It is a sad but touching fact that nations and militaries tend to have stronger, more durable memories of their defeats than of their victories. Maybe because victories soon lose their euphoria in the inevitable economic aftermath of a decisive war, high inflation, arrogant, victorious establishments and so on. We have the post-1971 (Bangladesh War) turn of events in India, leading to 27 per cent inflation and the Emergency, as a sobering example. Maybe it is also because the pain of a military defeat sours our minds much more, leaving permanent scars that endure through generations. And it may just be that for generations, the loser wishes he could fight the same battle, the same war, again, this time with different results of course.

How else do we explain the wide interest now in the war with China, the anniversary of which is this very morning, exactly 50 years to the day that, on a freezing morning several kilometres north of Tawang, the Chinese attacked the Indian 7th Brigade at Namka Chu? (A tragedy described in great detail in Himalayan Blunder by J.P. Dalvi, who commanded this brigade and was taken prisoner, and later by Maj-Gen Ashok Kalyan Verma in his Rivers of Silence.)

It is also curious how, as nations and militaries reflect on campaigns as disastrous as these, they tend to forget the few moments of true military glory that they may have done well to cherish. Again, you can only guess why. Probably, the argument that besieges our collective conscience would be, what is the point of talking of one glorious charge, one incredible last stand here and there, when the end result was an utter disaster? Or could it also be that we are so overwhelmed by defeat and debacle that we tend not to take seriously any talk of something different, or maybe view with scepticism any story, any subplot that sounds a little bit different from the main script and its denouement? The 1962 War spawned more military literature and history than any other in independent India: it had to, as a defeat makes it very tempting for both, those accused of failure and the accusers, to explain. There has to be a reason why a bulk of the post-1962 books have focused on the eastern front, which was more or less a total rout.

There was the odd show of dogged defence, but everything was overwhelmed by the rout in Kameng, the self-destruction and flight of one of the proudest divisions of the Indian army, proudly called the Famous Fourth. Thag la, Namka Chu, Tawang, Dirang Dzong, Se La, Bomdi La (as you move north to south in what is now Arunachal Pradesh’s West Kameng district) are all imprinted in our national memory as distant, exotic stations on that awful trail from which our forces only fled, usually in panic and confusion, the strongest of them without firing a bullet or almost so. Much of the post-1962 literature, Neville Maxwell’s India’s China War, B.M. Kaul’s The Untold Story, B.N. Mullik’s Chinese Betrayal and D.K. Monty Palit’s War in High Himalaya, talks about the eastern front. Ladakh is mentioned in footnotes, or in passing.

Also read: India should not feel alone as it confronts Chinese Communist Party, US’ Mike Pompeo says

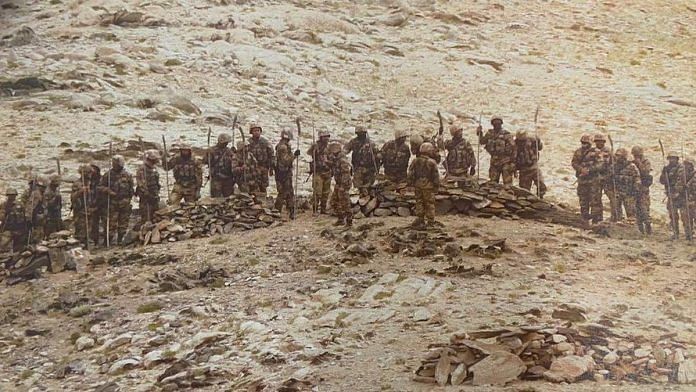

The front we read the least about is the one in the west. Surely, Ladakh did not see fighting of the scale, and incursions of the depth, seen in the east. But could it be, could it just be, that that is because our army fought that much better in the initial engagements with the Chinese? We now have Pranab Dhal Samanta’s scoop (The Sunday Express, October 14) on the still secret Henderson-Brooks Commission inquiring into 1962 to confirm that generalship in Ladakh was of a much higher order, and the results showed that. Yet, places in equally high (or in fact higher) Himalayas than in the east, Srijap 1 and 2, Gurung Hill, Daulat Beg Oldi, Spanggur Gap, Chushul and, most importantly, Rezang La, never made such an imprint on our minds, and have been erased through these decades.

Yet, these are places, usually between 15, 000 and 18, 300 feet in altitude that small detachments of the Indian army fought, sometimes to the bitter end. Yes, they did mostly get overrun in the end. But they were never disgraced, caused enormously greater casualties on the Chinese and probably dissuaded them from venturing deeper and crossing horns with larger bodies of the Indian army, particularly in Chushul Valley where artillery and tanks were both deployed a squadron of light AMX tanks having just been airlifted in a world record effort to Chushul airfield, one of the highest in the world.

Even an incorrigible military history enthusiast like this writer had nearly forgotten about what can only be described as a truly fighting frontier of 1962, until a tragic personal event took me to Rewari district in Haryana, 100 km south of Delhi. My old driver Ram Kumar, so much a member of my family, suddenly died of a heart attack and it took me to his village. He was an Ahir, as Yadavs are generally known in Haryana, and the Rewari-Mahendergarh districts are their homeland. It is then that a tiny memorial by the roadside in Rewari caught my eye. Lost in shrubbery and garbage (sadly) was the tiny column with the names of 114 soldiers of Charlie (‘C’) Company of 13, Kumaon regiment, who perished in the battle of Rezang La, engraved on it. But why a memorial to martyrs of the Kumaon regiment in Rewari? Because this was an Ahir company. Almost all those who died were from a small cluster of villages right here.

But you cannot appreciate the full story yet. Not until you know how many soldiers in the Charlie Company had stood that morning of November 18, 1962 (-24 degrees Celsius was recorded that morning) to defend Rezang La, a vital approach to Chushul Valley. It was 120, including the company commander, Major Shaitan Singh Bhati. Of these, 109 died fighting, five were wounded and taken prisoner by the Chinese. A few escaped later at night, in the confusion, as the Chinese licked their wounds. Among those who managed to escape and tell the tale was (then) Sepoy Ramchander Yadav, the major’s batman and radio operator, who was charged with concealing his valiant officer’s body so the Chinese wouldn’t find it, which he did successfully. He led a joint International Red Cross and Indian army expedition the following February to the exact spot where Shaitan Singh (awarded the Param Vir Chakra) lay between two boulders, buried by him under snow, a patch of frozen blood and a white mitten kept as a marker. Last Sunday, Ramchander, and (then) Sepoy Nihal Singh, who manned the LMG (light machine-gun) with the major’s party, was the last man firing from his company headquarters until a Chinese MMG burst went through both his elbows, was taken prisoner and escaped despite his fresh wounds, agreed to come to Rewari to tell me the story of those incredible five hours 50 years ago. It is the first time I am making such a pitch, but you will understand why. So please catch their first-person accounts on NDTV 24×7’s Walk the Talk, in a special two-part conversation this evening, and the following Saturday.

Many have compared this battle, in terms of the sheer doggedness and last-man-last-round spirit of this company to the other great and losing last stands in military history: Thermopylae, Saragarhi (involving our own 1 Sikh), Waterloo, Inchon River, and so on. But for a long time, this story was not believed. Both these veterans tell me how, for years, they were ostracised by villagers wondering how they had escaped while the rest died. The late General Sundarji had once lectured me, on a drunken night at a Track-2 conference in Salzburg in the summer of 1994, on the Indian army’s remarkable blessing of small unit cohesion. You look at the casualty list of Rezang La to understand what he means. Most men in the Charlie Company were neighbours or relatives. In one remarkable instance, two brothers and their sister’s husband died. Only the company commander was a Rajput (from Jodhpur). His name was Shaitan Singh, but he was a devta, says Ramchander. He said, don’t call me Bhati, call me Yadav. He also told them, as the overwhelming dimensions of the Chinese attack became evident, that none of them was to even think of anything but fighting. Because their orders were to hold out for as long as possible.

Also read: Modi’s bid to sway China’s Xi with personal outreach was a big error. India’s paying for it

I would be the wrong person to describe the battle or what followed. The finest research, and the most accurate account of the battle is to be found in Amarinder Singh’s (yes, the former Punjab chief minister) remarkable book Lest We Forget, which dedicates its entire fourth chapter to 13 Kumaon and Rezang La. It wasn’t until Indian patrols returned the following spring that they found evidence that confirmed the stories of the three immediate survivors: almost all the bodies (103 in the first instance), frozen weapons in hand, all ammunition clips empty, some inside their trenches and many outside, cut down by multiple bullets and bayonets in hand-to-hand combat with the attackers. Amarinder’s book has published some of these stirring pictures. And Chinese casualties? The memorial column at Rewari says 1, 300 dead. Amarinder’s estimate, based on the army’s detailed inquiries with villagers and herdsmen who saw the Chinese take away their dead and wounded over several days, is between 500 and 1, 000. Ramchander says he saw Chinese bodies heaped like fruit in a mandi. And to those who doubted his claims, he has had the same answer since his first debriefing at his headquarters: You put me at 18, 300 feet with an LMG and try assaulting me from 5, 000 feet below and see how many I kill.

The defence of Ladakh was a more glorious chapter of 1962 but has remained largely unacknowledged. One of India’s finest war movies, Haqeeqat, was built around the battle of Rezang La with a little bit of local romance, etc thrown in. It is also no surprise that while most generals involved in the east faded away in ignominy and disgrace, Brigadier T.N. Raina (Tappy), who so resolutely led 114 Brigade in Chushul (including 13 Kumaon), went on to become one of our most decorated soldiers (Maha Vir Chakra) and army chief. Even now, at most parades, you might hear a stirring composition from the army bands called General Tappy. And the decrepit, rotting memorial at Rewari may see better days still. After all, 13 Kumaon is now posted at Kota, not far away, and has decided to help the local citizens’ committee spruce it up and start a proper memorial ceremony.

Postscript: Do I have a personal wish on this sad anniversary? Yes. It is to be given a sand-blaster, a spray-paint can and an hour of amnesty. All I want to do is change the name of the avenue in central New Delhi named after Krishna Menon, the man primarily responsible for not just the humiliation of 1962 but also the loss of so many lives. A political system that still names avenues after an obstinate, autocratic disaster like him (whatever his filibustering brilliance), and that too, the avenue leading to its military headquarters, needs to introspect and correct its view of history. Or somebody pick up that sand-blaster and spray paint and rename it after Major Shaitan Singh or 13 Kumaon.

Also read: After Ladakh, India & US need deeper economic relationship, not just strategic