New Delhi: The Yamuna River in Delhi rose to an all-time high of 208.62 metres Thursday — well beyond the ‘danger’ mark of 205.33 metres set by the Central Water Commission (CWC) — flooding parts of Delhi, from Civil Lines to Rajghat.

The Yamuna floodplains in the National Capital Territory (NCT), spanning 80.55 sq. km, have seen routine flooding for decades. A significant portion of the houses situated in these floodplains are reportedly encroachments, constructed too close to the river. Consequently, during the monsoon season, as rainfall raises the water levels, the excess water overflows onto the floodplains and adjacent low-lying areas.

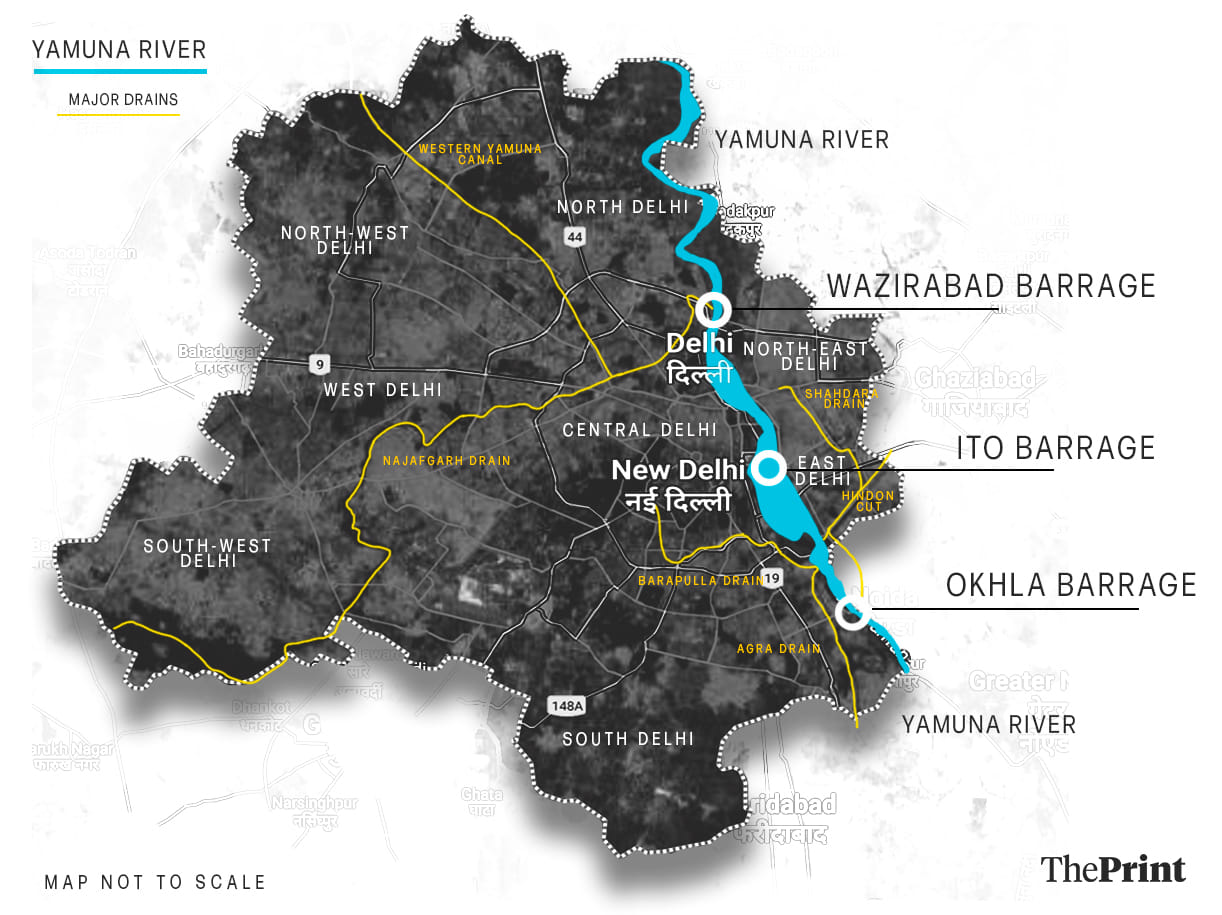

Specifically in Delhi, the risk of excessive damage by floods is compounded by two man-made factors — the presence of three mammoth barrages within a 22 km stretch of the Yamuna in the city, which restrict the river’s natural flow; and extensive construction on the floodplains, which prevents proper water retention and drainage.

Last year, too, the Yamuna had breached the danger mark.

“Yamuna is essentially a monsoon river. It gets recharged every year as the South-west monsoon sets in. This recharge is necessary for the groundwater to replenish, too. But that only happens through the floodplains. How can we recharge our groundwater if our floodplains aren’t available?” said environmentalist Vimlendu Jha to ThePrint.

But why are this year’s floods different? Unprecedented rainfall is one factor. Delhi received a cumulative rainfall of over 300 mm within two weeks of July, show media reports. According to India Meteorological Department (IMD), the mean rainfall for the whole month of July is usually 172.7 mm. However, IMD data also says that the maximum rainfall in July is spread across eight to nine days, which is what was observed this year too.

“The larger blame sits with us though,” said Jha, “for ignoring warnings by environmentalists for decades, and not preparing the city’s floodplains or drainage system for floods that were an eventuality.”

ThePrint explains why the Yamuna floods, and how decades of urban development has contributed to this yearly phenomenon.

The narrowing Yamuna

The Yamuna, which originates from the Bandarpunch peak in Uttarakhand, traverses 1,376 km across Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh to finally join the Ganga at the Sangam in Prayagraj. There are a number of barrages on this stretch.

Barrages are structures constructed on rivers to regulate the flow of the river and divert water for other purposes like irrigation. They aren’t constructed to store water in reservoirs like dams are and therefore cannot stop water indefinitely. When the water levels reach a certain limit, to avoid the risk of structural damage, the gates need to be opened to let the water out.

The Yamuna has six major barrages on it, three of which are on the 42 km stretch of its course through Delhi — the Wazirabad, ITO and Okhla barrages.

The Dakpathar and Hathnikund barrages are in the upper-catchment area of the Yamuna — situated in Dehradun and Haryana, respectively. It is after the Hathnikund barrage, in Palla village, that the river enters Delhi.

Upon entering Delhi, the river encounters the Wazirabad barrage first, from where a significant portion of the water needed for Delhi’s supply is diverted. However, the water supplied — 950 MGD (million gallons per day) — still falls short of meeting Delhi’s demand of 1,150 MGD, reportedly. It is also in this area that the Yamuna receives 80 per cent of its total pollution from the 22 drains and sewers of Delhi that open into it, show media reports.

The Yamuna’s flow in Delhi, therefore, is actively constrained. A study conducted in 2014 revealed that the Yamuna’s annual water flow is 13.9 thousand million cubic metres. After it passes the Wazirabad barrage, the flow reduces by almost 70 per cent.

And it is not just the Wazirabad barrage that causes this. Over the years, bridges and embankments along the basin have changed the Yamuna River itself. A study by the Indian Society of Remote Sensing in 2019 showed that the increase in ‘engineered structures’ decreased the active width of the Yamuna in Delhi from 10.4 km square kilometre in 1976 to 7.4 square kilometre in 2017.

With this reduction in the width of the river, it is no longer equipped for the huge flow during the seasonal flooding of the Yamuna.

Encroached floodplains

Floodplains are essentially areas around a river that are created by sediments deposited by a river’s flow. These areas act as part of the river and their natural purpose is to be inundated during excess flow.

Floodplains also absorb this excess flow of the river into the ground, thus recharging aquifers for groundwater use — which are necessary for Delhi and Haryana, since both depend on groundwater resources.

The Yamuna in Delhi thus has a unique problem. It overflows in the monsoons, and dries up in the summers, requiring the city administration to implement measures to mitigate both.

“Flood retention and groundwater recharge are two roles of the floodplain. Now if you concretise the entire area of the floodplain, neither will you be protected from floods, nor can you usefully tap the monsoon rain for groundwater recharge,” said Sushmita Sengupta, programme manager of the Water Programme at the Centre for Science and Environment, to ThePrint.

In a story published Monday, The Print had quoted a senior official of the Irrigation and Flood Department of Delhi, who said “The flooding (of the Yamuna) this time has shown that we need to re-strategise and also clear the floodplain of any encroachment. The river water has to have space to flow. The encroachments constrict the water’s route resulting in backflow and flooding.”

Structures such as the Commonwealth Games village, Akshardham temple, and multiple houses and jhuggis have all reportedly been built on the Yamuna floodplains. Even now, the DDA plans to delineate the floodplain area (Zone O) to allow regulated development on it.

Also read: Why Delhi drowned: Jammed gates of crucial ITO barrage & a Delhi-Haryana blamegame

Who is to blame?

“Right now, when the Chief Minister (Arvind Kejriwal) blames the Hathnikund barrage for the floods, you know it is unscientific. There are systemic issues at play,” said Jha, referring to the “mismanaged” storm drains in Delhi, that are responsible for carrying storm water or extra flooded water away from the city roads.

Delhi’s drainage system is still functioning on a 1976 master plan. A new plan, made by IIT Delhi in 2018, was dismissed reportedly as ‘too generic’ in nature by the Delhi government. Delhi’s drains are too old to handle the present storm water pressure, said Sengupta. “They are not designed for carrying peak intense rainfall,” she said.

A high-level committee formed by the National Green Tribunal in January 2023 was tasked with the rejuvenation of the Yamuna. It reported that as of May 2023, only 26 km of the city’s 442.63 km of drains and sewer lines have been de-silted.

“Climate change is a real issue that the city and the world at large is tackling. But blaming it for the present scenario is not right because we’re shunning the responsibility of the authorities to mitigate disasters and to learn from past mistakes,” urges Jha.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: Wide-eyed floating puppies, stranded cows—animal lovers on NDRF boats on Delhi flood rescue