It may be difficult to conclusively say today who that mole was, but certain facts are possible to ascertain. Are there any minutes from the Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs that talk of a decision to go ahead with the tests? Similarly, are there any CCPA/CCS/PMO minutes of any kind of a decision to cancel the tests and the justification for doing so?

This is the very bureaucratic, brahminical Bharat Sarkar. This is not Pakistan or North Korea where scientists can be ordered by a strongman on the phone to go ahead and do such things, or pull back. This establishment loves bureaucracy, the written word, instructions, authorisations, etc. Were any ‘materials’ moved to Pokharan?

You could ask why the UPA government would do anything like that and expose the lily-liveredness of a Congress government? But the same records were available to the NDA also for six years. You think they did not look through these, searching for evidence that they had shown steel ó alloyed with plutonium? It would have worked a great deal better than India Shining in 2004 and would have been a devastating argument in the post-Kargil mood of 1999. Talk of the mole had preceded the arrival of the NDA in power by nearly a year. So why did nobody make any effort to look for him? Or at least somebody should have enlightened the nation on how the Congress under Rao had let them down so shamelessly.

There are several reasons why even people who would not normally lie do not like to speak the truth. One of these is that the truth usually is a terrible enemy of conspiracy theorists. And the truth in this case most likely was that there was no real plan to test and thereby no cancellation under pressure and also no mole. But there was the scent of a conspiracy. The Americans were obviously made to believe tests were going to be held, which resulted in Strobe Talbott making an unscheduled visit to see Narasimha Rao in Washington to convey a firm message from the President to cease and desist. But my guess is Rao heard him out most gravely and then had a big laugh later.

You ask any of the players in 1995 and you would know that there was talk of a test, but nothing had reached the stage where satellites could have picked up anything really substantive. There was, however, so much noise over the tests in the top establishment that it would have been impossible for the regular South Block watchers in the diplomatic corps not to pick up some of it. Certainly, many of our own journalists had, which is quite in contrast with the situation during the weeks preceding both 1974 and 1998, when real tests were being planned.

True to his style, Rao had involved several people to carry out two different sets of studies. One was to assess the political and the other the economic consequences of the tests. This was less than six months before elections were due, and I believe his analysis was that sanctions following the tests would be vicious. Kashmir was on the boil and India was already under extreme pressure from international human rights organisations. The political analysis he received convinced him this would lead to massive internal hardships and rise in prices, which in any case peak around the pre-monsoon months. Things might get so bad, he told his closest advisors, that his party may not even field him.

Even more significant was the analysis on economic consequences. India was not as strong economically in 1995 as in 1998. We were just recovering from the near-bankruptcy of 1991 and were still greatly dependent on multilateral lending institutions.

In view of these realities, he had decided a long time before alarm bells rang in Washington that he was not going to conduct the test. Tests, if at all would be conducted when he returned to power. And if Chandraswamy had convinced him that he had sorted out the gods and there was no ‘if’ to his re-election, I wouldn’t know because I did not have a mole in the godman’s durbar.

More important is the fact that besides the doubts on the political and economic implications, even the scientists were not ready. In 1995 it was impossible to imagine India could ever hope for two more shots at testing.

Finally, here is one more important fact to consider. The scientific establishment had been successful in concealing its plans in 1974 and 1998. How could they have got caught in 1995? The truth is they know exactly when the satellites make their passes and how to dodge them. Similarly, you’d presume, they’d also know how to get ‘caught’ if they wished to.

The desperate need to score political brownie points apart, we do ourselves great disservice by promoting the idea that we are somehow a leaky, weak, traitor-ridden establishment where spooks and moles sell the national interest to the highest bidder. The truth is, when it comes to keeping secrets at the top, and running a few vicious intrigues with our adversaries, this gang is more formidable than most. Not only can they do it with a straight face, they can also sit tight without falling to the urge to exult. Because the game is still on, and many of the players are still the same.

Last chance for Arunachalam

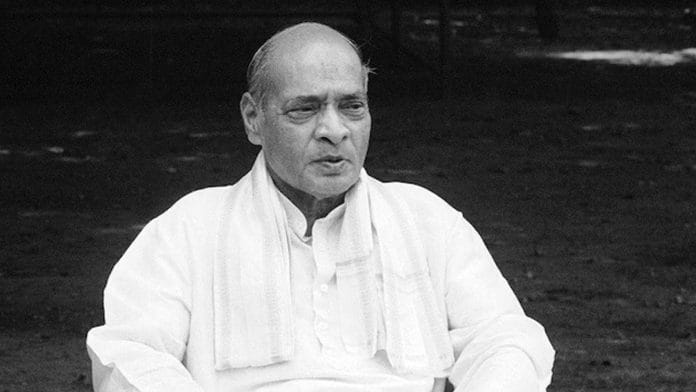

Last week I wrote in passing about the completely unnecessary suspicions over the abrupt departure of V.S. Arunachalam, the then DRDO head to teach and research at Carnegie Mellon. One TV channel even emphatically named the poor man as the mole. Nobody who knows Arunachalam would easily buy that.

One of them is Arun Singh, no stranger to our defence establishment. It was, in fact, an interesting friendship between Arun Singh, then the closest Rajiv Gandhi confidant, Arunachalam, Gen. Sundarji and the then navy chief, Admiral Tahiliani, that gave an unprecedented push to India’s military modernisation in the late eighties.

This week I received a surprise phone call from Arun Singh, obviously shocked by Arunachalam’s name getting dragged into this mess. He told me the truth behind his seemingly ‘abrupt’ departure. He was back in the government as the head of Committee on Defence Expenditures (CDE) in the V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar governments and advised Arunachalam that he had been the head of DRDO for too long and it was not good for him. It is then, Arun Singh tells me, that the scientist told him he had a position available at Carnegie Mellon, which has one of the finest labs in his field. “We thought this was a perfect place for him, as he could also work with Dr Raj Reddy who is an icon in the world of robotics and high tech. This would have also given his children an opportunity to study free in one of the best schools in the US because Arunachalam, as a faculty member, would be entitled to it”. Singh says the problem was, how to convince the prime minister to let him go and who was to be the new head of DRDO. Arunachalam met Narasimha Rao several times to convince him that he needed to leave and that he would not be missed because there was a very logical successor, albeit a bit old. That rather ‘old’ person was none else than President A.P. J. Kalam!

So here is one more nail in the coffin of conspiracy theories, if one was still needed.

(This piece was first published in 2006)