Bengaluru: In the last one month, a few countries have recalled the widely-used heartburn drug Ranitidine, after cancer-causing chemical NDMA (N-Nitrosodimethylamine) was found in it. However, the responses to the finding have been highly variable.

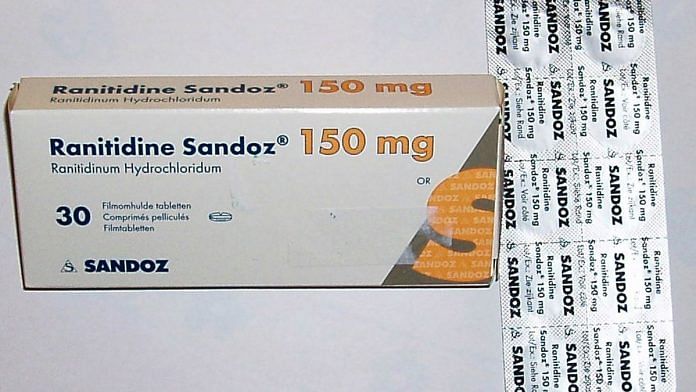

While the French and Canadian regulators have recalled the drug, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and India’s Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) haven’t. Similarly, while some major manufacturers such as GSK and Sandoz Inc. have voluntarily pulled their stocks globally, other manufacturers continue to sell the drug.

Even among companies that have recalled their products, not all Ranitidine tablets have been taken off shelves. For example, GSK has only recalled Ranitidine made from the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from one of its suppliers, namely Saraca Laboratories Ltd. However, Ranitidine made from GSK’s other API supplier, SMS Lifesciences India Ltd., continues to be sold.

Also read: GSK Pharma halts supply of top-selling acidity drug Zinetac over ‘cancer-causing’ substance

Why are companies and drug regulators reacting so differently to the issue?

One reason is that some drug regulators, like the FDA, are still looking to identify the source of the impurity in the drug, while others like Health Canada have taken the stance that Ranitidine itself is the source.

“Current evidence suggests that NDMA may be present in Ranitidine, regardless of the manufacturer,” the agency said in a recent press release. This stance is echoed by Valisure, the American pharmacy that first flagged the NDMA problem.

According to David Light, Valisure’s CEO, Ranitidine is an inherently unstable drug, and breaks down easily to form NDMA. This means the problem is unlikely to be limited to specific manufacturers or manufacturing processes, and afflicts all Ranitidine in the market.

“The only way to fix the drug is a complete recall,” Light told ThePrint in a phone interview, “There is no way to fix the drug, the drug itself is the problem.”

Read on to understand more about the differing stances.

What is NDMA?

NDMA is a chemical found in many foods like smoked meat, milk, beer and cereals. There is plenty of evidence that it causes cancer — it consistently causes tumours in rodent studies, while human studies show a link with gastric, oesophageal and bladder cancers, among others. People consume low levels of NDMA all the time through air, water and food.

A study from Kashmir, published in 1988, found 1,010 nanograms (ng) of the chemical in every kg of smoked fish sold in the local markets. Meanwhile, a 2002 WHO report, based mainly on Canadian data, estimated that daily exposure for the general population couldn’t exceed 8 ng per kilogram of bodyweight per day. This means that a person weighing 60 kilograms would be exposed to 480 ng of NDMA in a day.

While NDMA has been on the radar of health experts for a long time, it made global headlines last year when several countries found high levels of the carcinogen in a class of blood-pressure drugs called sartans. Eventually, the contamination was traced to a Chinese API manufacturer (an API or active pharmaceutical ingredient is the raw material for a drug) called Zhejiang Huahai. Huahai had reportedly altered its manufacturing process for the API of valsartan in 2011, to cut costs and improve efficiency. But an unexpected side-effect of new ingredients it was using was the production of NDMA. In other words, NDMA was a contaminant arising from the manufacturing process — it is possible to make valsartan without creating NDMA, as many manufacturers did until 2011.

Around the time the sartan fiasco occurred, the FDA established a safety limit for NDMA in pharmaceuticals, at 96 ng per day. If manufacturers stick to this cap, the risk to an individual would be very low; the FDA estimates that for every 100,000 people consuming this much NDMA through medicines each day for 70 years, there will be less than 1 extra case of cancer.

Also read: After US red-flag, Modi govt asks states to check samples of acidity drug for cancer agent

Why has NDMA turned up in Ranitidine now?

Ranitidine has been around for close to 40 years now. But no one really looked for NDMA in it using methods designed to detect the carcinogen, Valisure says. Further, a few million nanograms may be high enough to cause cancer with long-term exposure, but are not enough to cause acute symptoms like vomiting and headache — something that would have shown up in drug adverse-effect reporting systems. This situation changed after the sartan episode, which prompted Valisure to look for NDMA in various commonly used drugs. They began looking for NDMA in multiple brands of Ranitidine using an FDA-prescribed gas-chromatography method that required the drug to be heated to 130°C. (Gas-chromatography is a way of separating the components of a drug after vapourising it.)

This is when they found NDMA levels as high as 3 million nanograms per tablet of Ranitidine. Suspecting that the high levels might be because the drug was breaking down at 130°C, Valisure then designed another method to more closely mimic what happens to the drug in the human body. In this new method, Valisure’s scientists exposed Ranitidine to gastric fluids, sodium nitrite commonly present in the stomach, and a normal body temperature of 37°C. Yet again, they found NDMA levels in the millions — far above the 96 ng limit by the FDA. This meant that even though NDMA may not be present in Ranitidine tablets, it is very likely to be formed once it enters a person’s body.

This led the pharmacy to file a petition to the FDA on September 9, requesting that the regulator recall all Ranitidine products from the American market. One of the key bits of evidence cited in the petition is a 2016 Stanford University study. Here, the study investigators gave 10 participants a tablet of Ranitidine each, and measured NDMA levels in their urine for upto a day before and after. They found that NDMA levels spiked as much as 400 times to 47,000 ng after the drug was taken.

Given that the amount of NDMA excreted in urine is less than a percent of what is absorbed by the body, the Stanford study participants were likely exposed to levels similar those found in the Valisure study – a few million nanograms.

Also read: Popular acidity drug has cancer-causing substance, says US health regulator

Is NDMA a by-product of the manufacturing process, like it was with valsartan?

According to Light, it most certainly isn’t. He argues that his team wouldn’t have detected millions of nanograms of NDMA in the gas-chromatography test, if it wasn’t the Ranitidine molecule itself that was breaking down to form the carcinogen. The molecule has all the raw materials needed for this reaction – nitrite at one end and dimethylamine at the other. Throw them both together, and NDMA can easily result.

“The fundamental problem here is that the drug itself is unstable. It’s not a manufacturing issue. It’s actually an issue of the drug falling apart,” says Light.

However, in response to an emailed questionnaire from ThePrint, an FDA spokesperson said, “The FDA does not know the source of NDMA in Ranitidine at this time. This is an ongoing investigation.”

Emailed questions to the Drug Controller General of India went unanswered.

If Ranitidine is the problem, shouldn’t all manufacturers recall it?

Light argues that this is the case: “It doesn’t matter where it was made, or how it was made. All products containing the drug are fundamentally unstable. And there’s extremely strong evidence that it will form very high levels of NDMA in the human body.”

Yet, neither all regulators, nor all manufacturers are finding the high levels expected. In a September 13 press release, the FDA said that its preliminary tests had revealed NDMA levels that “barely exceed amounts you might expect to find in common foods”. Meanwhile, Milind Joshi, president, global regulatory management at JB Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Ltd, a major Ranitidine manufacturer in India, also told ThePrint that the company’s preliminary tests revealed very low levels of NDMA.

Also read: India again lobbies with Beijing to sell its generic medicines amid US-China trade war

This isn’t unexpected, says Light. The FDA has been testing Ranitidine samples this year using a new liquid chromatography method, which may or may not break down the drug like the human body does. The agency developed this method after it became evident that its previous gas-chromatography method (which Valisure had originally used) was producing high levels of NDMA at 130°C. The problem is that the FDA’s new method doesn’t mimic the human body, says Light. For any test to reliably estimate the risk to humans, it must simulate stomach conditions, like the method designed by Valisure did, he argues.

If Light’s reasoning is correct, it could explain why regulators are finding widely varying levels of Ranitidine. Fresh batches, tested immediately after manufacturing, may not have degraded yet. On the other hand, batches of drugs that have been sitting on pharmacy shelves for months may have degraded due to heat, light and other agents.

Sure enough, some regulators are finding high levels of NDMA, unlike the FDA. A South Korean media report said the country’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety had tested Ranitidine from six companies, finding the lowest level of NDMA among them to be 2800 ng. However, the report didn’t specify the methods used.

What’s the solution?

If Ranitidine is the problem, the only way out to is permanently remove the product from all markets, argues Light. This is particularly important because Ranitidine is currently given to even babies and pregnant woman, for whom NDMA could be exceptionally dangerous. Replacing Ranitidine shouldn’t be impossible, given that there are multiple other safe alternatives, such as proton pump inhibitors, in the market.

If and when such a global drug recall happens, it will be extremely important to dispose of the massive stocks of Ranitidine responsibly. Previous studies have shown that Ranitidine discarded by human beings into wastewater can react with chlorine in disinfecting agents to create NDMA. If worries about drug safety are going to result in large numbers of people discarding Ranitidine, “it literally needs to be treated as toxic waste,” says Light.

Priyanka Pulla is a Bengaluru-based journalist