Bengaluru: Extreme weather — such as unusually high temperatures and heavy or abnormally low rainfall — during the growing season is leading to considerable crop yield losses in maize, wheat, rice and soybean across the world, Australian researchers have found.

In a first-of-its-kind study, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters (ERL) this month, scientists have concluded that fluctuations in climate indicators during growing seasons explain nearly half of global yield losses for maize and spring wheat, about one-quarter of losses for rice and one-fifth for soybeans.

The results suggest that maize and spring wheat are especially vulnerable to climatic conditions.

Importantly, more than half of this correlation was found to be only due to extreme (exceptionally high or low) temperature and precipitation conditions; near-average conditions were found to have very little impact. Between temperature and precipitation, temperature extremes were found to be more relevant in explaining crop yield losses than precipitation.

The findings suggest that extreme weather could affect food supplies across the globe as maize, corn, wheat, rice and soybeans are some of the most widely produced crops. A vast majority of the global population relies on these crops for their regular diet. The crops, in turn, rely heavily on stable temperatures and rainfall distribution during growing for maximum output.

But recent studies have shown that the current climate crisis is causing an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like heatwaves, droughts, and heavy rainfall leading to flash-floods. Such events take a heavy toll on agricultural crops and consequently on the livelihoods of farmers, and food security for populations.

The study

The study has relied on crop yield data from over 13,000 locations worldwide between the years 1961 and 2008. It also obtained temperature and precipitation data from various regional and global organisations over the same time period. The study examines plausible correlations between the two datasets.

“We used a global agricultural database that provides (year-to-year) yield data at high spatial resolution, for example, for different states or regions within a country,” wrote Elisabeth Vogel, a researcher from the Australian-German Climate & Energy College in University of Melbourne and lead author of this study, in an email to The Print.

“(Unlike previous studies) we had more local information that allowed us to gain a clearer picture of climate impacts on crop yields,” she added. These are officially reported numbers from public sources, statistical bureaus and agricultural agencies and contain a chronological record of production, yields and area harvested for each crop type and set-up (irrigated, unirrigated, local, industrial etc).

The authors used a well-established machine learning approach to disentangle the relationships between climate factors and crop output.

“The effects of climate extremes on agricultural yields are challenging to analyse because their effects can be highly complex,” Vogel said. “The algorithm we used can identify patterns in the data and this way, helps us to better understand the links between climate extremes and crop yields.”

Also read: Climate change helped wipe out these four mighty ancient civilisations

Strong correlation for crops in North America, Asia

The correlation between extreme conditions and agricultural output was particularly strong for maize production in North America and Asia, rice production in Asia, and soy production in North and South America, the study found.

North America and Asia were responsible for more than 70 per cent of global maize production (based on yield data from 1990-2008). More than 90 per cent of the global rice supply comes from Asia and more than 80 per cent of global soy supply comes from North and South America. Even small losses in agricultural yields in these regions could have major repercussions for global food supply.

While developed countries like the US in North America are relatively better equipped to deal with extreme events owing to advanced machinery and irrigation facilities, developing countries like India, where the majority of the agriculture is still rain-fed, are at the mercy of natural cycles.

Reported in the 2018 Indian economic survey, Indian Meteorological Department data indicates that the average annual temperature over India has been steadily rising since 1970, as a direct consequence of climate change. This is accompanied by a steady decline in average annual rainfall.

As the planet is heating up, the entire temperature and rainfall distributions are shifting. What used to be extreme conditions just a few decades ago, are now becoming more common. And the very-low probability events that almost never occurred before are now showing up in the distribution.

Also read: Indonesia is looking for a new capital, and climate change is to blame

The Indian factor

There are many common conclusions between the Indian economic survey report and the Australian study. Two of the most important ones are that extreme weather events are responsible for the loss in crop yields while minor fluctuations around average conditions have little to no effect.

The other conclusion is that unirrigated or rain-fed areas are significantly more vulnerable than irrigated areas.

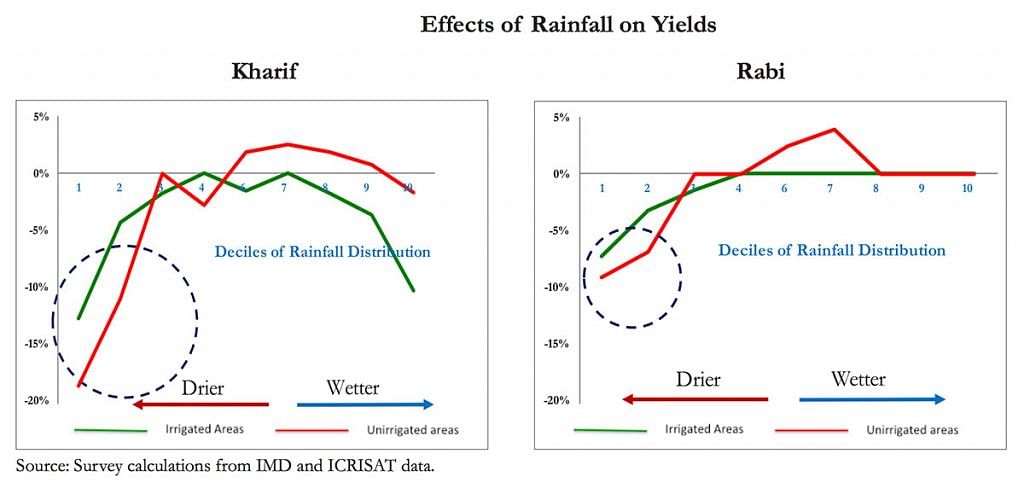

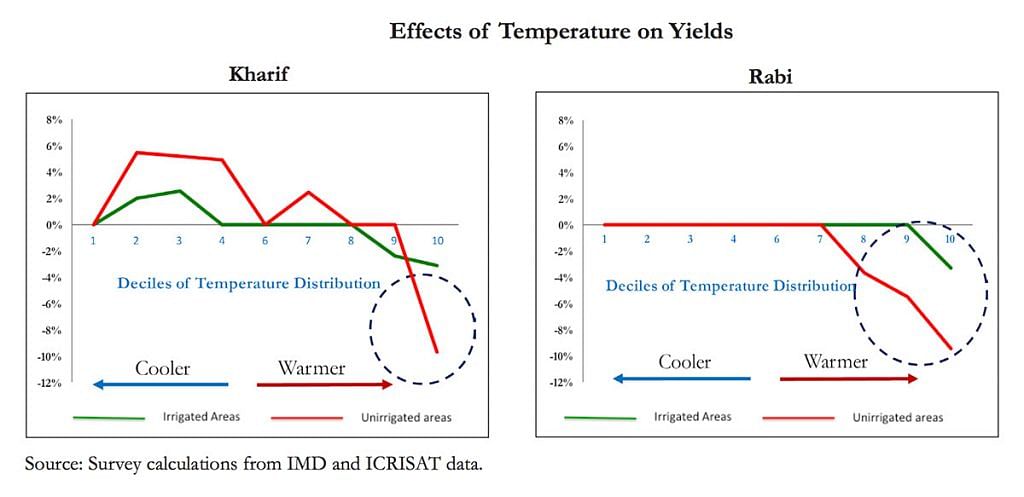

These two graphs, from the 2018 economic survey, clearly show that when temperature and rainfall are in the extreme ends of the distribution, they are associated with considerable loss in agricultural yields. The graphs also show the diverging effects of irrigated (green lines) and unirrigated (red lines) areas.

According to the survey report, “close to 52 per cent (73.2 million hectares area of 141.4 million hectares net sown area) of (agriculture in India) is still un-irrigated and rain-fed”. It also projects that “climate change could reduce annual agricultural incomes in the range of 15 per cent to 18 per cent on average, and up to 20 per cent to 25 per cent for unirrigated areas”.

In the long term, extreme weather events and limited irrigation facilities, combined with land degradation and water scarcity, will present huge challenges to Indian agriculture.

This study adds to the mounting scientific evidence suggesting that global food supply is under serious threat from climate change. Particularly from increasingly frequent extreme heat and rainfall events.

“Our results highlight the importance of climate extremes for understanding and predicting year-to-year fluctuations in crop yields,” Vogel said. “Adapting to these changes will be crucial to ensure sustainable crop production in the future and to protect the livelihoods of farmers and communities who depend on agriculture for their living.”

The author is a freelancer and has a keen interest in climate change and science.

Also read: Our best-case climate scenario could save tons of island residents. It could also be a myth