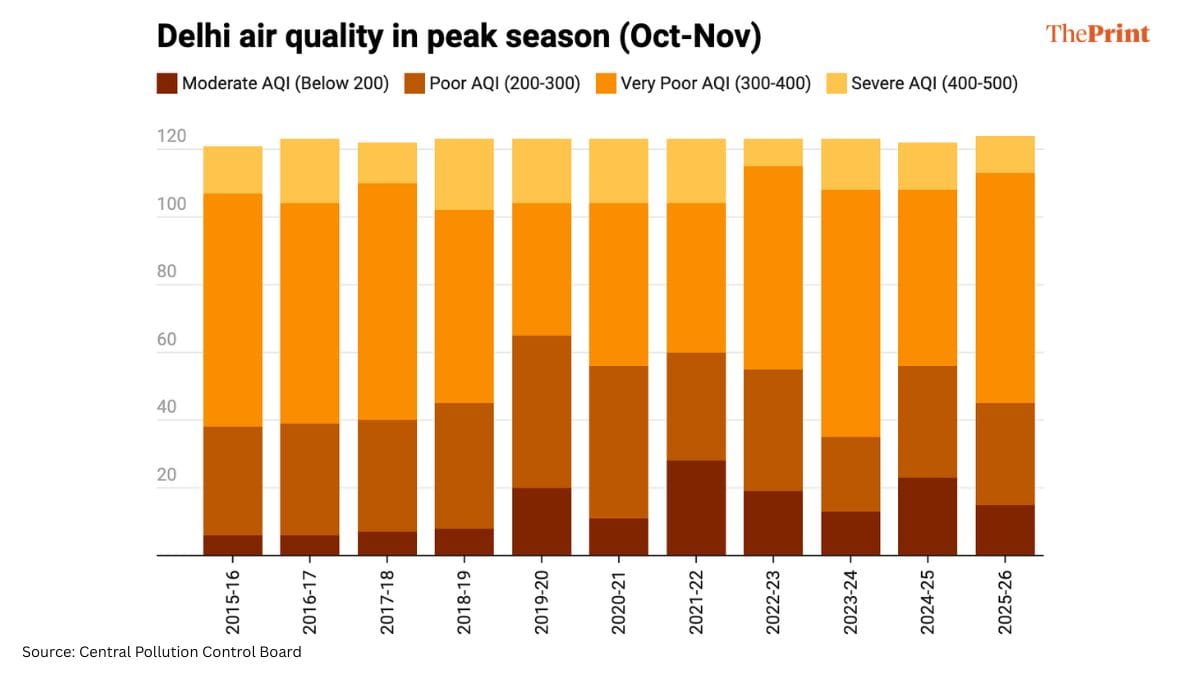

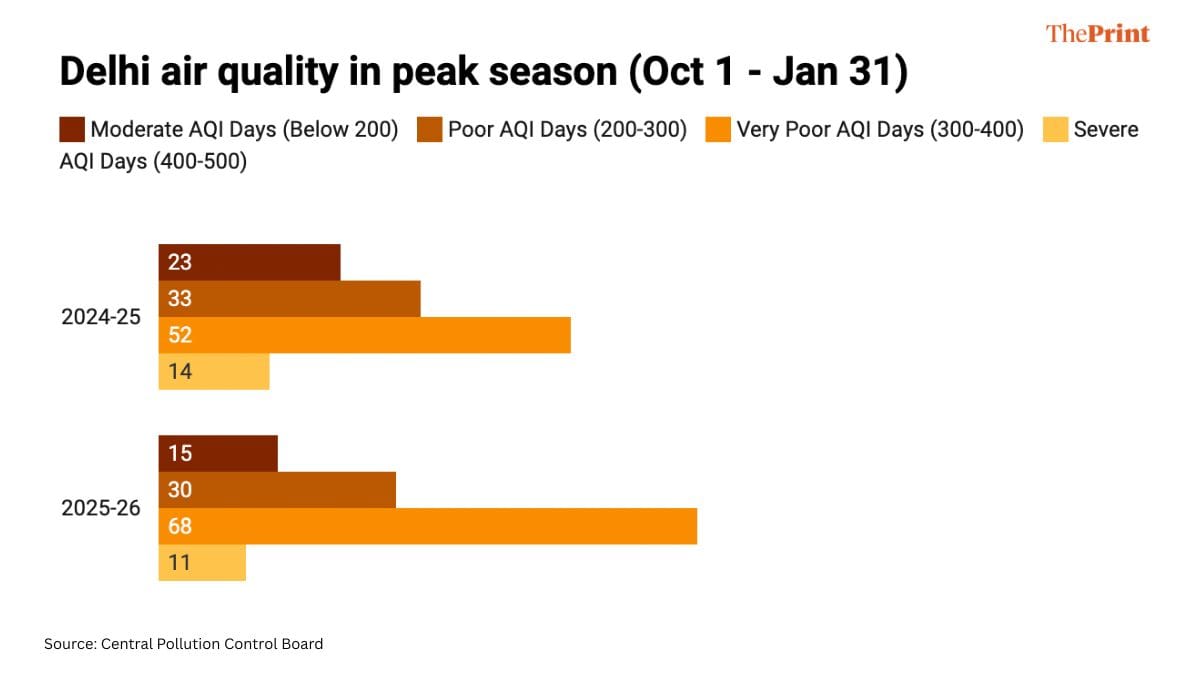

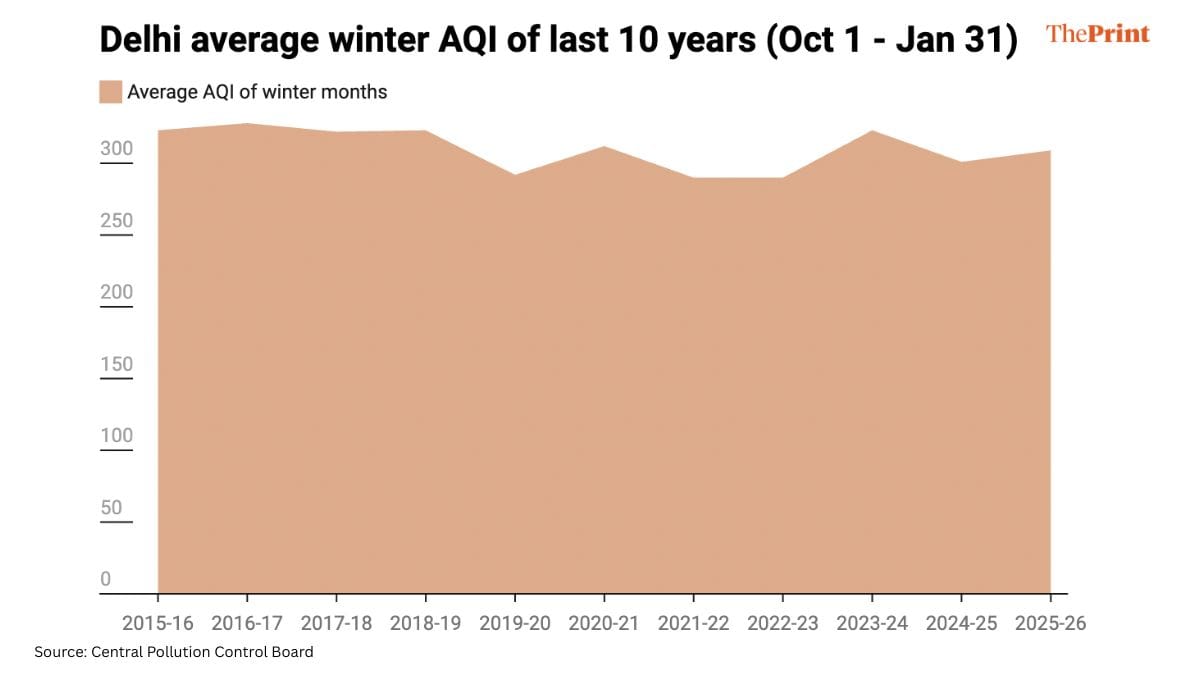

New Delhi: In 2015-16, Delhi had 69 ‘very poor’ air quality days, with AQI between 200-300, from October to January. Ten years later, after the imposition of GRAP or other pollution measures, there were 68 ‘very poor’ air quality days.

This means that over a period of four months, from 1 October 2025 to 31 January 2026, Delhi citizens experienced ‘very poor’ air quality every other day.

After ten years of air quality legislation, firecracker bans, the imposition of Graded Response Action Plans, and State Pollution Action Plans from 2015 to 2026, are there measurable changes in Delhi’s overall air quality?

ThePrint looked at average AQI and average particulate matter (PM) 2.5 numbers in the winter months of October to January in the last ten years to answer this question. We also analysed historical sources of air pollution—farm fires count, transport sector growth, and diesel and petrol usage—to chart Delhi’s changing pollution profile.

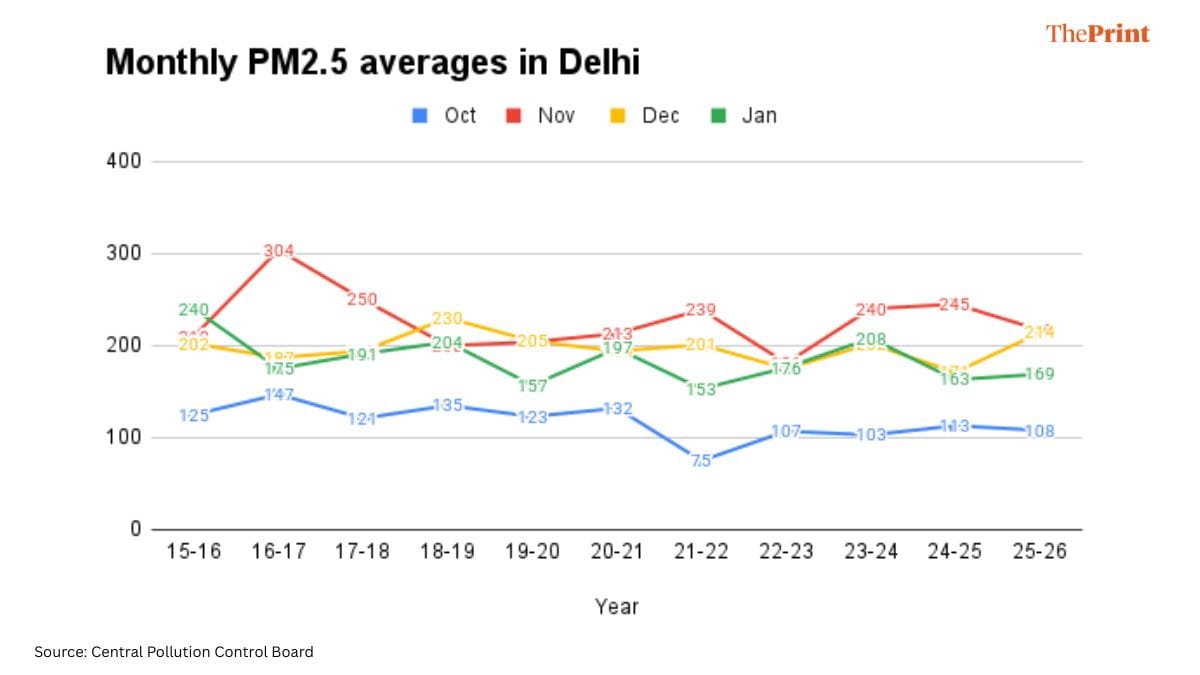

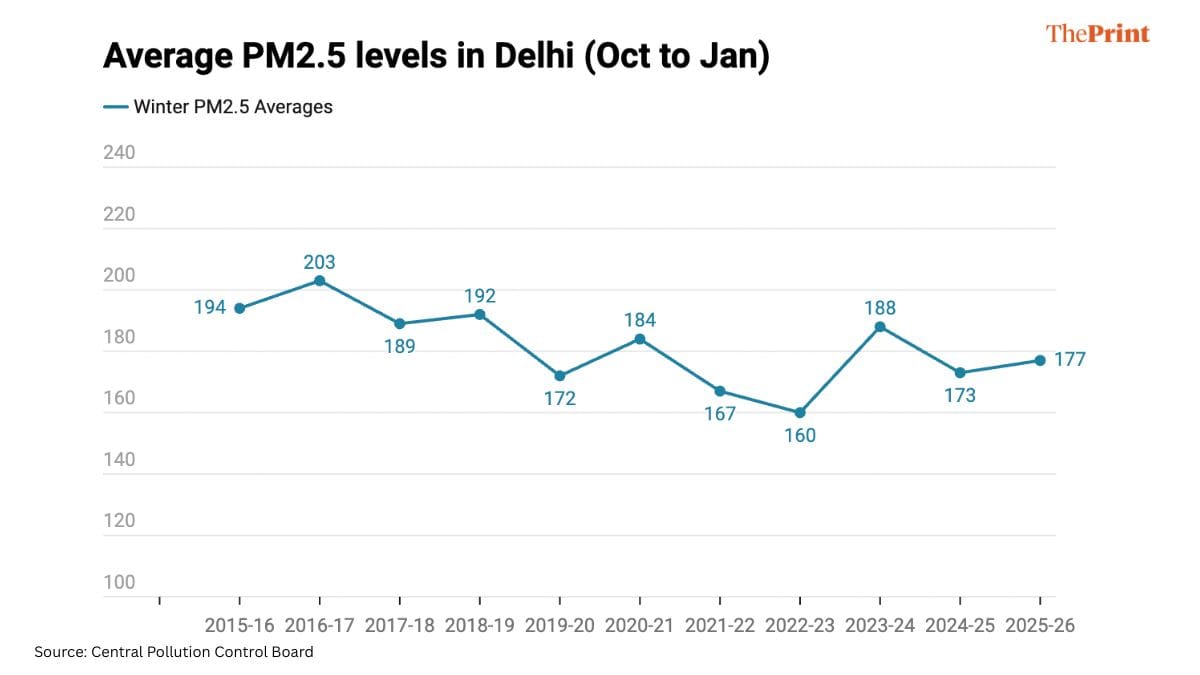

The results show that there is no sustained, long-term improvement in Delhi’s air quality. Both overall AQI and PM2.5 averages for the winter months in the last ten years show stagnation and even recent increase 2024 onwards. The reasons behind this are complex.

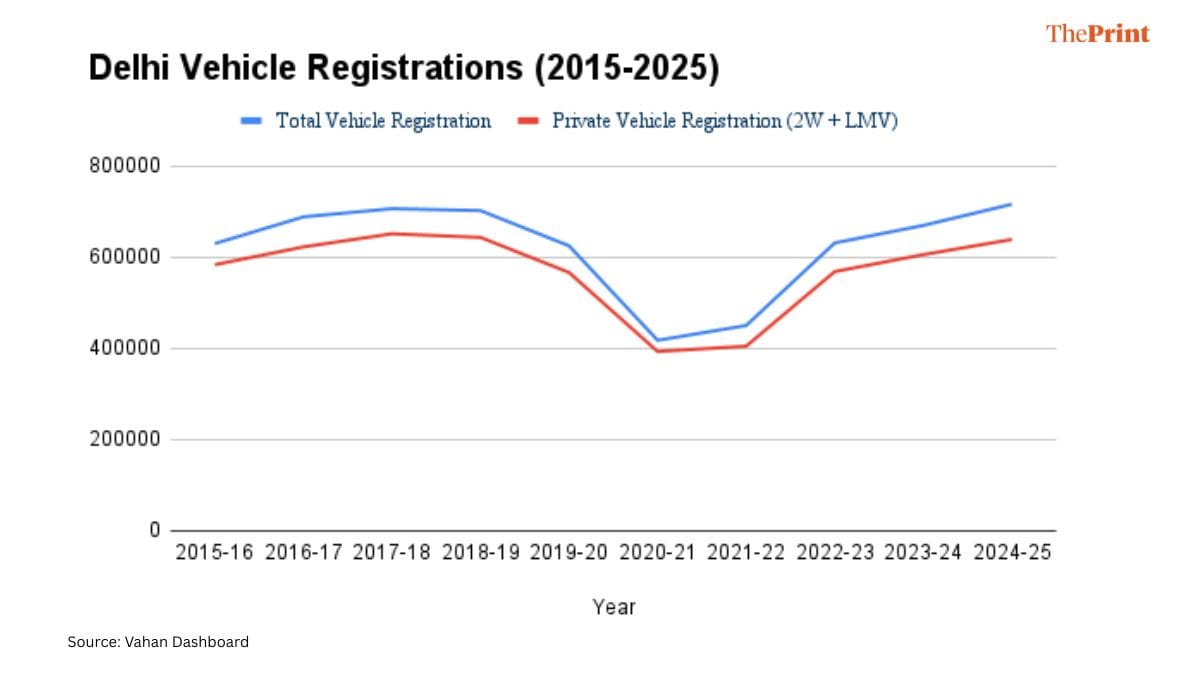

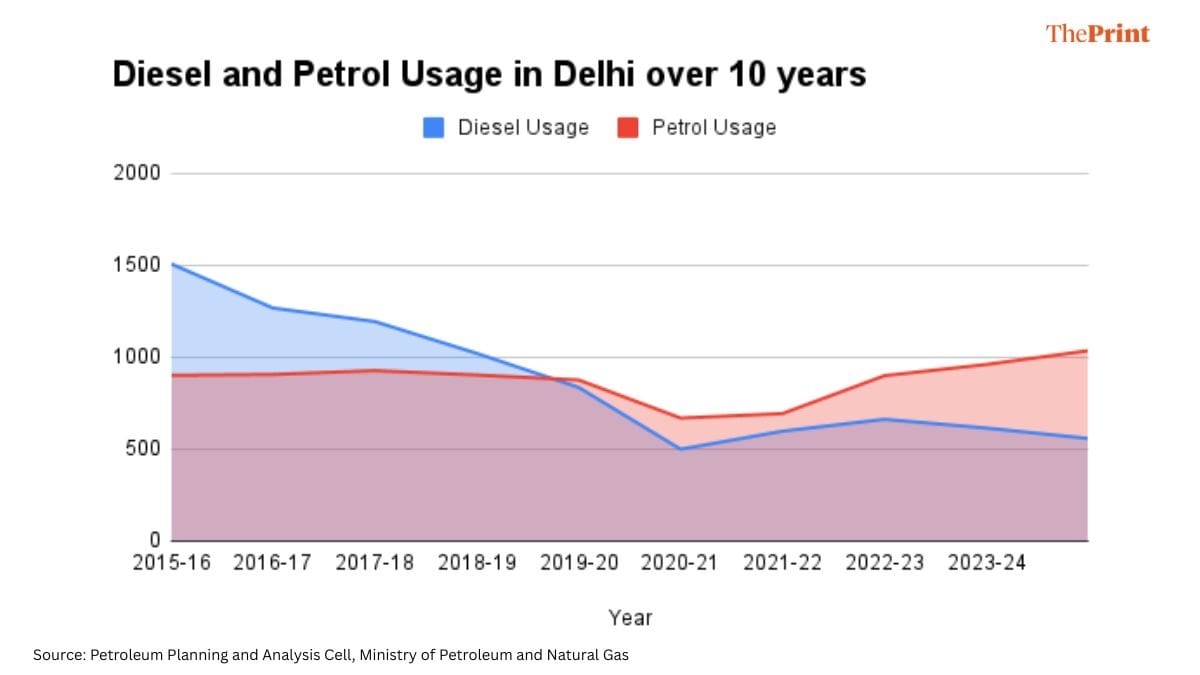

Even as farm fires and diesel usage have declined considerably since 2015, private vehicle ownership and petroleum usage have increased.

Most importantly, severe AQI spells as well as peak pollution episodes have remained a consistent presence across the last ten years, meaning that Delhi citizens are exposed to poor quality air for the same period now as they were ten years ago.

“Ten years is sufficient time to see a change in air quality, if you have the right policies,” said Chandra Bhushan, CEO, iForest, an independent non-profit environmental research and innovation organisation. “Beijing did it. And if we had implemented the right course of action, we could have done it too.”

Delhi’s air pollution is caused by a combination of factors like transport, construction and biomass burning. In the winter months, it is exacerbated due to lower temperatures as well as seasonal factors such as stubble burning in the fields of Punjab and Haryana, and Diwali firecrackers. But data shows that the reduction in the observable farm fire counts in Punjab and Haryana over the last five years has not led to an equal reduction in AQI levels in Delhi.

The contrast was most starkly visible this year, with Punjab and Haryana seeing the lowest number of farm fires in the last five years. With the floods in Punjab in August, experts had estimated that farm fires would reduce drastically, thus contributing to less pollution in Delhi. Official numbers from the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) show that there were only 6,080 farm fires recorded in the paddy harvesting season of 2025, the lowest till date.

However, Delhi’s air pollution actually rose this year compared to last year.

The total number of ‘very poor’ air quality days during the winter pollutant season in 2024-25 was 52, but this year it was 68. Also, the number of ‘moderate’ air quality days in the same period (below 200 AQI) reduced from 23 last year to 15 this year.

With a reduction in farm fires, the reason for Delhi’s high pollution shifts to other factors, mainly transport and fuel consumption.

There’s been a steady growth in the number of new vehicles registered in Delhi over the last decade, with over 6,00,000 vehicles every year except during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ninety per cent of this growth has been in the two-wheeler and light motor vehicle categories, meaning private passenger vehicles like cars and jeeps.

Even with policies such as the mandatory shift from BS-IV to more efficient BS-VI fuel standards that happened in 2020, the city’s fuel consumption has not seen a downward trajectory.

Diesel usage reduced significantly since 2015, led by a reduction in diesel-run cars and generator sets due to policy changes. But this has been replaced with a growth in petrol usage, as more and more passenger cars opt for petrol.

“Even schemes like the National Clean Air Programme have failed because they couldn’t reduce the absolute emission loads across cities and could not improve the public transportation infrastructure to a level where people would shift away from high private vehicle ownership,” explained Sunil Dahiya, Founder and Lead Analyst at Envirocatalysts, which analyses air quality as well as activity and emission data.

It’s why Delhi’s average winter air quality graph over the past 10 years is not linear; there are certain dips and spikes observed every year. But when all factors are taken into account, one thing is unmistakably clear—Delhi’s average winter AQI has remained firmly in the ‘poor’ and ‘very poor’ range since 2015, not moving below 290-330 AQI.

The 2025-26 pollution season

On 2 September 2025, Delhi had an average AQI of 52 — which is the closest it got to ‘good air quality’ (between 0-50 AQI) before the winter plunge into toxic air.

In the 122 total days of winter from October to January, there were 15 ‘moderate’ AQI days this year. Even these ‘moderate’ AQI days were concentrated in the first two weeks of October, after which the AQI in Delhi never went below 200.

The first pollution ‘peak’ was observed in the days following Diwali, with four continuous days of 300+ AQI levels, indicating a descent into ‘very poor’ air quality from 20 to 24 October. The real peak, though, came in November with 24 continuous days of ‘very poor’ AQI above 300, from 6 to 29 November.

There were also two intense spells of three continuous days of ‘severe’ AQI above 400—once in mid-November, and again in mid-January.

While peak spells of ‘severe’ AQI do occur for days together in Delhi, they usually take place in November or early December. This year was the first time in ten years that a pollution peak occurred as late as January, hinting at the changing pollution profile of Delhi.

The monthly averages of PM2.5 levels also show this change. While November is usually the month with the highest PM2.5 in the air, a few years in the last decade show that PM2.5 peaks are extending to January too.

“It is worrying to see that this year, despite the reduction in stubble burning, we saw an increase in bad pollution days,” said Mohan George, clean air consultant for Centre for Science and Environment. “It clearly means that we need to take a hard look at our policies and how we’re implementing them.”

Meteorological conditions also play a role in the extent of pollution in the city, according to DS Pai, senior meteorologist at the India Meteorological Department. He explained how low wind speeds and high humidity often lead to more air pollutants being trapped on the ground.

“There are a lot of factors at play, but one reason for short but severe pollution spells could be humidity and the role of Western Disturbances,” explained Pai. “We often have a dry winter with Western Disturbance activity limited to the early part of the season, but this time we saw rainfall even in January.”

History of pollution action

In 2015, Delhi’s air pollution crisis made national headlines when three toddlers, through their parents, petitioned the Supreme Court of India to ban firecrackers and enforce a string of other measures to help them breathe easier. The very next year, 2016, was devastating for Delhi’s health—air quality plummeted to an all-time low, with one straight week of ‘severe’ AQI above 400, and 30 straight days of ‘very poor’ air above 300 AQ.

The subsequent years saw authorities like the Supreme Court, the Delhi state government and the Union government attempting to tackle Delhi’s deteriorating air quality problem with several new policies. Aside from banning firecrackers in 2018, the Supreme Court also ordered that vehicles in Delhi shift from BS-IV to BS-VI fuel standards, improving fuel efficiency.

Delhi’s Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, in 2016, taking into account the pollution crisis, enacted the country’s first odd-even car scheme. However, this policy was later only used during some phases and was stopped entirely by the BJP government, which came to power in 2025.

In 2017, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change introduced the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) as an emergency response to Delhi’s air quality, set to come into effect depending on the prevailing AQI. The measures under the phased approach include construction bans, vehicle entry bans, and even policies like work/study-from-home for students and civilians.

In 2019, the central government announced the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), which was supposed to be a long-term strategy to reduce air pollution in 131 cities, including Delhi, by 40 per cent by 2025-26. As of yet, there has been no update from the MOEFCC on which cities have achieved this goal.

The Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM) was formed in 2021 to coordinate air pollution action plans with the Central Pollution Control Board, State Pollution Control Boards, and ministries in the Delhi-NCR region.

“The policies are strong on paper, but there is a gap between theory and what is being practised. How strongly are construction bans being enforced? What is the actual impact of GRAP?” asked George. “These things need to be studied, and we need to learn from our mistakes.”

Decadal pollution profile change

Most policies, such as the odd-even scheme and even GRAP measures to some extent, have been criticised in research studies and by experts for failing to tackle the main sources of air pollution in Delhi decisively. According to Vimlendu Jha, environmentalist and founder of NGO Sweccha India, the crux of Delhi’s pollution problem lies in what we choose to address.

“Shifting from BS-IV to BS-VI standards, expanding metro construction, and building the Eastern and Western Peripheral Expressways were the only few good steps we made to reduce vehicular pollution,” said Jha. “Otherwise, we’ve had no big-ticket measures. If you don’t take the right measures, how can you expect to see an impact in 10 or even 20 years?”

According to Bhushan, the issue also lies in treating pollution as a Delhi-specific problem. The geographical conditions of the region demand a broader view.

“You cannot solve Delhi’s air quality by only targeting Delhi’s air quality. Delhi only makes up 3 per cent of NCR. Pollution is a problem that extends across the National Capital Region, and especially the Indo-Gangetic plains,” said Bhushan. “So all your measures need to be taken across this region, or there is no hope of solving air pollution.”

Over the last two decades, Delhi has had five different source apportionment studies to identify the main contributors to the city’s air pollution. ThePrint reported in December last year that the CAQM is currently working on a sixth one.

However, based on the data collected and the analysis methods, each study spotlights a different source—from farm fires to biomass burning to vehicular emissions to construction dust—as the largest contributor.

ThePrint’s analysis of Delhi’s decadal pollution profile makes one thing amply clear, which is that even as farm fires and stubble burning have reduced, other internal sources have risen to take their place. Increase in private vehicle ownership, as well as petrol usage, could lead to the transport sector playing a much larger role in Delhi’s air quality.