Bengaluru: The Tamil Nadu and Karnataka governments have once again locked horns over the Rs 9,000-crore Mekedatu project.

Karnataka Chief Minister Yediyurappa Saturday wrote to his Tamil Nadu counterpart M.K. Stalin, urging him not to oppose the reservoir project.

“We have been fighting for Karnataka’s rights in the Cauvery basin and have been successful. This matter is also before the Supreme Court, we are putting forward our case,” Yediyurappa wrote. “We will continue our legal battle for our rights. We are confident of winning it and completing the Mekedatu project.”

Stalin wrote back Sunday saying that the Karnataka government should not to pursue the project, as the reservoir would impound the free flow of Cauvery water into Tamil Nadu.

The letters are the latest salvoes in the history of the controversial project, which is part of the wider Cauvery waters dispute, one that is older than the country itself.

ThePrint charts out the twists and turns in the issue and what experts have to say about the renewed hostilities between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka over it.

What is the Mekedatu project?

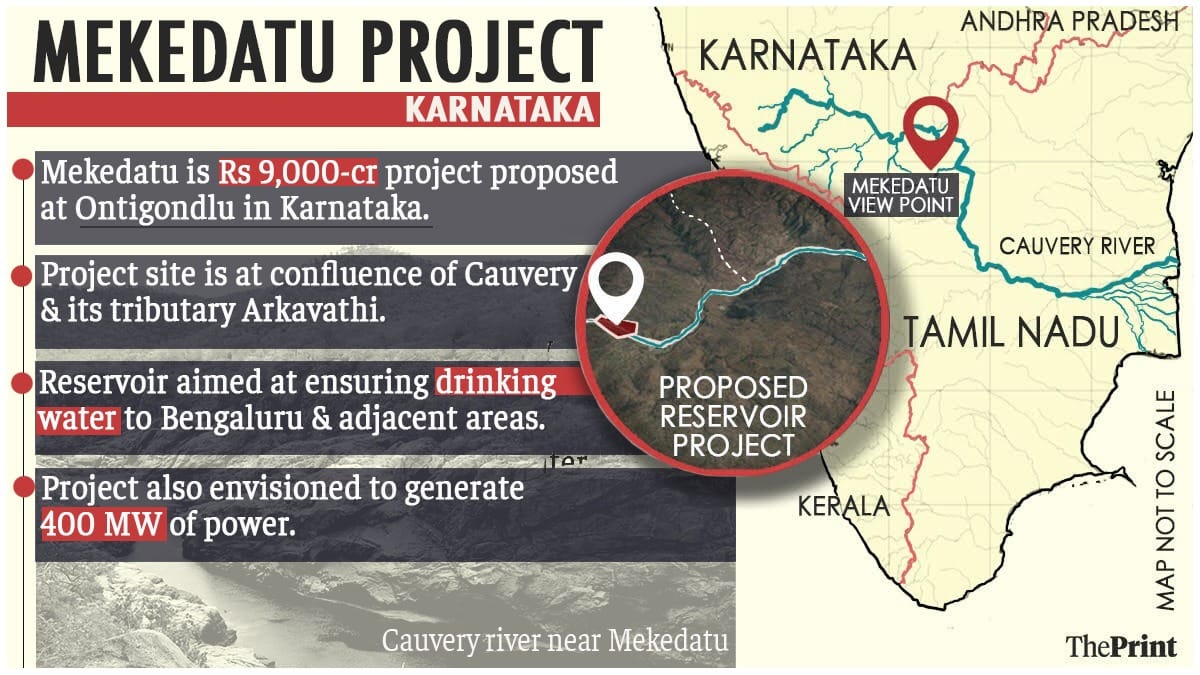

The Rs 9,000-crore reservoir project is proposed to be built at a deep gorge situated at the confluence of the Cauvery river and its tributary Arkavathi, at Ontigondlu in Karnataka’s Ramanagara district.

The reservoir would have a capacity of around 67,000 million cubic feet (tmcft) of water and is aimed at ensuring drinking water to Bengaluru and neighbouring areas. The project is also envisioned to generate 400 MW power once it is completed.

According to the ‘Pre-feasibility report of Mekedatu Balancing Reservoir and Drinking Water Project’ by Karnataka’s Cauvery Neeravari Nigam Limited, “the possibility of developing power from the Mekedatu project has been under examination since 1948”.

“However, this project was not taken up for investigation till the reorganisation of the States in the year 1956,” the report states.

The project spurred discussion in the early 1960s but was forgotten after the states locked horns over the issue of sharing the Cauvery river waters.

The issue of the reservoir, according to the report, was intermittently brought up in rounds of discussions between the state governments since 1996-1997.

Janakarajan, a professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies, however, said that since the water has to be pumped, there are doubts whether it would have been a big project back in the years when it is claimed to have been examined.

The recent version of the project, he said, was only proposed in 2013, when the project was announced by then Karnataka Law Minister T.B. Jayachandra.

The project received an in-principle nod by the then Chief Minister Siddaramaiah-led Karnataka Cabinet, following which a pre-feasibility report was submitted to the Central Water Commission by the state government.

Through this time since 2013, the Tamil government under various chief ministers had launched staunch opposition against the “unilateral actions of Karnataka”.

Tracing the long, complicated legal history of the case, Janakarajan said, “The dispute is becoming bitterer and bitterer by the day. There was a tribunal, there was a final award, there was a Supreme Court verdict and then constitution of Cauvery Water Management Board, with all the matters remaining uncertain.”

What experts say

Experts ThePrint spoke to questioned the need for the project and indicated that it might be in violation of a Supreme Court verdict in 2018.

“It’s a complex situation from Karnataka’s point of view; below the KRS (Krishna Raja Sagar) dam and the Kabini reservoir, this is the last catchment that is unregulated. Therefore the rainwater flows into Tamil Nadu without any control,” explained S. Vishwanath, an urban planner and water conservation expert.

Karnataka, he said, also hopes to control the runoff from the field as well as build a dedicated water source for Bengaluru.

Tamil Nadu, however, fears that if Karnataka controls the water all the way up to Ontigondlu, the latter might not stick to its obligation mandated by the Supreme Court.

In February 2018, the Supreme Court in its verdict on the long-standing legal conflict, came up with a water-sharing formula between the states.

“But neither party is talking about the ecological integrity of the rivers. If they had spoken about it, if they focused on that, then this necessity of Mekedatu may not be there,” Vishwanath said.

“The reservoir can be made only with the permission of the riparian states concerned, whereas now, they have not consulted anybody… Although they (Karnataka) are saying that they are constructing a balancing reservoir only to facilitate water supply to Tamil Nadu, it is not a right claim,” Janakarajan said. “Once you construct a dam, to the extent of 65 tmcft, where is the flow to Tamil Nadu.”

Conservationists and activists have also opposed the project given its impact on the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary, in which Ontigondlu falls.

Cauvery dispute

The Mekedatu is one issue in the Cauvery water sharing dispute, which has been a bone of contention between the two since 1892.

Problems between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, however, began cropping up in 1956. According to Karnataka, the 1924 agreement drawn up under British rule, between the then Madras Presidency and the Mysore Kingdom, was valid for only 50 years. The state then went on to build four dams along the river.

This prompted Tamil Nadu to approach the Supreme Court, following which the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal (CWDT) was constituted on the apex court’s directions in 1990.

The tribunal’s interim order in 1991, directing Karnataka to ensure that 205 tmcft water reach Tamil Nadu, spurred riots and was rejected by the upper riparian state. The SC, however, upheld the tribunal’s order.

Some 16 years later in 2007, the tribunal came up with its final award, allocating 419 tmcft of water to Tamil Nadu, 270 tmcft to Karnataka, 30 tmcft to Kerala and 7 tmcft to Puducherry.

During the years with scant rainfall, the allocation for Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Puducherry will be reduced. The two states have since sparred over the sharing of water during these distress years, which at times has escalated to violence.

The apex court delivered its final verdict in 2018, increasing the allocation share to Karnataka. According to the final verdict, Karnataka would get 284.75 tmcft of water, Tamil Nadu 404.25 tmcft, Kerala 30 tmcft, Pondicherry 7 tmcft, and 14 tmcft would be reserve for “environmental protection” and “wastage into the sea”.

(Edited by Arun Prashanth)

Also read: This round to dislodge Karnataka CM Yediyurappa fails, but dissidents not ready to bow