Chatto held an important position at the International Secretariat of the LAI as the international political secretary. His job was to reorganise the LAI network with an emphasis on his individual contacts and to turn the LAI into a centre for anti-imperialist activists in Berlin and the rest of Europe. Organising the LAI and meeting anti-imperialists from all over the world would help Chatto feel less lonely in his forced exile, though only briefly. Chatto was the perfect man for this job because he had contacts with both the communists, through Munzenberg, and in India, through Nehru. His language skills were also useful. By now, he spoke French, German and Swedish, in addition to the other languages he already spoke.

Nehru was not very impressed by most of the Indian political exiles, a lot of whom had been mostly forgotten by those back home, though he admired their sacrifices. He would meet several of them, but the only ones who impressed him were Chatto and Roy.

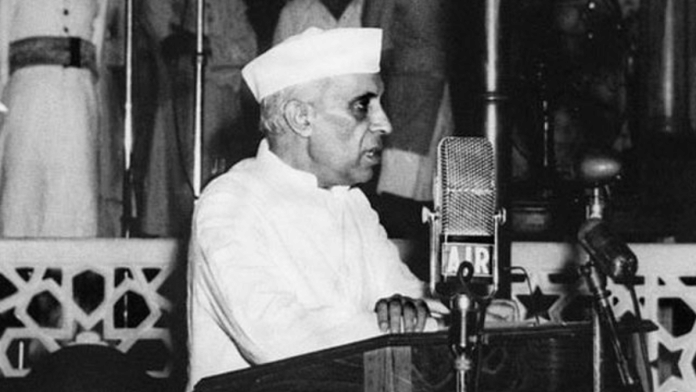

In 1927, Nehru and his sister Krishna Hutheesing met Chatto for the first time in Brussels for the opening Congress on anti-imperialism. Nehru described Chatto as ‘a very able and a very delightful person. He was always hard up, his clothes were very much the worse for wear, and often he found it difficult to raise the wherewithal for a meal. But his humour and light-heartedness never left him.’ Nehru remarked on Chatto’s homesickness and the pull of home that he still carried despite his ties with home being severed. ‘No exile can escape the malady of his tribe, that consumption of the soul, as Mazzini called it.’

Nehru was a staunch supporter of the league in its early years. He wrote numerous friendly letters to Chatto in 1928, discussing matters to do with the league. In a particularly poignant one, he counselled Chatto to not return home because he would likely be arrested. ‘You write to say that you feel very tired and homesick. I can understand the feeling but I do not suppose you would feel happy if you were nearer home. Things are pretty dull here and it is extremely difficult to wake people up. And the feeling of being tired is common enough here too, the only difference being that it is not the result of work but of doing nothing.’

In 1928, Nehru wrote a long and frank pro-labour foreword for a book in which he said, ‘I have had the privilege of being associated with the League since its formation at the Congress held in Brussels in February 1927. I welcomed its formation because I felt that it supplied a common platform for the two great movements of revolt against the existing conditions which we have in the world today, the struggle of labour against the entrenched citadel of capital and the nationalist movements in countries under alien domination.’

Nehru went on to argue that the independence of colonial countries was essential to their inhabitants obviously, but was equally necessary for the much-abused European working class because their lot would not be improved as long as the labour of colonial countries continued to be exploited. The LAI, he said, was the first group of nations which recognised the common cause of Western labour and colonised people. That alone, argued Nehru, was worth its formation. ‘During the year of its existence it has already brought nearer together the various peoples of Asia and Africa struggling for freedom, and it has made them realise in some measure that there is a bond between them and the worker of the West. And gradually even national movements like the Indian National Congress, conservative in their social outlook, are beginning to look towards the socialist ideal of society,’ wrote an optimistic Nehru. He went on to savagely criticise the British Labour party, which was in power at that time, for acting as ‘full blooded imperialists indistinguishable from the more blatant variety belonging to the Tory Party’.

Years later, Krishna and Nehru visited Berlin where they met the lonely Chatto again. By then, Chatto had been away from home for a quarter of a century, living a life of precarious poverty, constantly staying one step ahead of the law. He yearned for family, but he had only a string of disastrous affairs to look back on. Krishna writes that even the stoic Chatto—a man who had risked death for anarchy—had tears in his eyes as they parted. ‘I remember the last smile on his lips which quivered though he tried not to show it. And so, we parted, leaving him a lonely, desolate figure on the platform—we to our home, comfort and security, and he back to his life of hardship, uncertainty and loneliness.’

Nehru and Krishna would continue to hear from Chatto for a few more years, but then eventually the news would stop coming.

This excerpt from ‘Spies, Lies and Allies: The Extraordinary Lives of Chatto and Roy’ by Kavitha Rao has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from ‘Spies, Lies and Allies: The Extraordinary Lives of Chatto and Roy’ by Kavitha Rao has been published with permission from Westland Books.