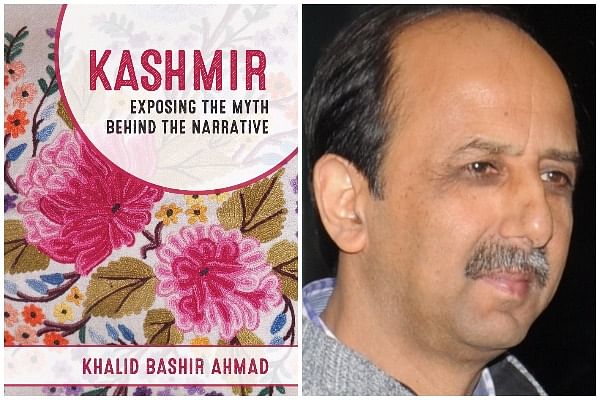

Kashmir: Exposing the Myth Behind the Narrative (SAGE Publications, 2017), a new book by a former Kashmiri state civil servant, Khalid Bashir Ahmad, challenges what the author calls Kashmir’s popular ‘Hindu historiography.’ According to Ahmad, the historical text Rajatarangini (by Kalhana) is inaccurate, as well as the popular narrative that Islamic settlers’ forced mass conversion on Kashmiri Hindus, expelled local populations, and wantonly demolished non-Islamic religious symbols. The book also says that the region’s residents practiced Buddhism for over a millennium before ‘militant Hinduism’ obliterated the religion.

Ahmad claims that a Kashmiri Brahmin minority and its progeny successfully perpetuated this fallacious narrative over centuries. Following the advent of armed insurgency and the subsequent mass migration of Kashmiri Pandits in 1990, the book claims, this communal narrative became the mainstream Indian view.

Does the Rajatarangini narrative of 5,000 years of Hindu history in Kashmir need challenging? We ask experts.

The gifted versifier Kalhana himself alludes to using his ‘mind’s eye’ in composing his work

Khalid Bashir Ahmad

Author, ‘Kashmir: Exposing the Myth Behind the Narrative’

Kashmir is known to have an ‘uninterrupted’ recorded history of five millennia with the Rajatarangini, composed by Kalhana, a 12th century native Sanskrit versifier, recording the first 4,000 years. His narrative is strikingly precise to a couple of centuries prior to his own time, but incredibly fictional for the first 3,000 years. The narration of this period is a description of persons and events untraceable in other sources. The gifted versifier himself alludes to using his ‘mind’s eye’ in composing his work while trashing all the other 11 sources of history (that he had himself consulted) for ‘author’s misplaced learning’ or ‘no longer existing in complete state’ or having become ‘fragmentary in consequence’ or ‘lack of dexterity in the exposition of the subject-matter’ or ‘no part being free of mistakes’.

Did he construct prehistoric Kashmir with the same poor sources or purely with his poetic imagination?

The ruler Rinchana was himself among the first converts. The allegation of widespread destruction of temples disregard factors like the massive earthquakes Kashmir suffered in history, as mentioned in geological studies. Two hundred years after the alleged iconoclast Sikandar, we have Mirza Haider Doghlat (16th century) and Jahangir (17th) who describe more than 150 ‘lofty’ idol temples standing as ‘first and foremost among the wonders of Kashmir’ built ‘before the manifestation of Islam’.

The Kashmiri Hindus, as ‘eyes and ears’ of the successive rulers, have held important positions throughout the Muslim (Shahmirs, Chaks, Mughals and Afghans) rule and remained the preferred community for the positions of power and trust. Even Aurangzeb accorded them ‘very high place in the country and the local bureaucracy’. The Mughals even banned Muslims from recruitment in the army while keeping its doors open for the Pandits.

The truth is on our side in the form of the Sun temple in Martand, ochre mark behind the Shah Hamdan mosque

Rahul Pandita

Author, ‘Our Moon Has Blood Clots: The Exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits’

In 2015, Germany returned to India a 10-century Durga idol stolen from Kashmir Valley in the early ’90s. It became only possible because of a long struggle by a Kashmiri Pandit friend settled in the United States. After its return, we spoke for long. I told my friend that someday someone in Kashmir will write that there were no Pandits in the Valley. The cultural effacement is being perpetrated through the likes of Khalid.

It is a big, well thought-out project. On one end is the denial of the circumstances that led to the recent exodus of the Pandits in 1990. Gradually, they are gnawing, rat-like, at the troubled history of our land, creating false, fictional narratives masquerading as serious, academic work. This includes whitewashing atrocities of Islamist invaders and terrorists of 700 years and portraying the Pandit as the oppressor.

The Pandits do not have rap artists and ‘resistance’ singers; we do not have the support of tenured professors in Berkley. But the truth is on our side. It is there in the form of the Sun temple in Martand; it is there in the form of the ochre mark behind the Shah Hamdan mosque. Serious Kashmir scholars know Kashmir’s history and its tryst with Islamic invasions. Khalid’s book is not meant for them; it is meant for local consumption in Kashmir so that those who drove out the Pandits from their land and brutalised them can feel guilt free.

Kalhana’s Rajatarangini is an unbiased, clear historical writing without any pressure from the kings

Rajneesh Shukla

Sanskrit Scholar, Sampoornanad Sanskrit Vishwavidyalaya, Varanasi

Rajatarangini (‘Flow of Kings’) is a historical chronicle of early India, written in Sanskrit verse by the Kashmiri Brahmin Kalhana in 1148, and is justifiably considered to be the best and most authentic work of its kind. It covers the entire span of history in the Kashmir region from the earliest times to the date of its composition. Kalhana is regarded as Kashmir’s first historian. Like the Shahnameh is to Persia, the Rajataringini is to Kashmir.

Kalhana is a renowned name in the world of history, not just because of his work on Kashmir, but also because of what he wrote about the process of historiography and introduces the qualities of a good historian. He argues why his Rajatarangini is better than the previous texts. Among his sources were a variety of epigraphic sources relating to royal eulogies, construction of temples, and land grants, coins, monumental remains, family records, local traditions.

Kalhana was able to write an unbiased and clear historical writing without any pressure from the kings because he didn’t get patronage from any king of his time. His writing was devoid of rhetoric and praise, which was visible in the works of other writers under the patronage of the kings. Kalhan says, “A good history has the power to take the person into past and explore in a way like an eye witness. That history involves a superior kind of creativity which retains its relevance even after many centuries. That historian should be appreciated who honestly judges the past incidents; unaffected by his personal likes & dislikes.”

Kalhana delved deep into such works as the Harsacarita and the Brihat-Samhita epics, and used with commendable familiarity the local rajakathas (royal chronicles) and previous works on Kashmir as Nripavali by Kshemendra, Parthivavali by Helaraja, and Nilamatapurana.

Buddhism and Hinduism were never at loggerheads in Kashmir

K. N. Pandita

Former Director of the Centre for Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir

History of all ancient civilisations carries an important component of mythology. This is how humans have attributed supernatural powers to saints, prophets or angelic bodies. So, Christ can breathe life in a dead body, Muhammad can split the moon into two with the show of a finger and Hanuman can lift Sumeer Mountain on the tip of his small finger.

Buddhism and Hinduism were never at loggerheads in Kashmir. Their co-existence was proverbial. If the Hindu king ordered construction of temple consecrated to Vishnu, his queen ordered construction of a vihara consecrated to Buddha or Boddhisattava. Hindus never changed the nameplaces of Buddhists in Kashmir. The place-name suffix “yaar” or “haar” are actually the corrupted abbreviations of Sanskrit vihar.

Somyaar, Kharyaar, Naidyaar localities in Srinagar city or Kralhaar, Frestehaar localities are in close proximity of Kanispora (ancient Kanishkapora five kilometres south of Baramulla where probably fourth Buddhist conference attended by Hiuen Tsang was held) and are still called by the same nomenclature even by the Muslims of Kashmir.

Second, it is ignorance of ancient history of Kashmir to use the term “militant Hinduism”. This is the coinage of 20th century Indian Muslim League of the sub-continent to suit their political perception. Great humanism of Hindus of ancient Kashmir is proved by their Shaivite scholars taming the brute murderer Mihirkul of Hun descent and making him give up his killer nature and embrace Shaivism.

Exclusivist vision of Kashmir’s history is being used to suit a certain hegemonic account of the past

Noor Ahmad Baba

Professor in Political Science, Kashmir University

History cannot be understood from one lens alone. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, which chronicles rulers of Kashmir from about 19th century BCE to about 12th century, is not a professionally written historical account. It is an epic account of kings written in literary form covering a limited period and gives at best a partial and incomplete account of Kashmir history. Such a narrow account cannot be sufficient to construct a more comprehensive account of Kashmir’s past. We need to reconstruct the history in the light of archaeological and ethnographic evidences.

There is never one history of the past. History has always been written from the perspective of the dominant and victorious communities and races. Kashmir, as per more contemporary evidence, has had human habitations even before the arrival of Aryans and initiation of the Hindu period covered in Kalhana’s account. Such a history written from the one perspective cannot be an objective and complete account of history of any place and people. To equate a place with one people is a myth constructed to project a certain partisan narrative of history. Such an exclusivist vision of history has been and is being used to suit a certain hegemonic account of the past to force assimilation on the marginalised communities and people. Such notions need to be deconstructed and replaced by a more objective account of the past, drawing from more objective sources available today.

The narrative on forced conversion doesn’t hold much weight as the privileged (Brahmins) within Hindus continued to be intact in Kashmir in spite of mass conversions of people from lower caste people to Buddhism at one time and to Islam at a later stage.

The most graphic description of annihilation of the Hindu temples of Kashmir is given by a Persian biographer

Ashutosh Bhatnagar

Director, Jammu Kashmir Study Center, New Delhi

Any writing claimed as history may be challenged, if it has no supporting sources, references, evidences.

“But-shikan”, the iconoclast, is the sobriquet given to Sikandar (Alexander) by Muslim and not Hindu historians. Almost all Persian histories of Kashmir eulogise his campaign of destroying Hindu temples and shrines as great and laudable service to the expansion of Islam. This and his forcible conversion of Hindus to Islamic faith has been vividly told by the Muslim author of Baharistan-i- Shahi (A Chronicle of Medieval Kashmir translated by K.N. Pandita and published by Gulshan Publishers, Srinagar, 2017).

The most graphic and vivid description of annihilation of the Hindus of Kashmir, their temples and shrines and their civilisational symbols as well as their forced conversion is given by the author of Persian biography of Shamsu’d-Din Araki, an Iranian of Noorbakhshiyya sufi order who visited Kashmir twice – last time in about AD 1574. This work is titled Tohfatu’l-Ahbab and has been translated with exhaustive and valuable footnotes by K.N. Pandita under the title A Muslim Missionary in Medieval Kashmir.

An author, claimed to be an historian, must be humble enough to accept the realities of history. It seems that the idea behind the Khalid Bashir Ahmad’s book writing is not to reveal the truth but to produce a propaganda. It is very unfortunate that the author used his skills to deny the history of the land, to which he belongs.

The book tries to settle the 1990 debate by proving that Kashmiri Pandits lied since 8th century

Vinayak Razdan

Runs an online archive of cultural and visual history of Kashmir

The book is the latest fat brick from Kashmir that is going to be thrown at Kashmiri Pandits. It should have been titled “Kashmir Pandits: the race of liars”. Written by a former director of Libraries, Archives Archaeology & Museums of Kashmir, it basically tries to settle the 1990 debate by proving that Kashmiri Pandits have been lying since 8th century, around the time Nilmata was written. He writes that Kalhana hated Musalmaans, and does not use the word “musalmaan”, even though the word existed as proven by famous Lal Ded saying “na booz Hyund ti Musalmaan“. But the saying is of obvious later origin just doesn’t occur to the writer.

He goes on to say that Jonaraja, historian and Sanskrit poet, spread lies about Sikandar just because Jonaraja couldn’t reconcile to the fact that the Hindu era of Kashmir was over. Is the writer reading the past through the lens of present, and is unable to reconcile to the fact that Kashmir is partly ruled by Hindu BJP?

Why was this book written the way it was, rejecting Nilmata, Rajatarangini, 1947, 1967, 1988, 1990?

It was done so because Kashmiri Pandit now tell their story in that sequence. Pandits want to explain 1990 by explaining Sikander. Muslims wanting to negate 1990 by negating Sikander’s role.

But this is probably the first book that actually has the exact FIRs of Kashmiri Pandits who died and were raped. It is another matter that that are used to forward the usual: 1. Not enough died. 2. Pandits exaggerated the descriptions.