who in 2003 told his nation on the floor of parliament, I quote, “not to be afraid of admitting that the Jaish-e-Mohammed was involved in the killing of thousands of innocent Kashmiris, bombing the Indian Parliament, Daniel Pearl’s life and the attempts on President Musharraf’s life”.

That’s what an ISI chief said. There’s all sorts of reasons why false flag claims fly. In Pakistan, many well-meaning liberals find it genuinely hard to accept that their country’s military is involved in the cynical mass killing of civilians.

A certain kind of ultra-nationalist common to both India and Pakistan, sadly, isn’t even willing to concede the possibility that their country might be wrong on anything. There are people in India who don’t like the government and, therefore, seize on false flag conspiracy theories because they’re willing to blame their rulers for almost anything. There are others, of course, who will not concede even the government’s most blatant failings.

As best as we can though, all of us, journalists, historians, citizens, need to work to unpack the elements of the stories we hear, aware of at all times that what we think is the full truth is very rarely available. It’s hard to do that and not be led away by one’s biases on contentious emotional issues. But that’s when we most need to sift fact from our feelings and try to grope our way towards the truth.

I’m Praveen Swamy and I’m a Contributing Editor to The Print. Thank you for watching this episode of The Print Explorer.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Adding grist to the mill is Prez Bill Clinton’s foreword for Madeline Albright’s 2006 book,The Mighty & the Almighty,”During my visit to India in 2000,some Hindu militants decided to vent their outrage by murdering 38 Sikhs in cold blood.” This comment of Pres Clinton is held out as proof of India’s perfidy by Pakistan and also made its way to US Congressional hearings.