Every capital city is a benighted one, New Delhi probably more than most. You do not track shifting winds by looking for straws floating there. For that, you go to the countryside, where real voters live, and read the writings on the wall.

In New Delhi you simply sniff the air carefully, patiently, and if you have an experienced nose and a reasonably open mind, you can smell change. Not all change is necessarily for the better, even if it vindicates you, gives you the justification to repeat that most irritating boast, I told you so.

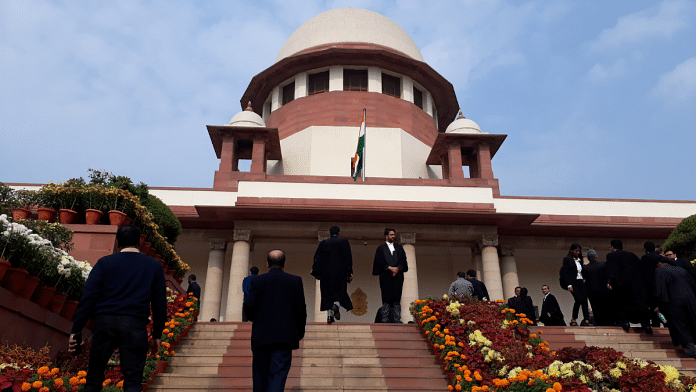

Several times, in the 2010-12 phase as UPA 2 lost control of governance and ceded acres of governance space to others, I had noted how three institutions, the judiciary, media and civil society, were growing too big for their Kolhapuris. All three were grabbing the governance space vacated by the executive.

It was to be expected, as the “system” abhors a vacuum. But it was also as unnatural as it was unsustainable, because soon enough the executive was bound to find its feet. And when that happened, I had said, all three would get it in the neck.

Three diverse, unconnected events over this week deserve attention.

First, the serving Chief Justice of India (CJI) surprised everybody with his suo motu praise for the Prime Minister. It brought him criticism, initially muted, later a bit less so.

Second, and quite unprecedentedly, Priya Pillai, a senior Greenpeace activist, was stopped by immigration from travelling to London while there was no legal bar on her going overseas. There were some protests, but confined to the activist/liberal community.

And third, there was an observation by a Supreme Court bench hearing an appeal by filmmaker Pankaj Butalia against censors not allowing his documentary on Kashmir to be screened. “Why is it one-sided?” asked the bench, giving him no relief, at least not yet. “We don’t know why it has become fashionable and a question of human rights to talk about one side of a story.”

This begs the question: would the honourable court have raised a similar point if it were an even more one-sided Bharat Sarkar documentary?

Also read: If judiciary can’t get its act together, then god save India

Questioning each one of these, however, is not central to this week’s point. In fact the three, together, confirm an original thesis. That, as predicted, the judiciary, civil society and media are all getting it in the neck. They will all be forced to clear out their encroachment of the space that belongs to the executive. They had a free run under the UPA when the executive was weak. They have to retreat to their respective old dugouts now, but not without losing some of their own political, and more importantly, moral capital.

This is terrible for any democracy, most of all for one as diverse yet prone to majoritarian excess as India. This, when we have a strong executive after more than a quarter century, is just when we needed these institutions to be robust, and if they are close to their frailest in decades, they have themselves to blame.

A constitutional democracy such as ours is built around an astute division of powers, checks and balances. It is a good thing, therefore, that when an institution weakens, others fill in that void, but gently and with humility, accepting that this arrangement is unnatural and temporary.

Talking about the judiciary first, I would even accept the statement, made in the same week by one of our most respected Supreme Court judges (T.S. Thakur at the Kapila Hingorani memorial lecture in New Delhi) that when there is a governance deficit, the judiciary has to fill it. But I am not sure many judges had lately confined themselves to that.

Some of my earlier writings on this were provoked precisely because some of the benches had begun to show haughty arrogance. One told the government “we are getting angry”, another pulled up the Prime Minister’s Office, there were wholesale cancellations of mining leases and spectrum licences, taking the innocent and the guilty in their almighty sweep, and indeed the railroading of new judicial sinecures and authorities, including the National Green Tribunal, which has pretty much declared itself to be a top court and, given the sweeping orders it has been issuing (banish from Delhi all vehicles more than 15 years old), should be more aptly located in Tughlaqabad.

Also read: The courts do not have the ability, space, time, or powers to perform another institution’s role

It needs to be recorded that the judge who tended to get angriest with the previous government accepted a fine post-retirement appointment from this one. That the last CJI cadged a Raj Bhavan, and the current one praised the Prime Minister to the media. Now he is entitled to his personal views, as also to his choice of who to vote for. But think about it. What if a serving CJI thought a prime minister was an utter disaster, his government sucked, called the press home and said so?

I have to be careful not to digress into criticism of the higher judiciary, because that is not where I want to be headed. My concern is that the judiciary must remain strong, further strengthen its moral authority and not be vulnerable to political temptation or intimidation. The judiciary has shown weaknesses there. That is why a landmark constitutional amendment to restore the executive’s old precedence over the judiciary passed both Houses in less than 24 hours. And instead of a fight back now, we see praise.

It is interesting to note one significant fact here. The one top jurist/lawyer who attacked the constitutional amendment and promised to challenge it in the Supreme Court was also the one who has criticised the CJI for his public adulation for the Prime Minister now. He is Fali Nariman, the Great Old Lion of the Bar. Remember also that he has moral capital because he had stood up to the Emergency even at the cost of his additional solicitor general’s job at a young age.

The media finds itself in an even tougher place. When the going was good, and the government paralysed, we got used to hectoring, lecturing, accusing, not bothering to check facts, merrily adding zeroes to the size of scams, even inventing entire mythologies, like Adarsh land having been stolen from Kargil widows. Now we bend over to take selfies with the Prime Minister.

We are more inclined to go after Shashi Tharoor, who has not yet been charged with anything, while letting go of a saffron-clad clown who talks divisive, sexist nonsense while carrying murder and rape cases on his CV. But remember, we had said in 2010 that the media was suffering from hubris and would have to pay for it soon enough.

Also read: Conflicts behind conflicts in cricket

The NGOs and civil society had a free run under UPA, particularly in its second innings, walking all over the government, blocking every single new project and, where direct bullying did not work, seeking the courts’ indulgence.

The eventual banning of bauxite mining in Niyamgiri after many clearances, the on-off-on-off spectacle on Posco, blocking of Brahmaputra power projects, uranium and rare earth mining, Kudankulam and other planned nuclear power projects, raising of the Narmada dam height, ban on research in genetically engineered seeds, the activists won every single battle without a fight.

They overdid it to such an extent that now there is no popular sympathy left for them. On the other hand, there is wariness and fatigue. And once their reign ended, they haven’t displayed much spine either in their foundation-fattened bodies.

When Nandan Nilekani’s UPA was in power, its own favourite activists, even bureaucratic buccaneers in the Planning Commission, blocked his Aadhar at every step. Today, Narendra Modi is implementing it with gusto, under direct supervision of his office, and all opposition has disappeared. He has built the entire LPG cash subsidy transfer on Aadhar, and is proudly flaunting it in minute-long TV commercials.

Where are the naysayers hiding now? Occasionally a Greenpeace activist may make a show of defiance, but it makes no difference. The state has squeezed activist NGO funding and there is no sympathy for them among the public.

Freedoms, in any democracy, are a net product of statutory provisions and the social contract that institutions have with people in general. When the executive was weak, the judiciary, media and civil society grew too powerful, arrogant and obstructionist. Public opinion is now correcting that.

And remember, in any democracy, public opinion doesn’t work gently like homoeopathy. It moves more brutally, like a surgeon’s silverware. The old social contract having frayed, all three institutions, the judiciary, media and civil society, are left to fend for themselves now. All three, at least for now, seem to be in a crawl-when-asked-to-bend mode. That justifies our calling them the paper tigers that roared.

Also read: Justice with judiciousness