New Delhi: The Ganga river is drying up at an unprecedented rate, and it’s going to impact water and food availability for over 600 million people. A new study by the civil engineering department at IIT Gandhinagar has found that from 1991 to 2020, the Ganga’s stream has declined rapidly, with an intensity that is 76 percent higher compared to the severe drought in the 16th century, the closest similar event in history.

The paper, published in the PNAS Journal on 22 September, said that even normal climate variability of the past millennium cannot explain this recent drying up.

“This could probably be the first ever such study conducted for the Ganga – we have taken (streamflow reconstruction) data from the last 1,300 years to reconstruct this history,” said Vimal Mishra, the author of the study and a professor in IIT Gandhinagar’s civil engineering department.

The paper reconstructed the Ganga river’s streamflow, its intensity, and the years in which it declined and by how much, to present an idea of how the river’s course has changed over 1,300 years from 700 CE onwards.

They found that compared to the overall average streamflow from 700 CE to 2012 CE, Ganga’s streamflow was very low specifically from 1991 onwards– “drying from 1991 to 2020 is unmatched in the past millennium”.

In fact, frequent droughts and low monsoons pulled down Ganga’s stream intensity so much in the last three decades that they impacted the average streamflow of the period between 1951 and 2020.

There are a lot of reasons for this decline, but the main ones are droughts and low monsoons, said Mishra.

“The entire Ganga basin in the plains has suffered due to very low rainfall over the last 30 years, and it is but obvious that it would impact the river’s strength.”

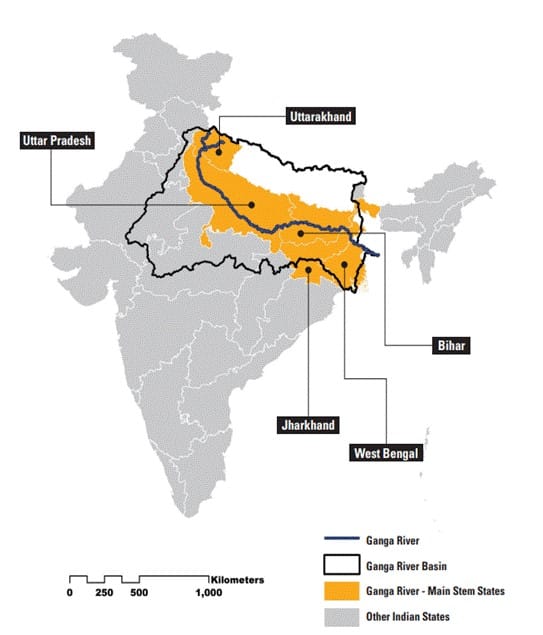

The Ganga–one of India’s longest rivers–spans over 2,500 km from the Gangotri glacier in Uttarakhand, through Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and even Bangladesh before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. While it is originally a glacier-fed river, Mishra explained that glaciers are not enough to sustain the river’s flow throughout the year.

“If you see, the glaciers only keep the river going for a few months in the pre-monsoon season like April and May,” said Mishra. “Even then, it is only upstream near the hills where this effect is seen. The rest of the river needs a proper monsoon to survive.”

Given this need for rainfall, the data by the IIT Gandhinagar researchers showed that the Ganga River Basin (GRB) saw a 9.5 percent decline in annual mean rainfall in 1951-2020, as compared to the previous years. Some parts like the western basin saw up to a 30 percent decline. Overall, from 1991 to 2020, the GRB witnessed 15 drought years, and 20 years with below average streamflow of the Ganga.

“This decline in rainfall obviously impacted groundwater storage too, and that further reduced the stream size of the Ganga,” said Mishra. “But one of the main culprits is also anthropogenic actions like irrigation and excessive water usage along the basin.”

Also Read: The trinity that failed women at Maha Kumbh. Holy, unholy, and the algorithm

Human actions & climate change

The paper explained that there were other stretches in the 1300-year-long period they studied when the Ganga experienced lesser streamflow because of droughts or other historical events. The Bengal Famine of 1,770, and other recorded famines of the 1,800s also showed up in the Ganga’s river basin data, not to mention years when rain was bad because of climatic conditions.

However, Mishra says in the paper that the drying up from 1990 onwards could not be explained by just normal climate conditions.

“You need data from a long period to be able to truly tell when a change is new or unprecedented and falls outside the normal curve,” he explained. “And this drying up in the last three decades is exactly that. It’s not just the climate, it’s human actions too.”

The Ganga river basin waters 47 percent of India’s entire population and is the second most water-stressed basin in the country. According to data from PIB, the basin covers 27 percent of India’s geographical area, and 65.57 percent of it is used for agriculture.

“Human actions and human-led climate change are definitely both factors contributing to the Ganga’s drying up. The excessive agricultural and other usage of water, as well as anthropogenic factors that contribute to global warming directly and indirectly affect Ganga’s flow,” said Mishra.

The paper said that while future projections of rainfall indicate higher precipitation in the future, climate change could still impact the actual rainfall levels. The authors say that water management and conservation strategies should be developed in response to this information about the Ganga’s drying up.

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: Is Ganga really self-cleaning? Here’s what science says