New Delhi: The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), or Nuke ban treaty, came into force on 22 January 2021. It is a legally binding instrument aimed at total elimination of nuclear weapons, under the aegis of the United Nations.

The treaty, due to its very provisions, did not find much support from the P-5 countries of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) despite being party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). This is since it prevents countries from participating in any nuclear weapons-related activities, including development, testing, possession, stockpile, use, or threat of use of nuclear weapons.

India had refused to be a party to the talks, which concluded in New York on 7 July 2017, when the treaty was being negotiated at the UN. Earlier in March that year, New Delhi had abstained on this resolution and provided a detailed ‘Explanation of Vote’. Further, India expressed its position on the issue of its non-participation in these negotiations at a Plenary of the Conference on Disarmament, also held in March 2017.

However, it was due to Honduras that the treaty finally came into effect as it completed the required 50 ratifications in October 2020.

ThePrint reads through the provisions and explains why nuclear-weapon countries, including India, didn’t sign the treaty.

Also read: Why this nuclear arms race is worse than the last one

Provisions of the treaty

The treaty, which has a 24-para preamble, lists numerous prohibitions on the use of nuclear weapons, including undertakings to not develop, test, produce, acquire, possess, stockpile, use or threaten to use nuclear weapons. It also prohibits the deployment of nuclear weapons on national territory.

TPNW makes it obligatory for states to “suppress” any of the prohibited activities in its territory, compensate and provide necessary assistance to persons affected by nuclear testing in any way, and also take remedial action to undo environmental damage in areas under its jurisdiction which have been affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons.

The provisions of the treaty aren’t binding on non-signatories.

Also read: Stigmatise and shame nations that keep nukes if treaties are futile in banning them

How the treaty came to be

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) spearheaded the efforts for the signing of a nuke ban treaty and was awarded the Nobel Prize for peace in 2017.

The ICAN website claims that the treaty fills a “significant gap” in international law. While the NPT seeks to prevents countries from manufacturing nuclear weapons, it doesn’t address the use or possession of such weapons by all parties.

“The nuclear weapon ban treaty is based on the rules and principles of international humanitarian law, which stipulate that the right of parties to an armed conflict to choose methods and means of warfare is not unlimited, that weapons must be capable of distinguishing between civilians and combatants, and that weapons causing superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering are prohibited,” the ICAN website states.

The United Nations General Assembly in 2017 decided to hold a conference to negotiate a legally binding instrument to end the use of nuclear weapons.

TPNW was first negotiated in March 2017 and adopted in July 2017 with support from 122 countries — it had one vote against (The Netherlands) and one abstention (Singapore). It was opened for signatures by the UN Secretary-General in September 2017.

Also read: NPT turns 50. The first half it lived a lie, the second half it saw its own demise

Why India opposes the treaty

In its explanation of vote on the abstention, India said it wasn’t convinced that the resolution could address the longstanding expectation for a comprehensive instrument on nuclear disarmament. India also maintained that the Geneva-based conference of disarmament is the single multilateral negotiation forum.

India says it is under no obligation to the provisions of the treaty since it never supported it.

According to New Delhi, India did not intend to “be bound by any of the obligations that may arise from it. India believes that this Treaty in no way constitutes or contributes to the development of any customary international law”.

India also said that while New Delhi is committed to a nuclear-weapon-free world and supports an internationally verifiable withdrawal of global nuclear weapons, “it doesn’t think the current treaty takes into account the verification process”.

Also read: India and China increased their nuclear weapons stockpile over last year: Swedish think tank

India’s nuclear ambitions

Currently, India possesses approximately 150 nuclear weapons that it can launch from missiles and aircraft. It spent approximately $2.3 billion in building and maintaining its nuclear weapons.

In the past too, India has refrained from signing nuclear disarmament treaties such as the NPT and Comprehensive Nuclear Ban Treaty (CTBT), primarily because it feels they are discriminatory — while non-nuclear states aren’t allowed to have nuclear weapons, nuclear-weapon states have no obligation to give them up.

Also, the NPT only recognises a country as a nuclear power if tests were conducted before 1967. India isn’t ready to sign the treaty as a non-nuclear weapons state.

After the 1974 Pokhran nuclear test, India was denied nuclear technology by the West, with sanctions led by the US. This isolation and domestic support for possessing nuclear power led India to aim for complete independence in the nuclear fuel cycle, which entails all processes in generating nuclear energy — exploration, mining, fuel fabrication heavy water production, fuel reprocessing and waste management.

In 1992, the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), a multilateral export control regime, decided, as a matter of policy, to stop all nuclear commerce with countries that have not ratified all NPT safeguards. This basically made India an outcast, boosting the country’s confidence in self-reliance and reiterating the philosophy of expanding nuclear powers on its own with certain safeguards. In September 2008, the NSG exempted India though it hadn’t ratified the NPT.

While India wants to be part of the NSG, its unwillingness to sign the NPT has drawn opposition from several countries, but mainly from China, which has repeatedly blocked India’s attempts at joining the group.

In 2006, India signed a civil nuclear deal with the US, which was the first implicit recognition of India as a nuclear power. The core of this agreement was the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

In 2017, India joined the Wassenaar Arrangement, to build up a strong case for its entry into the NSG. Like the NSG, Wassenaar is a group of elite countries that subscribe to arms export control. The agreement ensures greater transparency in the exchange of conventional arms, dual-use goods, and technologies. All UNSC members are part of the agreement except China.

Prior to this, India acceded to the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) in 2016 while in 2018, it was admitted to the Australia Group.

Apart from the US, India has also signed a number of civil nuclear agreements with countries such as France, Russia and Japan, among others, even as it aims to increase its nuclear power generation capacity by over three times in 10 years.

As of January 2020, the installed nuclear power capacity in India is 6,780 megawatt (MW), which is about 1.84 per cent of the total installed capacity of 3,68,690 MW. This is the current nuclear power capacity.

Also read: Why India and China haven’t used the ‘N’ word throughout the Ladakh conflict

Opposition from other nuclear powers

Other nuclear-armed countries do not support the TPNW either, which raises questions about its effectiveness.

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) countries, which in 2016 expressed commitment to nuclear deterrence, haven’t signed the treaty either.

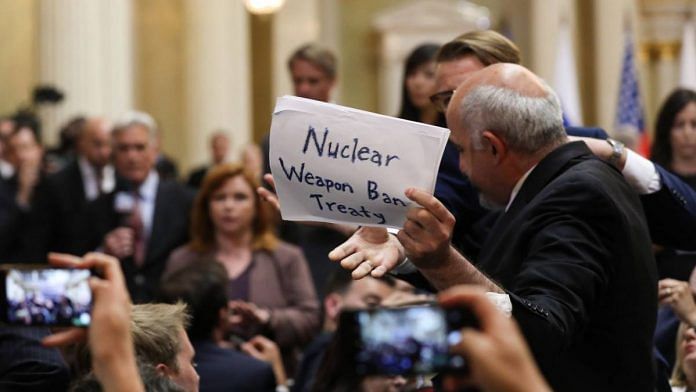

The United States, France, and the United Kingdom in 2018 led a group of 40 nations in protest against the UN talks when the treaty was being discussed. The talks were supported by more than 120 countries, and were led by Austria, Brazil, Ireland, Mexico, South Africa and Sweden.

Countries believe the nuke ban treaty undermines the importance of the non-proliferation treaty. Gustavo Zlauvinen, president-designate of the 2020 Review Conference for the NPT has raised questions about the effectiveness of the TPNW, saying that it cannot challenge the “legitimacy of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty”.

The US, though, said it believes in the NPT and reduced its nuclear weapons by 85 per cent since. In a letter to the signatory countries of the treaty, it said the five permanent members of the UNSC — also recognised as nuclear-weapon states by NPT — stand united on their opposition to the potential repercussions of the treaty, which they termed a strategic miscalculation.

One major contention was the possession of nuclear weapons with North Korea, and the US argued that while disarmament could be possible in the future, it wasn’t possible at the time the treaty was being discussed. The letter went on to add that it “turns back the clock on verification and disarmament, and is dangerous” to the NPT.

Also read: Don’t ignore the nuclear option just because it’s controversial

The cardinal objective of disarmament can only be achieved as a cooperative and universally agreed undertaking, through a consensus-based process involving all the relevant stakeholders, which results in equal and undiminished security for all States. It is indispensable for any initiative on nuclear disarmament to take into account the vital security considerations of each and every State.