The temple town of Radha and Krishna embraced S Hasan when he moved to Mathura six decades ago. It would light up on both Janmashtami and Eid. Muslims would share sewaiyan with Hindus near the historic Shahi Idgah mosque.

Today, the area around the mosque is like a heavily guarded fortress. The narrow lane leading to the mosque fills up with the clap-tap of police boots and the anxious whispers about the recent Mathura court order asking for an inspection of the grounds in response to a Hindu petition on Krishna Janmabhoomi.

The Mathura that Hassan fell in love with is now the new temple-mosque powder keg, after Ayodhya and Varanasi. In the last two years, the tranquility in the town is beginning to ebb. Fifteen cases have been filed in the lower courts of Mathura, claiming that the land on which the Shahi Idgah mosque stands belongs to the Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi Trust, the managing body looking after the affairs of the Lord Krishna temple.

A ripple effect of the communal flare-up in Ayodhya after the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992 brought armed guards to Shahi Idgah mosque as well as the Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi temple. The free movement of worshippers inside the mosque and the temple complexes got fenced and the wall dividing the two structures grew taller.

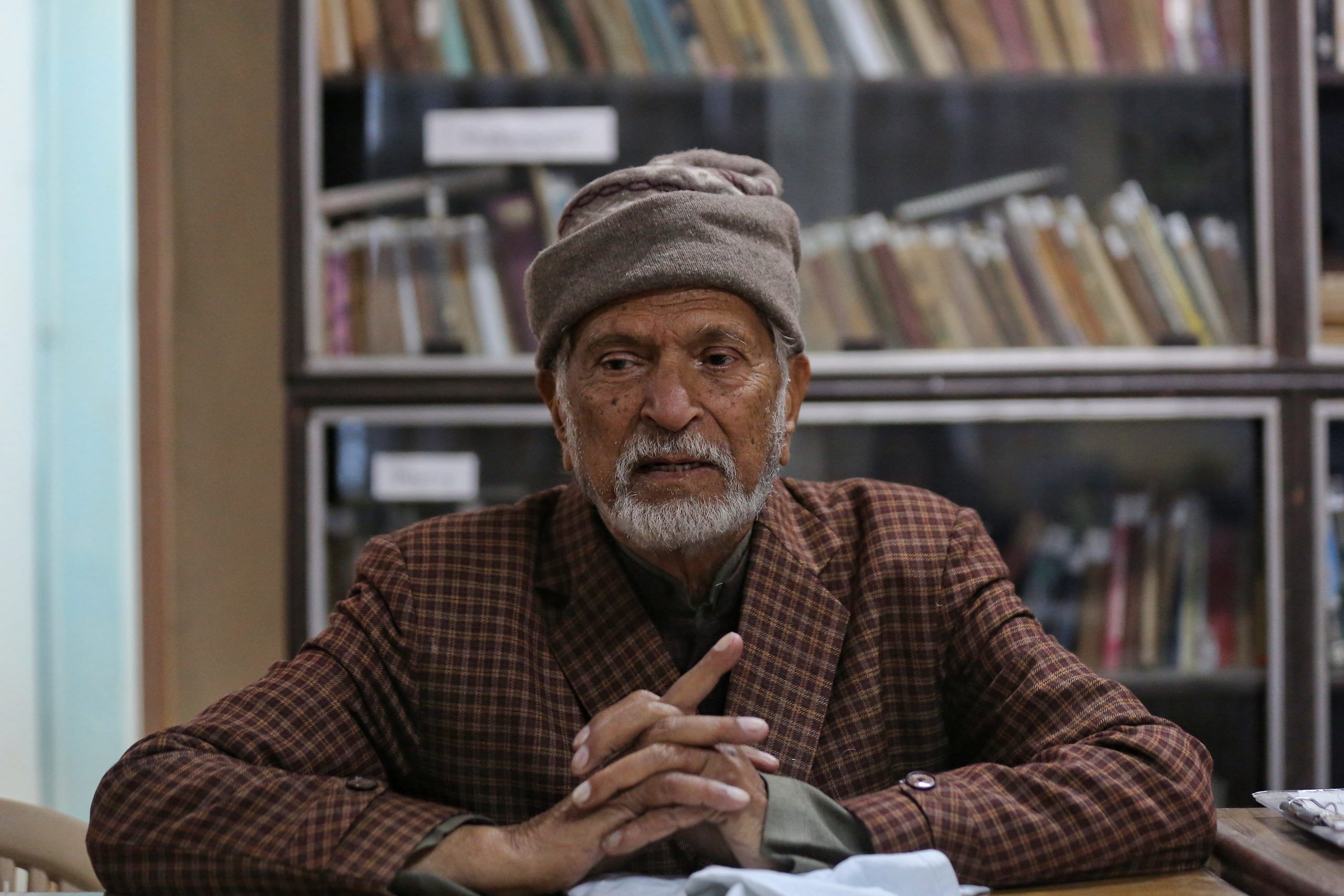

“On a barren land behind the Shahi Idgah mosque, the magnificent Lord Krishna temple came up in front of his eyes. Mathura truly became a holy city, with the mosque and the temple standing together as symbols of inter-faith unity,” says 86-year-old Hasan, a retired professor.

The Muslims fear that the change in the status quo of the mosque will bring communal tensions, especially as the inspection begins in January. The Hindus are cheering the order, calling it a step forward to get justice against historical wrongs.

“Every follower of sanatan dharma believes that the land on which the Shahi Idgah mosque stands is the main land of Krishna’s birth. They want a grand Krishna temple constructed on its place, just the way it was mentioned in history,” says Kapil Sharma, secretary of the temple trust and Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi Sewa Sansthan.

Also read: Aibak, Akbar, Aurangzeb—the Gyanvapi divide & why a controversial mosque has a Sanskrit name

1992: the year the wall grew taller

The divisions were non-existent before the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992. Anyone could go across the wall between the temple or the mosque, say residents. Today, the Hindus say the wall has to be torn down in order to access the ‘real’ birthplace, the garbhagriha (or sanctum sanctorum).

Krishna devotees have “radhe” smeared in shades of saffron on their cheeks and foreheads. Policemen in pairs stroll in the lanes, merging with the crowd, keeping a tight vigil. The mosque entry has heavy rusting metal gates, unlike the painted murals and decorated ones at the temple.

Now that the case has got new fuel with the inspection that will begin sometime in January, Mathura is likely to move to the centre of BJP’s electoral rhetoric. And the tension of what is imminent is palpable. Residents expect more security deployment once the inspection begins. The grand temple at Ayodhya is getting ready, and the Gyanvapi mosque at Varanasi already got dwarfed this year by the Kashi Vishwanath temple redevelopment. Just like a mysterious petition revived the Gyanvapi issue by allowing a survey of the mosque, Mathura too has galvanised the court route.

In April, a court-appointed team conducted videography of the Gyanvapi mosque. The Muslims in Mathura, meanwhile, see the flurry of court cases an attempt by the Hindu political parties to see a repeat of Varanasi and stir new controversies to stay relevant. The heated Gyanvapi exchanges between Hindu and Muslim leaders led to a blasphemy case against BJP spokeswoman Nupur Sharma and beheading of an Udaipur tailor.

“The Babri Masjid matter has been settled and there is no other matter for them (Hindu parties). They are creating a ground for hatred and for political gains,” says Tanveer Ahmed, secretary, Shahi Idgah Mosque Committee.

Also read: Who is Mehek Maheshwari, MP lawyer waging battle against mosque at ‘Lord Krishna birthplace’

Claims and evidence

The wary stares and hushed emptiness on the streets around the mosque contrasts with the noisy, colourful market that lines the entry of the Krishna temple nearby.

“Since the news of the court inspection has broken (on 24 December), this is the only thing that is being discussed by the Muslims here,” says Naeem Qureshi, who runs a mechanic shop close to the mosque.

The pitch in Mathura to demand a “bhavya Krishna temple” has been growing louder since the 2019 Babri Masjid judgment. Senior BJP leaders, including chief minister Yogi Adityanath and deputy UP chief minister Keshav Prasad Maurya, have made statements declaring a temple in Mathura a reality soon.

“The work for the bhavya temple in Ayodhya is going on. How can Mathura and Vrindavan be left behind? The work is progressing there as well,” Yogi had said in December last year.

But in BJP’s political history, Mathura made an appearance long before Ayodhya.

“The RSS archives show that though they were aware of the Ayodhya case, they were interested in this (Mathura) case. Ayodhya was a complicated region in the 50s and 60s, dominated by the communists and the socialists,” says Hilal Ahmed, historian of political Islam.

The RSS passed a resolution in 1959 that the Krishna Janmabhoomi along with Kashi-Vishwanath are important symbols of Hindu identity and should be given back to the Hindus for regular prayers. But the long battle in the Supreme Court for Ayodhya, in fact, gave them the mandate to reopen controversial cases, such as Shahi Idgah-Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi. In the early 1990s, the Hindu groups’ rallying cry was to demand the three sites – Ayodhya, Varanasi, Mathura – in return for 3,000 similar temple-mosque sites. Arun Shourie wrote a book listing these sites too.

Also read: Lakshmi, Sita, Rekha, Manju, Rakhi — meet the 5 women at the centre of Gyanvapi petition

The mosque history

The Shahi Idgah mosque is believed to be built by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb between 1669-70. The Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi Trust was formed in 1951 and it took them 17 years, between 1965 and 1982, to construct the Lord Krishna temple that stands today.

The Hindus believe that the Lord Krishna temple was first built by Krishna’s great grandson Vajranabh and later by the king of Orchha, Vir Singh Dev Bundela, among others. The temples were looted and demolished many times in multiple attacks by the Mughal kings. The last temple, according to the Hindus, was brought down by Aurangzeb and he built the Shahi Idgah mosque on its rubble, hiding the real garbagriha, or the basement where Krishna was born under.

“History tells us that the temple here was build four times and broken four times. The temple was grand. It was Mughals’ way to break the temple and build a masjid on it so that this hurts us (Hindus) always. This was their tradition so they made the masjid from the same rubble of the temple. All this is documented,” says Gopeshwar Nath Chaturvedi, member, Shri Krishna Janmsthan Sewa Sansthan.

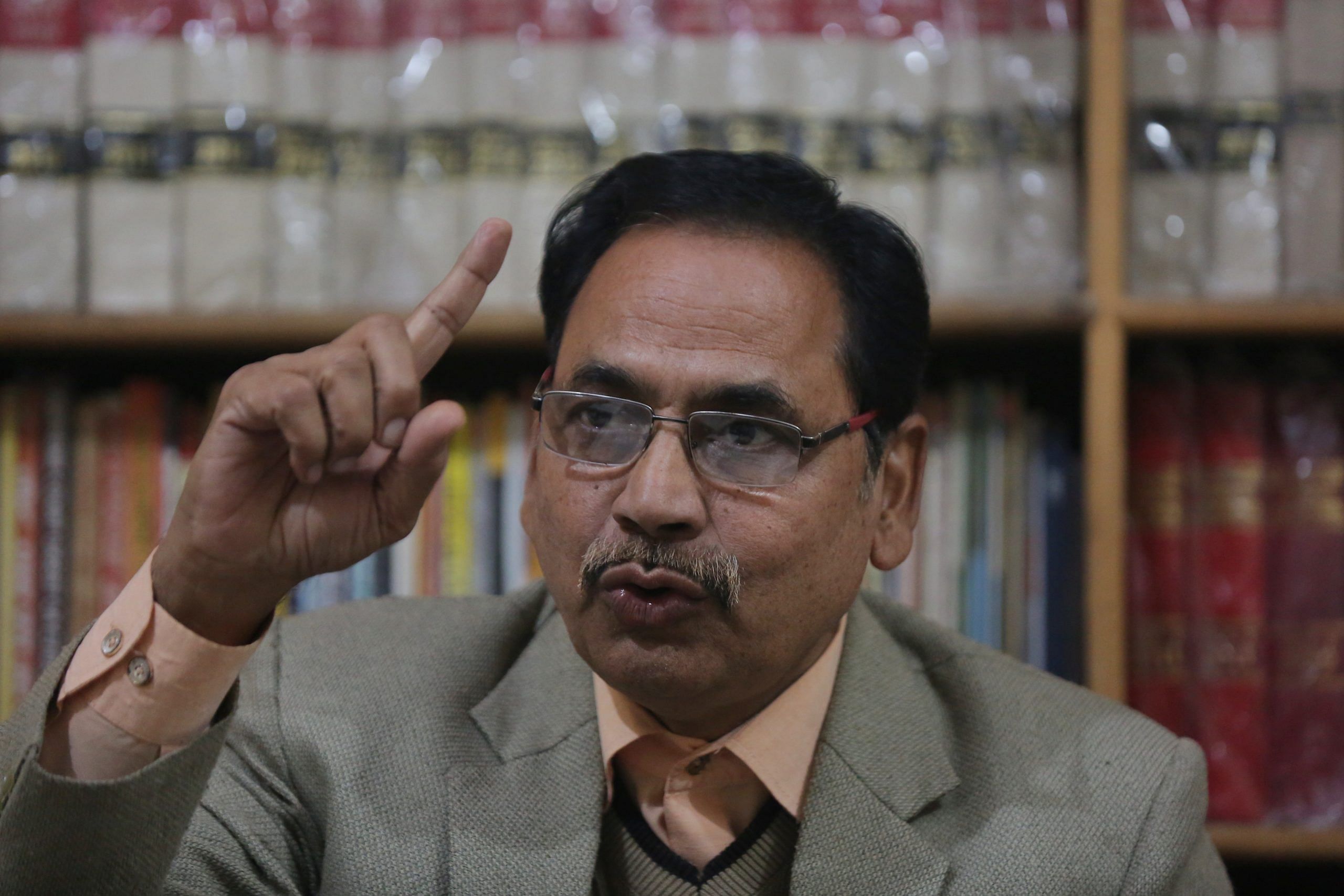

Historian Kapil Kumar explains that there are several independent accounts of the travellers of the 17th century. They describe the grand Krishna temple and how Aurangzeb razed it to the ground.

“Manuchi, an Italian who travelled to India during the period of Aurangzeb and who worked with him, writes in his account that till Jaswant Singh of Jodhpur was alive and serving Aurangzeb, the Mughal emperor never dared touch the Mathura temple,” says Kumar. After Singh was murdered, Kumar adds, Aurangzeb attacked the temple and built a mosque over it.

The applications in the court also mirror the same stories.

“In 1669, Aurangzeb built an unauthorised mosque at the same spot as Krishna’s birth place,” says the 8 December application filed by Delhi-based Vishnu Gupta, founder of Hindu Sena, a non-profit working for the upliftment of Hindus.

The petitioners and the temple sanstha members also claim that they have old records such as revenue and tax papers and utility bills that show that the entire 13.37 acre land in the area belongs to the temple.

“We have all land papers and ancient records in the name of Thakurji. The documents are almost 100 years old. We will present these as the time comes,” says Shailesh Dubey, the lawyer representing the 8 December case.

But in the case of land disputes, evidence is not the main thing, says Hilal Ahmed.

“Under the Limitation Act, if one party remains on the property for more than 12 years, then that party is legally the owner of that land. This is also applicable on religious places of worship. No matter how old an evidence one produces in the court, it all depends on who owns what. The Idgah committee has got an advantage as per this logic. They have been on this land for a long time,” says Hilal Ahmed.

Pulling out a 1929 map of Mathura city, when it was called Muttra, advocate Tanveer Ahmed who is representing the mosque in court, disagrees.

“The map shows that there was nothing but open fields next to the mosque. Both religious places are separate. Their entries are separate. A bhavya temple is made already. There is no garbagriha under the mosque. The garbagriha is already open in the temple and prayers are held there. If they are saying that garbagriha is under the mosque, then which one is this (the one in the temple)?” he asks.

Besides, most of the 15 cases are filed by people residing outside Mathura, with identical demands. Five of these cases have been rejected and in none of the cases any documentary evidence is submitted in the court, he says.

“They are saying that all of 13.37-acre land is the temple’s. But they have not even said what the demarcation and boundaries of that land are. The revenue records clearly have Shahi Masjid Idgah registered. They can verbally say anything, but they have not submitted anything in the court yet,” says Ahmed.

He also questions the right of people who have moved the court on the issue of land encroachment.

“Those who have filed the case, they are neither the owners of the 13.37-acre land, nor are they the members of the Sri Krishna Janmabhoomi Trust or the Sangh. So, what right do they have to file the cases? All these years, the temple authority never filed a case against the mosque authority on the encroachment issue,” he adds.

These outsiders, he says, are being used by the Hindu organisations to push their case for the removal of the mosque from its current spot.

“The place had always been a Hindu place. When we could not save it, it became an idgah. In morality, ethics, religion and law we have arrived to get it back,” says Alok Kumar, International Working President, VHP.

“The facts do not support the theory that Aurangzeb attacked only those persons and temples which did not accept his rule. It was not a political move. It was not to vanquish the opponents. It was his religious blindness,” says Kumar.

Also read: Will Modi govt’s minority scholarship changes hurt madrasas? Dismay, confusion & indifference in UP

Attempts to disturb peace

On 26 February last year, Mathura-based Dinesh Sharma, national treasurer of Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, a Hindu political party, filed a case in the city’s civil court calling the 1968 agreement illegal and the mosque an illegal encroachment on the temple land. The hearing in the case is ongoing.

But on 6 December, the anniversary of Babri masjid demolition, he announced that the members of the party will march to the Shahi Idgah mosque and recite Hanuman Chalisa inside the mosque complex.

The local people tell ThePrint, that the city became a fortress.

“Such a hype was created over this issue. Markets shut down and it seemed like something major will erupt. The situation became tense. The entire administration and security were out on the roads,” says Pappu Khan, who runs a mechanic shop near the mosque.

Sharma and others were arrested and later released. This year, they did it again. Sharma claims that it is his right as a Hindu to pray where, he believes, is the actual garbgreh.

“The actual birthplace of our Kanha is buried under the Idgah. We made a programme to go there as there is no court stay there. We have a right to pray. No one has prayed there for Kanha. The prayers are happening at the false garbagrih. The real garbagrih is below the mosque,” says Sharma.

Other members of the party say that they were not allowed to be present near the mosque and most of them were put under house arrest. Four of their leaders were arrested, yet, their national president changed her get up, entered the temple complex, faced the mosque and recited Hanuman Chalisa.

“She did that prayer, that is why this (inspection order) is happening. It’s God’s grace. We have crossed the first level. Rest will also be fine,” says Sharma.

The 8 December inspection order passed on the same matter, though in a different case, has only fuelled the unrest in the city.

Former MLA and leader, Congress Legislature Party of UP Assembly, Pradip Mathura claims that creating unrest through fringe Hindu groups suit the political interests of the ruling BJP. “The UP Chief Minister himself has said multiple times ‘ab Mathura ki baari hai (now Mathura)’. BJP is using religion to malign the minds of the people and to convert this controversy into votes,” he says.

Also read: Gyanvapi case reopens the politics of religion that Supreme Court had sealed shut in Ayodhya

1968 agreement and the Places of Worship Act

In 1968, an agreement was signed between the Shri Krishna Janmasthan Seva Sangh and the Shahi Idgah Masjid Trust, wherein, a part of the land belonging to the temple trust was given for the mosque.

For decades, the locals say, the city of Mathura flourished around the temple and the mosque, without this amicable agreement ever being questioned. The temple has three entry gates which are separate from the mosque’s entry. A busy road and a railway track form natural barriers between the two shrines.

Yet, in the courts, the petitioners are now revoking the validity of this agreement.

“The compromise happened with the temple sanstha but they had no authority to sign any agreements. The property involved belongs to the temple trust. We have challenged this compromise also. We are calling it null and void,” says Dubey.

Sharma narrows down the accountability even further. “The agreement was signed by one member of the sanstha, without the knowledge of other members. That member had to quit as no one agreed with the move,” he says.

He adds that the member who signed the contract must have been under pressure. This document, according to Kapil Sharma, was later not accepted by any court.

For the mosque trust, however, this document is supreme. They claim that the document is legally valid and if the temple authorities objected to the arrangement, why were they silent all these years?

According to the mosque authorities, the agreement came about to solve functional issues between the two parties. The water from the mosque used to flow on to the side of the temple, which was diverted back to the mosque. Muslim families used to stay in the ground next to the temple and there were frequent altercations with the temple authorities. So, the residents were moved from there.

“This agreement was signed for everyone’s peace. The person who signed it had the authority to do so,” claims Tanveer Ahmed, lawyer and secretary of the mosque. He says that no third party (or the current petitioners) has the right to challenge the legality of the agreement.

The mosque trust is also relying upon Section 2 of the Places of Worship (special provisions) Act 1991, which says that the religious character of a place of worship existing as on 15 August 1947 will continue. Babri Masjid case was the only exception under the Act.

But the law, writes Hilal Ahmed in The Telegraph article, can be interpreted by both the Hindus and the Muslims to present their cases. While the Muslims feel that the Act must protect the status of the mosque as their place of worship, the Hindus say that since they believe that many of the mosques were constructed after demolishing Hindu temples by the Mughal rulers, the cases need to be reopened for historical accountability.

The survey ordered this year in Gyanvapi mosque – despite the law – has boosted the confidence of the Hindu parties in such controversial matters. And the Muslims in Mathura are seeing a pattern which has come home.

“Babri masjid judgement wrote that no other mosque will be touched. But then immediately after that, there was Gyanvapi masjid and now this place,” says Hassan, who is also the president of the mosque’s trust.

The idea of protecting historical religious monuments was first proposed in December 1986 at the All India Babri Masjid Conference organised in Delhi. And it was introduced as a compromise in 1991 after thorough debates between the Hindutva groups and the Muslim elites.

Interpreted in today’s political environment, the law, however, does not give a blanket protection to the mosques, as was seen in the Gyanvapi mosque case. The religious sites protected by the ASI do not come under its purview.

Also read: For BJP, Gyanvapi is like Babri. It’ll swing elections but take India back to a dark past

Political power and the voice of the Hindu

Though Mathura case is not on the lines of a survey ordered in the Gyanvapi mosque case, the Hindu groups are seeing this as a big step forward.

“This issue is more than 100 years old. It has become more vocal now because with the change in political powers, the Hindus now feel that they can reassert themselves and that they try to reclaim their own holy places,” says Kapil Sharma.

Meanwhile, mobilising around the Shahi Idgah mosque-Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi temple issue has started quietly in UP. People fear that political heavyweights are expected to formalise groups on the lines of Ram Janmabhoomi Mukti Aandolan in Mathura as well.

The Muslim groups, however, are pinning their hopes on the judicial system. On 2 January, when the courts reopen, the mosque trust will challenge the inspection order.

But surrounded by books in the library of the school he runs, Hassan is weighed down by both the burden of history and what lies ahead. “Why should we fight in the name of religion?” he asked. “There is a mosque here and there is the temple. Why can’t we do something to make the life, the city a better place?”

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)

COMMENTS