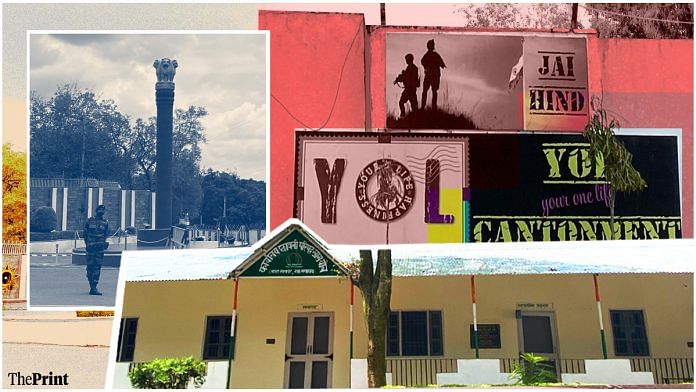

Yol (Himachal Pradesh): Smoke billows out of the office, documents scattered on the floor as files are being torched, and furniture moved out. Officials of the Khas Yol cantonment board in Himachal Pradesh run against time to shut the establishment.

With the Narendra Modi government’s landmark new decision to transfer Army cantonment land to civil municipal authorities, an old way of life established during the British colonial era is ending. Yol is set to be the first off-the-block for this epoch-shifting transition.

The single-story building with an unpainted tin roof has been the centre of the hillocks administration for eight decades—managing the civil areas of a military establishment—running water lines, electricity transmission, mandating land use norms, and dealing with waste disposal for the hill-towns non-military folk.

The cantonment board’s tenure, which began on 31 January 1942, was brought to an abrupt end in the last week of April.

The Army notification now abolishes the cantonment board at Yol. Significantly, the Army has touted the change “as an end to archaic and colonial practices.” Cantonments have existed in India for over two centuries, with the first being set up in Barrackpore in 1765 by the East-India Company.

This dissolution is a precursor to a larger implementation—dissolving the remaining 61 cantonment boards, which control over 1.61 lakh hectares of land in the country. According to government data, this includes 25 cantonments under the central command, 4 under the eastern command, 19 under the southern command, 12 under the western command, and 1 under the northern command.

Traditionally, the dissolution of cantonment boards has divided opinion. Advocates for the move have argued that it is essential to enable easier living for civilians and allow development of the areas at a more substantial pace. Opponents, on the other hand, have stated that it could jeopardize the Army’s administration and way of life.

“The cantonment board abolishment is a significant and important rule change. The Army has been deliberating for years. Management of civil land should be under civil administrations. This is good for development,” Lt. General Deependra Singh Hooda (retd), former GoC-in-C Northern Command tells ThePrint.

As the frenzy to close down the establishment engulfs the officials, a middle-management executive of the erstwhile board tells ThePrint, “The Khas Yol cantonment board has now officially ceased to function.”

“We are fulfilling the last formalities. The handover is taking place with the municipality. Our staff has either been absorbed in the state government or at other cantonments,” the executive adds.

Though, in the small Himalayan town, there exists a duality in reaction to the dissolution of the cantonment board. While residents greeted the news with excitement, and await the fruits of faster development, they also expressed caution and anxiety at the current impasse the move has brought. Former employees of the cantonment board expected the dissolution.

“The process to shut the cantonment board has been going on for over 10 years. This isn’t a new idea. We were expecting this for a while,” a clerk at the cantonment board tells ThePrint, with a sense of remorse over the dissolution.

Also read: Hajj frauds, umrah scams are trapping Indian Muslims. Pay and get ghosted

Excited but cautious

A kilometre north of the cantonment board, parallel to Yol’s main link road, the town market is bustling with activity. The market stretches across the expanse of the Palampur-Dharamshala road that cuts through Yol, with shops on the ground floor and residences on top.

The road also acts as a natural buffer between the civilian side of Yol and the military station.

Assembled at a local confectionery, a group of local people animatedly discuss the abolishment of the board. “We don’t hold any grudges with the cantonment board. But support its dissolution,” says Manish Sethi, a property owner in Yol.

Access to central government welfare schemes, easier laws for construction, the ability to increase the height of our buildings, and more efficient land use norms will now apply to us. This will be beneficial, Sethi adds.

“It is significant that the dissolution of cantonment boards in India began from Yol,” says Anjali Walia, a cashier at a garment shop.

Yol, Sethi explains, was the easiest to start the process of dissolving the board as there was an easy and clear segregation between civil and military land.

Despite the excitement, residents remain anxious due to the uncertainty and disruption to civic administration brought about by the sudden dissolution of the cantonment board.

Khas Yol cantonment board documents accessed by ThePrint show the large administrative ambit under their charge—including managing over 15 kilometres of village roads, 1,500 drains, 670 water connections, 249 streetlights, and 05 schools.

Garbage collection stands out as one of the most visible disruptions and negatives of the board’s dissolution. “Waste disposal has become a major issue now. There is garbage lying all over and no one is there to collect it,” says Paramjeet Singh, a restaurant owner.

Singh complains of excessive difficulty in disposing of waste from his restaurant. “I can’t just throw the wet waste onto the road. We have to go far away and dump into random open areas. It’s also so unhygienic and bad for health,” he adds.

Another drawback of the cantonment board dissolution has been related to the water supply. “The water supply stopped for the first few days after the board was dissolved. The local MLA had to be contacted and he resolved the issue,” says Sandhir Malli, a business owner in Yol.

“We also now don’t know where to go to get a life-or-death certificate. Currently, there is ambiguity about who will take over the role of the board,” adds Sethi.

Alluding to the lack of administrative clarity, Anjanli Walia says, “We don’t know whether Yol will be absorbed into the neighbouring panchayats, or a new panchayat will be set up for administration. This needs to be resolved quickly for efficient governance.”

ThePrint contacted the Deputy Commissioner of Kangra via phone and text to seek clarity on the future of Yol’s administration. However, there was no response till the time of publication.

Also read: Madhya Pradesh is richer than Bihar. So, why is it still lagging behind in health?

Steep house tax but no parks

Back at the cantonment board, as the remnants of the quasi-military institution are taken apart, an administrative assistant says, “The steep increase in house tax rates began the downfall of the housing board. People did not like this move.”

According to local people of Yol, the cantonment board arbitrarily started to increase house tax rates over the last decade. This, they explain, even amounted to 4-times or 5-times the earlier rates.

As the debate continues at the confectionary shop, Sethi says, “The continuous rise in house tax over the last few years turned sentiment against the board. It was unfair and contrary to any principles of land tax rates.”

Sandhir Malli says that the residents even approached the board several times to discuss the house tax rates and advocated for its rationalisation, however, their efforts fell on “deaf ears.” At least now we won’t have to pay “crippling house tax,” Malli adds.

Apart from the tax rates, locals even state that there was no infrastructure built by the board for children. “On our side, there are no recreational facilities for children. Not even a park was built by the board. Contrast this with the many facilities in the military station” says Kamaljeet Singh, an owner of a convenience store.

Despite these negatives, the consensus from the residents is that the board did a relatively decent administrative job, though the civic upside is now more apparent.

Summing up the sentiment in the town, a local administration source says on condition of anonymity, “There are always two sides to any story, some residents are happy with this change as work could move faster, while some are sceptical due to the change affecting them directly.”

Also read: A band of scientists, students, engineers is stealing the IMD thunder—one forecast at a time

The cantonment beyond the hillock

Beyond the hillock in Himachal, cantonments have existed in India for over two centuries. As a consequence, a way of life, a unique and intricate civil-military confluence has developed. This, experts point out, could create complications for the abolishment process ahead.

“Cantonment board dissolution and segregation of civil and military areas will be far more complicated in other parts of the country,” Mandeep Singh Bajwa, a military historian tells ThePrint.

In many cantonments, Bajwa explains, there is a deep intermingling of civil and military spaces. You suddenly find a civil pocket in a military space and vice-versa. This will have to be considered in the disintegration process going ahead.

Unpacking the roadmap for the dissolution of the remaining 61 cantonments, Lt. Gen Hooda (retd) says, “Yol was easy as there was a clear segregation between the military and civil land.”

However, Hooda adds, for the remaining cantonments the process will have to be “selective”. The dissolution must be carefully and intricately carried out in the remaining areas. Essentially, it will depend on the extent of intermingling in the respective cantonment.

Bajwa also points to the impact cantonment dissolution could have on the quality of Army life.

“Another problem is that in many cantonments—the sports areas, the golf courses, the clubs, the recreation infrastructure, and accommodation are in the civil parts. These may be lost out now due to the rule changes. This could adversely affect the Army’s way of life,” he adds.

Further, with the civil part of cantonments now deemed to be under regular municipal laws, experts believe that the land can be taken over by monopolies.

“Given that cantonment land in many cities is in prime locations and city centres, there will be land sharks who will try to take over large swathes for development. Municipal administrations across the country will have to be wary of this and prevent any illegal practices and developments,” a defence analyst explains.

At the Yol market, the discussion at the confectionery has ended in an impasse with the residents hoping for a quick resolution to the current administration quagmire. A few metres ahead from the confectionery, the market bends into a narrow lane, which opens into a row of houses.

Sitting outside one of the houses, Suresh Kumar, a cab driver says, “At least now all state and central government schemes will apply to us. We won’t always be behind the curve on development.”