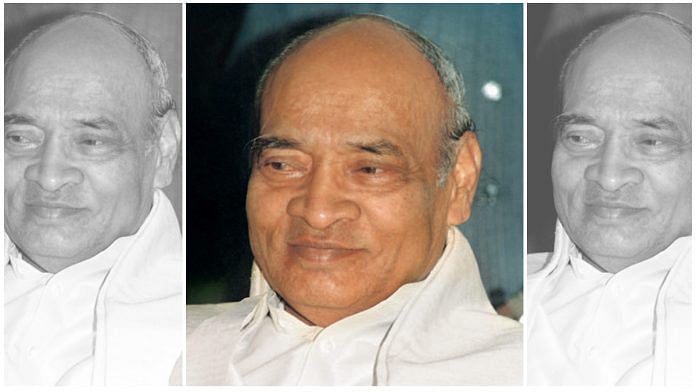

P.V. Narasimha Rao was the first serving prime minister I got to meet one-on-one in my reporting days and I had done very little to deserve that honour. In the course of an interview at Kabul in that winter of 1991, Najeebullah, the Afghan dictator, tapped me on the elbow and asked, through an interpreter, “I am told you are an important person. Can you tell Mr Rao one thing on my behalf?”

I was a mere reporter, I said, nobody takes me so seriously. But Najib said mere reporters were not sent to the Afghan war five times in a year and that in any case he had done his homework. Then he told me what he wanted conveyed to his Indian counterpart that he wouldn’t trust his own ambassador with. Salt that away for your memoirs and grandchildren, I said to myself. But, on my return, I did happen to mention this as a joke at a party to somebody close to Rao. The next morning there was a call from the prime minister’s office and an audience was offered.

Rao sat there, sipping his porridge. Rather slurping at it disinterestedly as grandfathers tend to do. I told him the story, the message, laced with many apologies. That I did not know what business I had to be there, that I had no idea why Najib had chosen me for this and not our or his ambassador or that I was possibly only being made a fool of. As a reporter, I said, I felt so awkward to be drawn into all this and would he please keep what I said always to himself? He smiled, patted his belly thrice, and said, what goes in there stays there for ever.

Rao was not one to take it all so lightly. He took lots of notes with a lead pencil and then gave me a long discourse on the Afghan problem, his truly masterly analysis on complexities that emerge when tribalism and ethnicity clash with religion in the absence of a well-defined nationalism. What the message was, and what Rao did, I must still save for my memoirs. But no other Indian prime minister, except Nehru, could have packed so much insight, so much intellect, in a 30-minute discourse on so complex a problem. And Rao wasn’t the last prime minister I met one-on-one.

A bit odd to write all this when all our editorial writers are celebrating his conviction, calling for an end to the style of politics personified by him, when not a hundred people turn up to watch him consigned to hard labour at 80, when the judge sees such good reason to ignore a foot-long list of serious ailments appended to his lawyer’s mercy plea and when even his very own Congress party is making lofty statements like, let the law take its own course. When was the last time this party used that line in response to the conviction of one of its own? Not when Mrs Gandhi (senior) was disqualified for electoral malpractices by Allahabad High Court (it was then called a minor traffic offence). Not when Sanjay Gandhi was produced in court to face so many cases of Emergency excesses and corruption. Many of those parroting the “let the law take its own course” line were then among the goon brigades shouting slogans and barracking witnesses and prosecution lawyers.

Also read: Why Congress has now woken up to own PV Narasimha Rao’s legacy

Rao was not the most accessible of prime ministers. He was also certainly the second most uncharismatic after Gowda. But he was always on the job. Much has been written about his shepherding of a very, very vulnerable India through the collapse of the Cold War, the opening up of the economy and the foreign policy, his very masterful marginalisation of Benazir Bhutto in her most virulent phase when Kashmir and Punjab were both on fire and a new one was being lit out of Ayodhya. This was when the Americans were constantly breathing down our throats, we needed IMF bailouts and the entire international human rights community had a single point focus: Kashmir. Who else could have decided to upgrade relations with Israel, but waited patiently for Arafat to come visiting New Delhi to make a formal announcement and get him to endorse it openly at a press conference?

Rao’s style was so hopelessly understated as to amount to self-denial, which is no virtue for a politician. But his method was thorough and effective. Cynicism may have been his personal style statement but what else could you have expected of somebody whose own party was unwilling to give him credit for what he was doing right? The biggest problem was, if he didn’t want to, he told you nothing, as if any extra word he spoke would give a national secret away. Are we doing better than before in Kashmir, I once asked him. “You see, we will do something, they will do something. What we get will always be a net of that, ” he said. Very helpful, I mumbled.

It was during the peak of the Kargil war that I dropped by one afternoon for a few words of wisdom from the old man. How would this Old Fox have handled a crisis like this? Would he have buckled under? Would he have escalated the war? Yet another lesson in Narasimha Rao’s art of crisis management. This is when he opened up a bit more on what he did the day Babri Masjid fell, when the news of the burning of Chrar-e-Sharif came, on how he swung the “settlement” of the siege of Hazratbal, on the way the rules of engagement were evolved in Punjab. Much of that I should let him save for his memoirs, or if he still keeps it all inside his belly, mine. But if among the few sympathisers in the courtroom on the day of his sentencing you saw K.P.S Gill, you can draw your own conclusions. Fortunately, not all men are so devoid of a sense of honour as the Congressman.

This is no political obituary of Narasimha Rao. Nor is it anybody’s intention to question his conviction or to raise questions on whether he deserves to go to jail or not. This is merely to underline this very fascinating situation of a man who achieved so much for the nation in five impossible years being so friendless on his way to jail and this is nothing to do with any moral outrage over his “corrupt ways”. The courts will hold him accountable for any sins he may have committed in terms of the law but, at a larger level, Rao is being punished by the entire middle class for keeping the BJP out of power for a full five years. Why else would it hate someone who gave them so much, through economic reform? Similarly, he is being punished by the Congress party for keeping the Gandhi family out of power. For daring to believe that he could lead the party, and keep it in power, whatever the cost, in the absence of an active Nehru or Gandhi. It is for this sin that the very party that should be so grateful to him now wants the law to take its own course and would celebrate his incarceration.

Also read: P.V. Narasimha Rao’s Kashmir policy was much more muscular than PM Modi’s