Bulandshahr: Right outside Bulandshahr, huge, broken imperial gates signal a factory from which no smoke rises. Workers trudge into the plant and its Soviet-style buildings daily at 10 am. They sit around, discuss their problems, drink tea, wander about aimlessly, and then leave by 2 pm. On the first of every month, they check their bank accounts to see if they’ve been paid. For about a year they haven’t been. And work hasn’t materialised for even longer.

In its heyday, Bharat Immunologicals and Biologicals Corporation Limited (BIBCOL), a public sector undertaking (PSU), and its employees worked nonstop to eradicate polio from India. Today, it’s as if the facility itself is polio-stricken—stuck in a dangerous, costly paralysis.

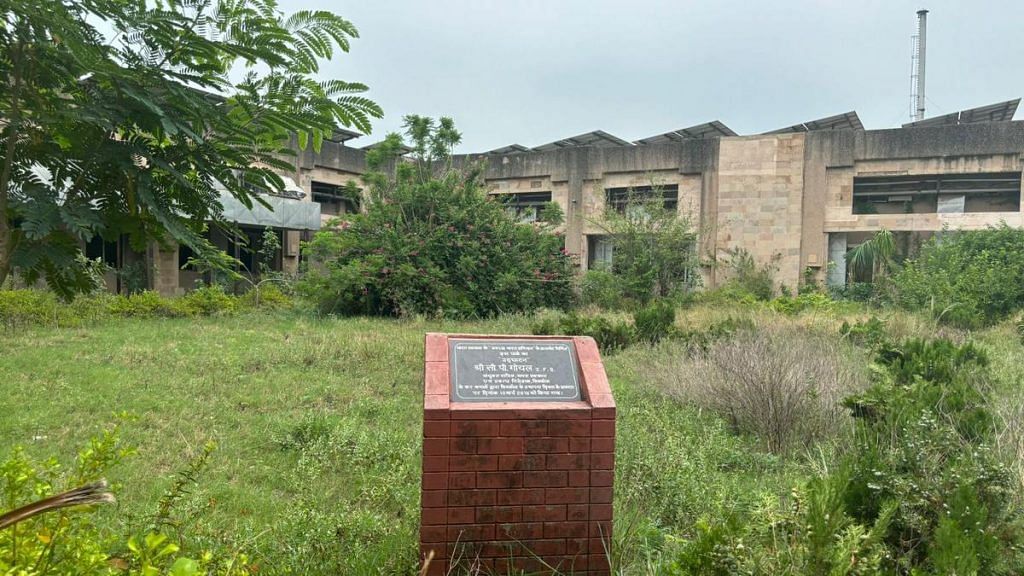

The factory, which once churned out crores of oral polio vaccines each year, is a ghost of its former self, overgrown and overrun by wild animals like nilgai. Local police constables use its lanes as running tracks. Security personnel have been disbanded, leaving the facility and all its machinery for the taking.

It hasn’t produced a single vaccine since December 2022. Workers have not been paid since August last year. And any plans to revive the plant—like a promise of using it to manufacture Covaxin in 2021—have failed.

Many of the 103 employees have been with BIBCOL for over thirty years, lured by the purpose and promise of a stable government job. Now, they are in limbo, unsure if they should look for other jobs or hold out for a revival. They suspect the facility is going to be disinvested, similar to other public sector units. All they want is for the central government to make a decision and put them out of their misery.

This has been the plight of many vaccine-making PSUs, according to a 2021 Supreme Court PIL filed by former IAS officer Amulya Ratna Nanda, the All-India Drug Action Network (AIDAN), and other petitioners. They argued the government had failed to keep its promise of reviving PSUs to make India aatmanirbhar in vaccine production. They also cited an earlier PIL that had accused the then UPA government of “willfully sabotaging” PSUs “in favour of the private pharma companies with a corrupt motive”.

Workers at BIBCOL point out two glaring missed opportunities. One was the failed Covaxin production plan. The other was the halt of polio vaccine manufacturing a year before a shortage hit India last year—with fears compounded months later when French manufacturer Sanofi shut down its plants in India. An arm of the private Serum Institute of India is now reportedly slated to ramp up production.

Desperation is mounting among BIBCOL’s workers. They have knocked on every door available to them — from their local representatives and lokpal to the Chief Justice of India and even the country’s President.

But officials at the Department of Biotechnology, under which BIBCOL falls, told ThePrint that plans are afoot to revitalise the PSU.

“There is a pursuit for revival and diversification,” said Dhananjay Tiwari, MD of BIBCOL and joint director of the department. The employees, however, are not convinced.

“This plant was dedicated to a national service. We made the country polio-free. Now what about us?” said 52-year-old factory worker Hari Om Solanki. “All the government does is mislead, misguide, make false commitments. They just want to dispose of us.”

Even now, workers come to service the machinery and ensure everything remains in working condition, even though they themselves are not working.

Also Read: Pimpri Chinchwad vs 310 women waste pickers—a 12-year battle, a trade union & Rs 7.5 cr

Crippled by inaction

Sunil Sharma, the senior plant superintendent at BIBCOL, has been fasting. It’s not for religious reasons or to lose weight. It’s practice for a hunger strike. He claims he is ready to fast unto death if that’s what it takes to get the government’s attention. Many other workers are on the same page. One says that while their bodies are alive, they’re barely living.

The glimmer of hope the workers saw in 2021 has long faded. Back then, BIBCOL was in talks to produce Covaxin with Bharat Biotech, even getting a budget of Rs 30 crore. But the proposal was simply on paper, and never took off. The workers claim BIBCOL went from making a profit of Rs 56 crore in 2015-16 to a loss of Rs 135 crore by 2021.

A senior official at the Department of biotechnology, requesting anonymity, did not confirm these figures, but acknowledged that BIBCOL had not been a profit-making company for years.

Once a symbol of modern, self-reliant India, BIBCOL’s legacy now lies in ruins among weeds, broken windows, and dilapidated Soviet-style buildings. It used to have the only helipad in the region, ready to deliver vaccines to those in need.

Set up in March 1989 with Russian assistance under Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, BIBCOL once led the charge against polio as India’s only public sector manufacturer of polio vaccines. It produced about 60 per cent of the country’s polio vaccines, with a capacity of 150 crore doses a year. It also expanded to producing medications for cholera, diarrhoea, anaemia, and measles, other than ORS, zinc tablets, and vitamin C tablets.

It’s still a functional facility that can produce any vaccine, we just need the right management and the right budget… This is an institution that can serve any government — it’s in service to the nation. It can turn into anything

-Hemant Kaushik, BIBCOL employee

But today, everything has come to a grinding halt. The workers blame mismanagement and corruption, detailing all their allegations in letters to everyone from local MP Dr Mahesh Sharma to Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud.

Hemant Kaushik, who has worked in the plant’s financial and accounting department for 32 years, alleged that three years ago, the numbers didn’t add up during an audit. This led to them realising that corrupt officials were siphoning off money. It set off a series of events—three workers were allegedly let go for and the rest were spurred to unionise and raise alarms about BIBCOL’s decline.

“BIBCOL’s workers have worked day in and day out to meet our orders. But those at the top didn’t do their job properly, which is why we’re in this position,” said Kaushik. “Others have benefitted from the plant. But the plant has suffered.”

The languishing of prime government property also angers the workers. The facility spans 64 acres and is about 20 km from the upcoming Noida International Airport in Jewar. Despite its disuse, the workers say the space still holds value.

“This is an institution that can serve any government — it’s in service to the nation. It can turn into anything,” said Kaushik, pacing up and down the path outside the facility’s central AC plant.

“It’s a common byproduct of liberalisation — the public sector is no longer fashionable… After India was declared polio-free, it looks like the government feels there’s no need for indigenous production in spite of good manufacturing facilities.”

-Madhavi Yennapu, a scientist, National Institute of Science Technology and Development Studies

Inside, all the machinery is intact. The facility still houses everything from a water treatment plant to power substations and an animal house where vaccines were once tested on monkeys. Even now, workers come to service the machinery and ensure everything remains in working condition, even though they themselves are not working. The bathrooms, however, are unusable—while cleaners are still on site, they have no money for cleaning supplies.

For the local community, BIBCOL is important for one reason: if there’s a fire in the area, the water to put it out will come from the facility’s pump house.

But the decision to keep the plant running and paying for its electricity, while neglecting workers’ salaries, has created resentment. The MD’s car, still on the site, was even being used as a local taxi by an employee— charging the government for fuel expenditure.

The last wages the employees were paid, they claim, was in January 2024, for a period of work between May and July 2023. They can’t even file their income tax for the past year. Almost all of them have taken loans from banks, and are barely surviving.

One employee, 37-year-old Gaurav Kumar, has three cases filed against him by banks. He took three loans from two banks, using his BIBCOL job as guarantee, but the bills have racked up. One private bank has filed a criminal case against him for nonpayment of loans.

“It feels like the government has washed their hands off of us,” said an angry Kumar. “I’m a normal government employee. If the court holds me criminally liable, what do I do?”

The Department of Biotechnology has already submitted a proposal for a renewal package to the Ministry of Science and Technology. Though still at the drawing board stage, the department is hopeful for BIBCOL’s revival.

A sector-wise slump

Hemant Kaushik is a familiar face at the Department of Biotechnology. He knows everyone by name and by sight, regularly making the trip from Bulandshahr to Delhi to get the department to do something about BIBCOL.

“The later the revival, the greater the liability,” he sighed. Kaushik spent an entire day in Delhi on the day Parliament was sworn in, trying to raise BIBCOL’s plight with India’s new crop of MPs.

While Kaushik and his colleagues aver that the government has written them off as radicalised troublemakers, the Naxalites of the PSU sector, department officials maintain that they are keen on revitalising the plant.

But deciding what to do with PSUs past their prime is a problem the central government has been grappling with for decades. In 2010, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare, led by former health secretary Javed Chaudhary, submitted a report on the licences of three major PSUs being suspended for not following good manufacturing processes and suggested a roadmap for their revival.

Subsequently, the licences of the three PSUs—Central Research Institute in Kasauli, Pasteur Institute of India in Coonoor, and BCG Vaccine Laboratory in Guindy—were restored.

It’s really about workforce training and management. The challenge is how do we continue doing that in PSUs of all kinds. The knowledge upgradation that happens in the private sector doesn’t necessarily work in the government sector.

-senior Department of Biotechnology official

These three, along with BIBCOL and Indian Immunologicals Limited, are the only surviving central vaccine PSUs in India. Apart from them, there are two state vaccine PSUs. This clutch of 7 is a far cry from the 29 public sector vaccine institutes that operated in India in the 1980s, according to Madhavi Yennapu, a scientist at the National Institute of Science Technology and Development Studies who has worked extensively on vaccine policies.

“It’s a common byproduct of liberalisation — the public sector is no longer fashionable,” said Yennapu, who has contributed to the 2021 Routledge publication Immunization and States: The Politics of Making Vaccine. “BIBCOL was set up with the intention of making India self-reliant, with technology from Moscow. After India was declared polio-free, it looks like the government feels there’s no need for indigenous production in spite of good manufacturing facilities.”

Senior officials at the department say that BIBCOL has to surmount several challenges, the main one being workforce training and upskilling. This is compounded by BIBCOL being a fill-and-finish facility, unlike most private companies that also do their own vaccine culturing.

“It’s really about workforce training and management,” said the senior Department of Biotechnology official. “The challenge is how do we continue doing that in PSUs of all kinds. The knowledge upgradation that happens in the private sector doesn’t necessarily work in the government sector.”

The Department of Biotechnology has already submitted a proposal for a renewal package to the Ministry of Science and Technology. Though still at the drawing board stage, the department is hopeful for BIBCOL’s revival, especially with the 2024 Union budget emphasising biomanufacturing and biofoundry.

“We’re looking at it in a positive way,” said the official. “It’s an opportunity to reset.”

Also Read: Visible infra progress, Make in India push — what’s driving PSU stocks to meteoric highs

Very little hope, lots of anger

Meanwhile in Bulandshahr, BIBCOL employees are increasingly frustrated. At noon on a Tuesday, they wrapped up their daily strategy session in the large central hall of the administration building, drafting a list of contacts to press their case. Some workers broke into small groups to plan their next move.

“Disinvestment is a matter for later. First, we have to hold the administration accountable for letting this happen!” said one disgruntled worker to a round of rallying cries.

“We want the government to make a fast decision — that’s all,” said Kiranpal Singh, an employee at the plant for 25 years. “All of us are mentally disturbed and caught in a limbo. If there’s a problem, tell us, so at least the management can take a call.”

Many workers are convinced that the reassurances from the department of biotechnology are just eyewash. And the brotherhood between them is wearing thin — they can’t repay the money they’ve borrowed from each other.

The wasted potential of their beloved plant hangs in the air. Sunil Sharma says he has no tears left to cry.

“We want the government to at least take cognisance of what’s happening with us,” said Kaushik, who has been preparing the other workers for the possibility of disinvestment. “At least tell us if we’ll be open or not. It’s still a functional facility that can produce any vaccine, we just need the right management and the right budget.”

The workers have exhausted all options, from bus trips to Delhi to opening X accounts just to tag officials about their grievances. Now, they plan to march to the capital. What has added insult to injury is that during both the state and Lok Sabha elections, politicians from all sides visited the plant and promised to raise the issue, only for the workers to never hear from them again.

On 25 January, Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Bulandshahr for a rally. His convoy and all accompanying cars filled the plant’s campus. His arrival sent a surge of energy through BIBCOL— perhaps this would be the moment Modi announced the plant’s revival, heralding a new dawn for vaccine manufacturing.

The workers waited patiently to meet him, holding their breath for an announcement that never came. And they’re still waiting.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)