New Delhi: Using genomics and other molecular biology techniques, an IIT Jodhpur research team has recently published a paper stating that unknown genetic factors are responsible for the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae, a bacteria that causes infections in hospitals.

Further studies are underway into the potentially new mechanisms responsible for the bacteria’s virulence and the response of mutants.

The study was led by Dr Shankar Manoharan of the Department of Bioscience & Bioengineering at IIT Jodhpur and performed in collaboration with scientists from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, AIIMS Jodhpur, and Vellore Institute of Technology.

The findings of this research have been published in the journal Microbiology Spectrum, authored by Dr Manoharan and other scholars.

A pathogen that has made its way to the World Health Organisation’s priority list — Klebsiella pneumoniae — is a major cause of diseases such as pneumonia, meningitis, UTIs, diarrhoea, and even bloodstream infections, causing ‘nosocomical’ infections. These are mainly acquired in person-to-person contact from hospitals. It is more likely to affect those with a weakened immune system.

The bacteria is also notorious for being resistant to drugs.

Emphasising on that, Dr Manoharan said in a press release, “One of the ways in which Klebsiella pneumoniae escapes the body’s immune system and antibiotics is by producing an extremely sticky and viscous protective covering (hypermucoviscosity) around itself.”

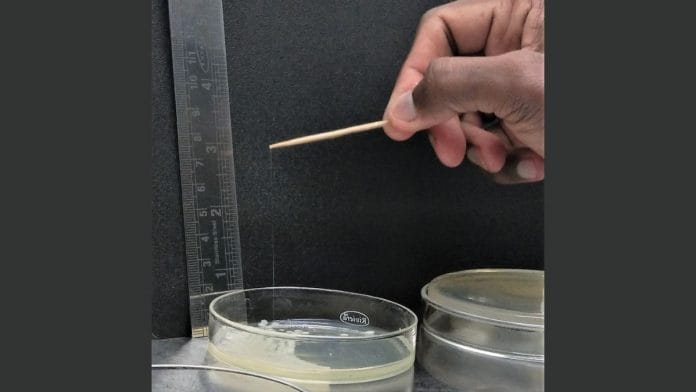

To test its potency, the team of researchers employed a string test to identify the hypermucoviscosity of the bacteria. In this process, a bacterial colony growing in the laboratory is touched with an applicator, and then lifted away from it. If the sticky string appears to me 5mm or longer, the bacteria is considered hypermucoviscous and highly virulent.

Studying a strain of the bacteria called P34, which they had obtained by isolating it from a cystic lesion of a 67-year-old female patient at a hospital in Jodhpur, a 65mm string was produced. This conclusively proved the bacteria to be hypermucoviscous and hypervirulent.

But after a phenotyping and genomic analysis — methods for analysis of biochemical reactions, the usual rmpA, rmpA2, rmpC, and rmpD genes that are commonly associated with the bacteria, were not found in this strain.

This points to the presence of other unidentified genes in the bacteria, making it resistant to a human’s immune system and to antibiotics. This prevalence of undiscovered factors contributing to hypermucoviscosity, is the main finding of the study.

The capsule or sticky substance that surrounds the bacteria is what mainly contributes to the potency of the virus, and even defies a human’s bodily immune response. The capsule protects the bacteria from opsonophagocytosis and serum killing — which are innate defenses against microbial infections. Thus, it renders one’s immune system ineffective.

Significantly challenging the medical and scientific community all over the world, the high virulence and antibiotic resistance of the pathogen has made the management and treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae a major hurdle.

Previous studies on K. pneumoniae mutants have determined that the bacteria is rendered avirulent owing to certain mutations, but those studies were based on mouse models.

Dr Manoharan said: “We are currently studying these mutants and disrupted genes to explain the potentially new mechanisms behind this unusual sticky and viscous covering of Klebsiella pneumoniae P34.”

Also read: No animal testing, human volunteers—how new-age ‘in silico’ trials will make drugs cheaper