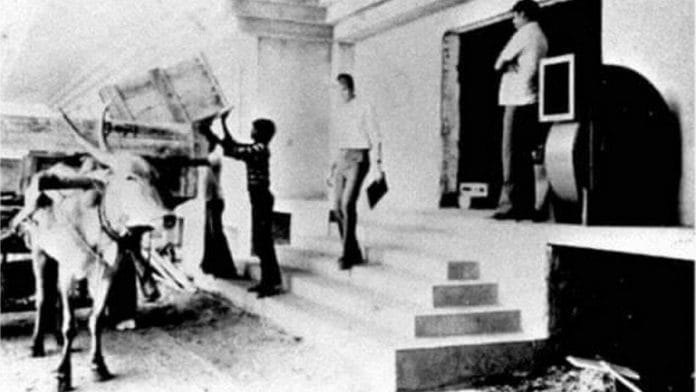

New Delhi: The white bull pulled a cart along the busy Miller’s Road and stopped outside Sona Towers in Bangalore. A now classic black-and-white photo shows workers unloading its high-tech cargo: India’s first private satellite dish. It had been brought in to enable communications with the US for Texas Instruments (TI), an American company that had just set up an R&D facility to design electronic chips, or semiconductors.

Since that day in 1985, Bengaluru has become an international tech and entrepreneurial hub. The semiconductor industry, too, has exploded. Chips are now ubiquitous in just about everything electronic — from rice cookers and mobile phones to cars and missile systems.

Yet, for a variety of reasons and despite a promising start, India lost out in the semiconductor revolution of the 1980s, while countries like China and Taiwan raced ahead.

The state-owned semiconductor fabrication foundry in Mohali, Semiconductor Complex Ltd (SCL), literally went up in flames in 1989, and with various government initiatives fizzling out, India over the 1990s and 2000s settled into the role of a semiconductor design backroom rather than the manufacturing powerhouse it once hoped to be.

Over the past 15 years or so, however, a handful of homegrown semiconductor design companies in Bengaluru have been pushing to be recognised for their innovation, rather than as proverbial ‘bullock carts’ on which foreign companies ride.

For instance, Terminus Circuits owns the intellectual property for the chips it designs for its clients — which is a rarity. Then there’s Saankhya Labs, which designed the first consumer electronics chip for Software Defined Radio (SDR) communication systems in 2012. Steradian Semiconductors works at the cutting edge of 4D imaging radar technologies.

Now, more than ever, the importance of such companies is being recognised.

India, which currently imports 100 per cent of its chips, was hit hard by the worldwide chip shortage, exacerbated by Covid and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Like the rest of the world, the country is keen to achieve some chip self-sufficiency.

Last December, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) launched the ‘India Semiconductor Mission’ to enable the country’s “emergence as a global hub for electronics manufacturing and design”, with a total budget of Rs 76,000 crore (about US$10 billion).

In April, the government also set up a panel to support start-ups and SMEs (small and medium enterprises) in the sector.

Several start-ups are hopeful that the government’s semiconductor push will allow them to overcome hurdles and boost their international stature.

As Ashish Lachhwani, cofounder of Steradian Semiconductors puts it: “The world doesn’t cut you slack because you are a start-up from India.”

Also Read: You thought you’ll buy an EV to beat the chip shortage delaying car deliveries? Tough luck

Why semiconductors are critical

Semiconductors — also known as microchips, integrated circuits, and processors — are embedded in all electrical and electronic devices. Most devices comprise an ecosystem of chips controlling different functions.

Chips are integral to just about everything electronic: smartphones, cars, trains, washing machines, traffic lights, computers at the stock exchange, fighter jets. But they didn’t invite much public attention until there was a shortage stemming from supply disruptions due to Covid lockdowns. Because of this, many goods were either unavailable or had become more expensive.

Governments realise chips are important to national and economic security. A March 2021 note from US chip leader IBM said: “You never want to be in a spot where another nation can control a valuable resource that your nation depends on.”

This is why the US government is now looking at resolving the semiconductor supply issue by investing “at least” $50 billion in the sector.

India wants to play catch-up too, for reasons that are also geopolitical. Manufacturing is currently concentrated in countries like Taiwan, which remains under the threat of a possible invasion from China. Another semiconductor hub, South Korea, is constantly under the threat of war from its neighbour North Korea.

This April, for the first time in India’s history, a Prime Minister inaugurated a conference just about semiconductors, ‘SemiconIndia 2022’, sending a clear message that the tiny chips had become important enough for the country’s premier to put his face to.

On 4 July, PM Modi also launched Digital India Week 2022, which includes a programme on semiconductor designing.

In May, the International Semiconductor Consortium (ISMC) made up of Abu Dhabi investment firm Next Orbit Ventures and Israel’s Tower Semiconductor announced a $3 billion chip fabricating plant in Karnataka.

Next Orbit Ventures’ founder-managing partner Ajay Jalan told ThePrint that the fund is a “firm believer” that its investment will help achieve PM Modi’s vision of a $5 trillion economy.

Last month, the chairman of the Taiwan-based electronics giant Foxconn met with Vedanta Group’s chairman to chalk out a plan for a chip manufacturing plant, for which they had signed an MoU in February.

But semiconductor manufacturing is notoriously difficult and expensive. Catching up is not going to be an easy or quick task for India, given that making state-of-art chips requires billions of dollars of investment, pure raw materials, and solid infrastructure. A patchy water supply or power outages could be disastrous for a semiconductor plant.

As some observers have pointed out, the most realistic hope right now is that the Modi government follows through on local chip industry plans.

Also Read: Vedanta’s latest chip venture with Foxconn is just a little more than a piece of paper

Local talent, but no industry growth

India’s semiconductor story is a regrettable litany of missed opportunities and failures.

As journalist Choodie Shivaram summed up in a February 2022 article for The Statesman: “In 1987, India was just two years behind the latest chip manufacturing technology. Today, we are 12 generations behind.”

The only government-owned fabrication plant, Semiconductor Complex Limited (SCL), started operations in 1983 in Mohali, but a fire six years later knocked it out of commission until 1997. While there were half-hearted attempts at joint ventures to get it back on track, nothing worked out.

The SCL still exists, except that it has been downsized into the Semi-Conductor Laboratory (SCL), which focuses on R&D. In March this year, the government announced plans to “upgrade” the facility, but the jury is out on how much it can achieve.

Today, manufacturing is heavily dominated by giants like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and South Korea’s Samsung Electronics.

However, where India does have an edge is its engineering talent. Almost all the top international chip design companies have a presence in India, which is reportedly home to 20 per cent of the world’s semiconductor design engineers.

So far, much of this talent has been leveraged by foreign companies, starting with Texas Instruments (TI), which in 1985 was the first international tech company to set up shop in Bengaluru.

“India has brilliant engineers. TI saw a great opportunity very early on to leverage this technical talent to build world-class products,” Santhosh Kumar, president and managing director of TI India, told ThePrint.

Then there is semiconductor pioneer Intel. Its largest design and engineering centre outside the US is in India, with facilities in Bengaluru and Hyderabad.

“India today has the distinction of designing over 2,000 chips every year,” Ajay Sharma, Intel India’s senior director for strategy and business development, said.

Nevertheless, while the competence of Indian engineers is widely praised, they have not generally been known for innovation or significant value-addition.

Ashish Lachhwani, cofounder of Steradian Semiconductors, said only a few multinationals like TI set up India teams to work on core functions like definition and architecture of the chip.

An executive at an Indian semiconductor firm said on condition of anonymity, “To this day, India mostly does the verification job of checking if the chip works as expected. It’s a job that is easy to offload to other countries.”

However, there are some companies that have been working to change the status quo for years.

A push for recognition

In 2006, Hemant Mallapur, Parag Naik, and Vishwakumara Kayargadde decided to take a gamble. They quit their jobs with the California-headquartered semiconductor firm Genesis Microchip and started their own venture, Saankhya Labs.

“We were doing all the product development in India but since the company headquarters was in America, naturally the product was considered a US product and not an Indian one,” Mallapur told ThePrint.

“Over our brainstorming sessions during post-lunch walks we decided to quit and start our own semiconductor company,” he added.

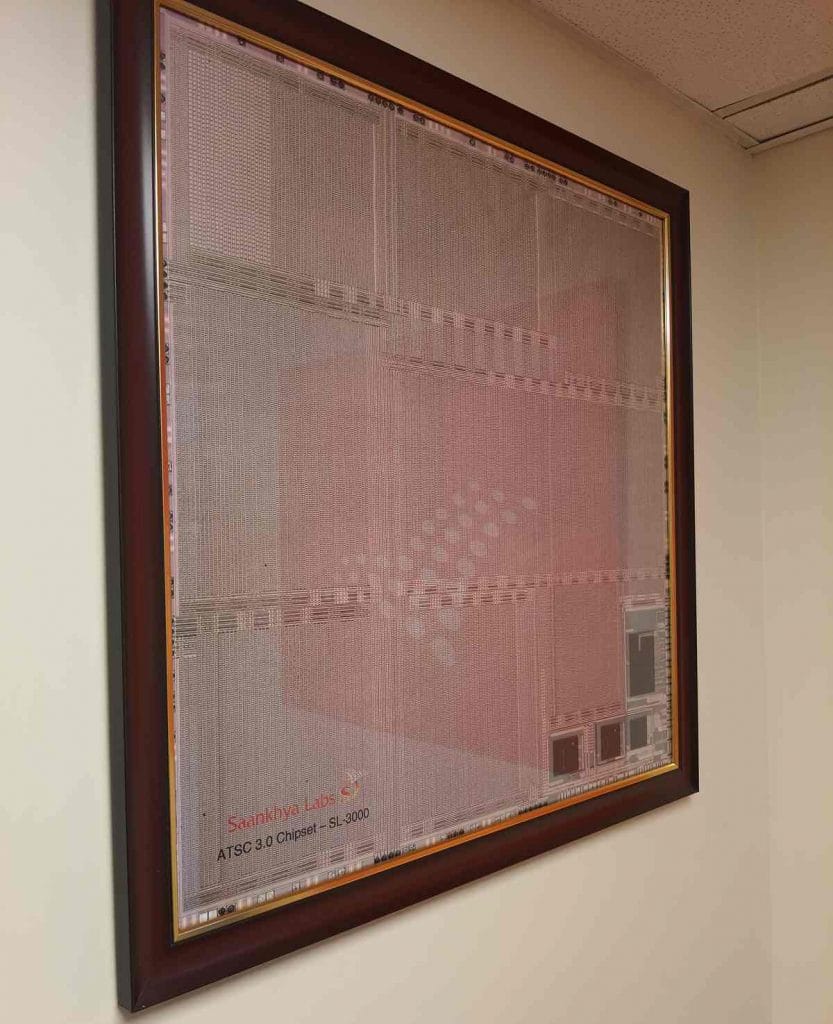

At Saankhya Labs’ Bengaluru office, a framed picture takes up pride of place in the conference chamber. At first glance, it looks like a close-up of TV static. But that’s not what it is.

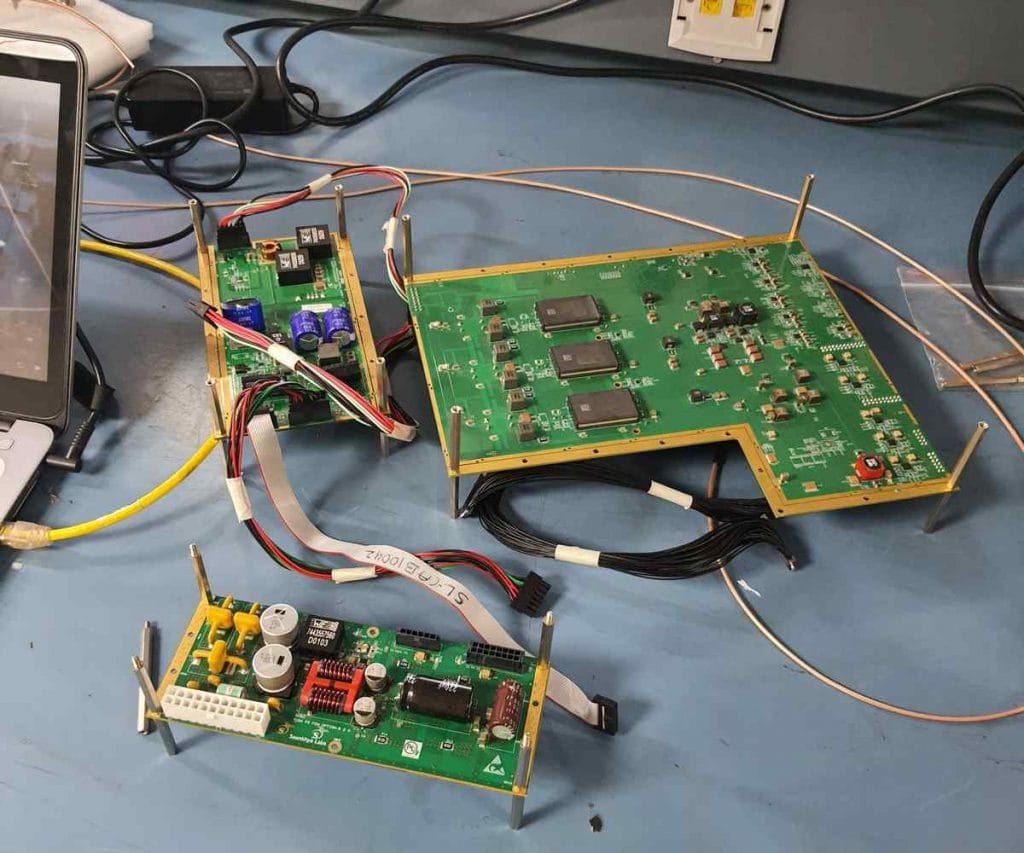

It’s actually a blown-up picture of an advanced chip, which the company developed in 2019 in collaboration with a subsidiary of the American telecom conglomerate Sinclair Broadcast Group and Samsung’s semiconductor foundry.

It took 100 engineers two years to design the circuit diagram, including the placement of components called transistors — that a foundry later prints on a wafer of silicon — designating how electricity will flow through it. The look of black lines on a glitchy TV comes from the ultrafine micro-wires connecting the billions of transistors on the silicon chip.

In press releases, the ATSC 3.0 chip is described as the key to a “disruptive future in a 5G world”, with Saankhya Labs getting billing along with Samsung and the Sinclair Group.

But Saankhya has made its own name too.

In 2012, the start-up designed the first consumer electronics chip for Software Defined Radio (SDR) communication systems.

An SDR chip is a software-controlled chip that can mimic the effects of multiple hardware components needed for a full-fledged radio communications system, but without all the heavy investment. If you Google ‘SDR chipset’, Saankhya’s name is on top of the search results.

Then there is Terminus Circuits, another Bengaluru-based semiconductor circuit design firm. Its founder Dr Sankar Reddy said he started it because, “I thought, why can’t we?”

“There is no dearth of knowledge, resources, educational institutes,” he added. “Why can’t we create intellectual property of high complexity? So, I built and trained a team from scratch to make technology for the future.”

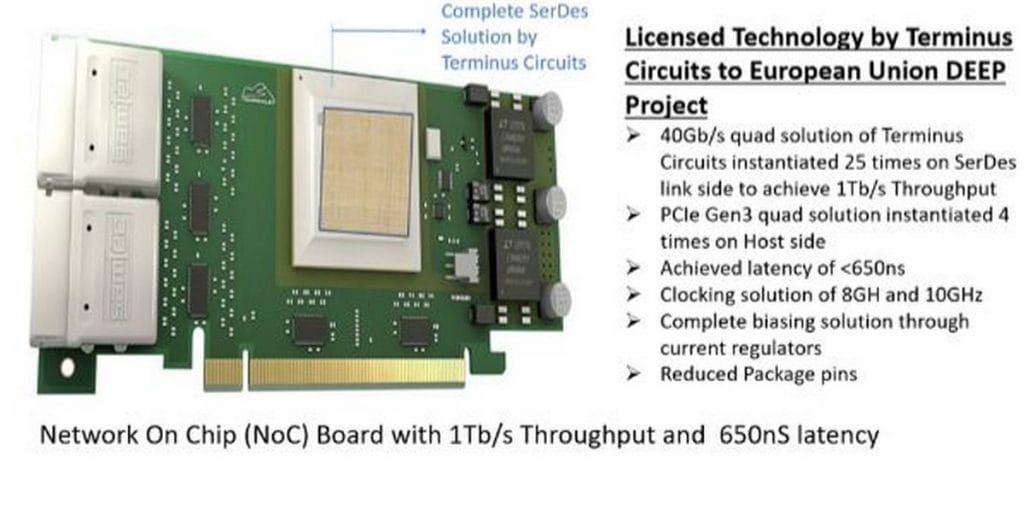

Terminus is an outlier in that it owns the intellectual property for the chips it designs for its clients. For example, it designed the hardware component for a “network on a chip” for a German company for use in the EU’s goal to set up high-performance computing infrastructure.

Terminus owns the intellectual property for the components it designed, not the German company.

Despite achievements like these, most Indian chip start-ups have struggled to get a firm footing.

A struggle for investments, bureaucratic hold-ups

The business of semiconductors is capital-intensive, and finding local investors is a struggle, Mallapur said.

Back when Saankhya started in 2006, it took the company six months to raise the first bit of money and three years to make their first chip. In 2013, designing a new chip required about $25 million, but Saankhya couldn’t drum up the funding. The company had to pivot to building a product for rural internet connectivity and lay off employees.

Then, in 2016, a potential investor backed out because of the Euro economic crisis. The day was saved only when work came from a Hyderabad-based company to build a radio communication system for a defence client. “That brought in significant revenues and pulled us from the brink,” Mallapur said.

The late Dr Mahant Shetti, a semiconductor veteran who played a key role in TI, was one of the few major Indian contributors to the local sector, Mallapur added.

He invested in start-ups like Saankhya, set up a company called KarMic Design in Manipal to do semiconductor work outsourced by global firms, and established chip design training centres in rural Karnataka with his own money. Shetti died in 2017.

Steradian Semiconductors, which specialises in making the chips and associated devices for automated traffic management using radar technology, also had a slow start in 2016.

A major problem, according to founder Ashish Lachhwani, was being taken seriously by global firms.

However, in 2018, the company partnered with Japanese firm Renesas Electronics, a world leader in microcontrollers, and Visteon, a billion-dollar American electronics supplier for the automotive sector. “It took several years to develop trust, but they picked us when they could have chosen anyone in the world,” Lachhwani said.

In addition to funding issues, companies in India struggle with Indian laws that are built to stop wrongdoing but end up obstructing operations.

For example, Indian laws don’t allow importing second-hand equipment to stop e-waste piling up here. So, when a young company needs equipment for a short time to test something a client wants, it gets stuck, Lacchwani said.

This equipment, he added, is otherwise only available at specialised government labs of DRDO and Bharat Electronics, and India lacks the culture of open access that exists in the US or Europe.

‘Need long-term policy’, not one-off ‘reimbursement schemes’

While Indian chip companies are glad about the government’s semiconductor push, they believe that a long-term, strategic approach is of critical importance.

Dr Sankar Reddy of Terminus Circuits welcomes the government scheme to encourage companies to set up semiconductor foundries or fabrication plants here in India, but says “immediate results” should not be expected.

“I strongly believe that setting up fabs should be a strategic move as it is high in investment (about $5-10 billion) and it takes at least five to six years to break even.”

What is not needed, Lachhwani said, is a “repeat” of the government-owned semiconductor lab and fabrication plant in Mohali. A phased approach would work best, according to him — starting with a fab that uses mature technology processes, and then graduating to using cutting-edge tech to build more complex chips.

“India needs a 20-year semiconductor policy and not occasional reimbursement schemes,” he added.

Mallapur outlined the need to keep the electronics industry abreast of policy changes well in advance of their implementation.

In 2011, for example, the government made digital set top boxes mandatory for TV viewing. If a few years of advance time had been given before the announcement, Mallapur said, set-top boxes “could have been made using semiconductors and systems from Indian companies instead of being imported from China”.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Offering access to high-end gizmos, these spaces in Bengaluru are helping startups make in India