Bengaluru: The hero singing in search of a lover is as much at risk from the lurking villain as the heroine drawn by his voice to trace him: This finding about insect behaviour from a recent study by the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, turns conventional wisdom on its head, and promises to change the way insects are studied.

According to the study, published in the journal Evolutionary Ecology last month, the males of an insect species who call out to females for mating don’t face any greater danger of drawing the attention of a predator nearby.

Both males and females attracted predators with equal probability, the researchers found.

This is significant because the one thing scientists always assume when they study mortality, life cycle, habits etc is that “signalling males” are often lost to predators.

This study suggests that there is no increased risk to the signalling partners, which means mating behaviour can totally be excluded as a factor in such studies.

“In mate-searching literature, signalling is considered risky even without comparing it with how risky responding to signals can be,” Viraj Torsekar, lead author of the study, told ThePrint.

Torsekar and his fellow study authors, Kavita Isvaran, and Rohini Balakrishnan, are all researchers at the IISc Centre for Ecological Sciences.

“We believed responding to signals would be as risky as signalling, if not more. This prompted us to investigate this question in a system that allows us to estimate the risk at multiple scales at which predators and prey interact,” Torsekar added.

Also read: US drug authority warns Indian homoeopathy firm after it finds insects & rodents at factory

The mating dance

A common scene in most nature shows narrated by English natural historian David Attenborough is the male of a species building nests or performing elaborate dances to get a female’s attention and consent.

Which sex invests more time and effort in attracting a mate depends on how much benefit it gets: Given that males generally reap greater benefit from multiple matings by spreading the seeds, and females are grounded by the process of gestation and rearing, males of most species take the lead in attracting a mate.

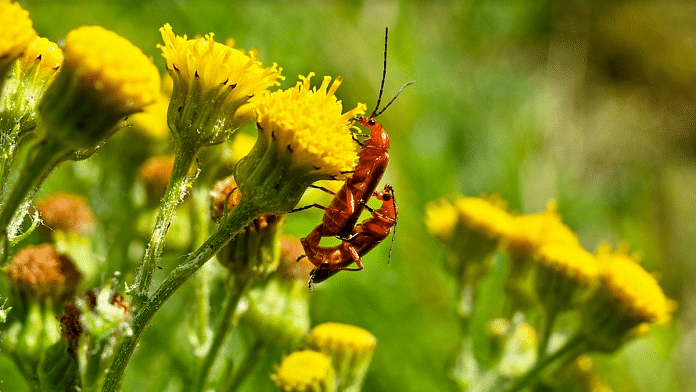

In some species, however, when males issue the calls, females move towards them in response to the signals — with the group of insects comprising crickets, locusts, and grasshoppers falling in this category.

This expenditure of energy and effort on part of the female is theorised to be because of potential benefits for her: The male often burrows, which the female can then use for shelter after mating.

It was this group of insects that were studied by the IISc researchers, with the scientists using four categories of tree crickets for their study: Calling males, non-calling males, responding females, non-responding females.

The green lynx spider, known to prey on tree crickets and honeybees, was roped in as a predator.

These spiders can detect both sound, which produce vibrations in the air, and movement, through the air-flow-sensitive hairs present all over their bodies, which helps them sense the mate signalling as well as the one responding.

Sound & movement

The team performed their field surveys in the Chikkaballapur district of Karnataka and in an enclosure inside the IISc campus.

They studied and calculated three aspects of the tree cricket’s relationship with the green lynx spider: The probability of the two species occurring in the same bush, the probability of the two encountering one another, and the probability of the spider eating the cricket.

As part of the study, the researchers recorded the sounds made by crickets and then played them in the wild to attract spiders, to deduce whether the spider was indeed the primary predator for the tree cricket.

The spiders were kept hungry for varying periods of time to observe if they showed preference for a sex or a method of tracking. Predator and prey, one of each, were typically released into the study field together, at various combinations of times, distances, sex, and hunger levels.

The findings were counter-intuitive to accepted wisdom.

“On the same bush, the probability of encountering a spider was similar between the predominantly sedentary calling males when compared with mostly mobile responding females and non-calling males,” the researchers wrote in the study.

“Similarly, encounter probability with a spider was similar between mobile responding females when compared with non-responding females and calling males,” they added.

According to the researchers, one of the probable reasons for this is that both calling and non-calling members of a species take similar measures to avoid predators.

“We found that acoustically signalling males carry the same risk from predation as silent responding females,” said Torsekar. “Predation risk of communicating individuals is similar to that of non-communicating individuals in both sexes,” he added.

The study also found that the overall risk of predation due to mating is low.

Also read: Plants can ‘hear’ pollinators, and a lonely snail goes extinct