Bengaluru/Silchar/Guwahati: Joydeep Biswas, a resident of Silchar town in southern Assam’s Cachar district, is no stranger to the fury of rivers. But today even he is shocked by the floodwaters ravaging large swathes of Assam and other northeastern states.

“I was a student here (Cachar) when the floods hit in 1986 and then in the 1990s. The last big flood was in 2004. But I’ve never seen floods like these before,” recalled Biswas, a 52-year-old professor who grew up in the flood-prone Brahmaputra Valley before moving to Cachar.

It’s a common refrain here. On the intervening night of 19-20 June, the Barak river’s waters gushed through an embankment that had breached about 3km from Silchar. The town was inundated overnight. Biswas’s apartment complex was deluged too, and he and his family somehow sought shelter at a hotel. Many parts of Silchar are still under water.

It’s not just Silchar. Unprecedented floods since early April have hit most districts in Assam, affecting more than 31 lakh people so far. Twelve new deaths were recorded between Wednesday and Thursday, raising the number of fatalities due to floods and landslides this year to 151.

In neighbouring Arunachal Pradesh, at least three people died due to floods following heavy rainfall last week. In Meghalaya, over 6.3 lakh people were affected, with 36 fatalities, according to the State Disaster Management Authority.

Late Wednesday night, at least 20 people died in Manipur’s Noney district after a massive landslide was triggered by continuous rainfall. It’s a similar story in Bangladesh, where millions of people have been displaced due to floods.

“What we’re seeing right now is a once-every-100-years’ level of flooding. It should not have happened now, but it’s happening because climate change has perturbed the monsoon and is increasing the magnitude of these events,” Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) in Bangladesh, said.

This, though, is just one ingredient in a region beset with natural and human-made vulnerabilities that have caused it to grapple with ever-worsening floods over the years.

Also Read: Floating shops, rivers for roads — how floods brought economically strategic Silchar to its knees

Mighty rivers, heavy rainfall

Large, powerful river systems and heavy rainfall characterise the part of the Indian subcontinent that spans from Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Myanmar, to the eight northeastern states of India.

Fertile soil and lush greenery are the upsides, but the rough and jagged terrain and glaciers of the Indian states, and the silty, easily washed-away soil in the alluvial plains of Bangladesh increases susceptibility to flooding.

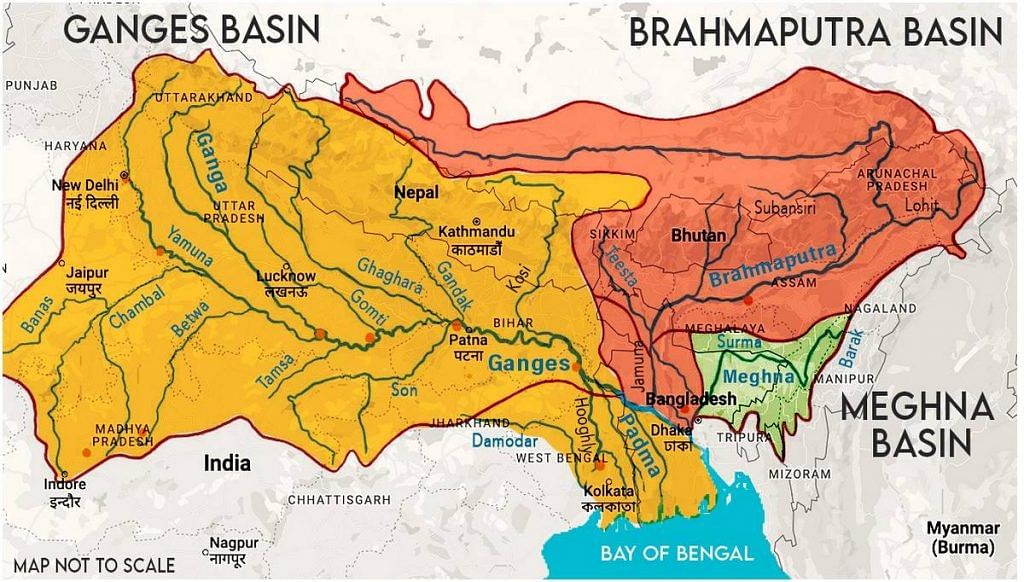

The region is part of the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) basin, one of the largest river systems in the world. It covers about 1.7 million square kilometres and more than 600 million people distributed across India, Nepal, China, Bangladesh, and Bhutan.

The three individual rivers and their intricate patchwork of tributaries, all have their origins in Himalayan glaciers.

While the Ganga originates on the Indian side, the Brahmaputra flows as Yarlung Zangpo (Tsangpo) in China’s Tibet Autonomous Region first, subsequently passing through India, and then flowing as Jamuna in Bangladesh (not to be confused with Ganga’s Yamuna). It ultimately merges with the Ganga and flows as the Padma.

The Meghna in Bangladesh, which merges into the Padma, originates as the Barak river that flows through Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, and Mizoram.

Starting from the onset of summer, around March, glaciers start to melt, increasing the volume of water flowing down the rivers. The entire Brahmaputra region receives between 1,000 and 6,000mm of rain during the monsoon, swelling from June to October.

Climate scientists Dr Ramesh Vellore and Bhupendra Singh at the Center for Climate Change Research (CCCR) at Pune’s Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) said that the intense pre-monsoon rainfall between March and May, and the post-monsoon September rainfall, are a prime driver of flooding.

”When the mainland experiences break conditions in the Indian summer monsoon (June-September), the central-eastern Himalayan foothill region stands top in receiving extreme rainfall and heavy flooding in the Himalayan rivers,” they explained in a joint e-mail to ThePrint.

The effect of heavy monsoons and an enhanced volume of water due to glacial melt causes the rivers to pick up intensity downstream, often resulting in floods.

‘Braided’ rivers and erosion

The Brahmaputra is fed by a network of tributaries carrying large amounts of silt.

“When there’s a lot of debris in the river, it makes it more shallow and reduces its carrying capacity,” said Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People (SANDRP).

The unstable flow of the large volume of boundless, shallow water in the main river, leads to the formation of several interlinked channels, which leave temporary deposit islands through their path, making it a ‘braided’ river.

The tributaries are fed by rains, causing the channels to merge during floods, forming a single wide uncontrollable mass of twisting and tumbling water.

The erosion of river banks is naturally extreme and dynamic in this river system, compounds the floods, and is also a consequence of them, worsening the intensity of the deluge each year.

Studies have shown that the Brahmaputra and the more unstable Padma erode more material than they deposit, widening steadily and loosening the soil for hundreds of square kilometres.

Survey data shows that the Brahmaputra’s span has gradually increased from 3,870 sq km in the 1920s to 6,080 sq km in 2006. The large amounts of silt it carries — at 11 million metric tonnes as of 2019 — makes it even more destructive during floods.

“A massive earthquake in 1950 also changed the Brahmaputra’s constitution, adding a lot of silt and making it shallower,” Thakkar said.

Embankments: Helpful or harmful?

While the river basin has always been flood-prone, mechanisms to cope with the flooding have led to some unintended consequences.

According to water researcher Sayanangshu Modak, writing for the Observer Research Foundation, dams, canals, and embankments were introduced as flood-control measures by the British, and have become “the dominant institutional response” to prevent floods.

However, the “haphazard and unscientific construction” of some embankments has meant that silt that would normally get distributed in the adjacent plains during floods now gathers in the river channel, leading to the riverbed getting raised, Modak said.

Many embankments fail to contain the Brahmaputra, with the force of the waters destroying protection put in place by humans in the region — typically makeshift flood walls and, in some cases, geotubes. Occasionally, these are even said to prevent the water from receding back, causing land to remain waterlogged.

Out of 423 embankments along the Brahmaputra in Assam, 295 — dating back to the 1940s — are vulnerable to breaches, according to local reports. A paper in the journal Nature found said islands in southwest Bangladesh lost 1-1.5 metres of elevation due to embankments built in the 1960s.

Meanwhile, government agencies have emphasised upgrading existing embankments and building new ones.

In an August 2021 report, the Standing Committee on Water Resources underlined that most of the embankments on the main stem of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries were built in the 1960s and 1970s, and required raising and strengthening, “as well as bank protection measures in form of revetment or reinforced cement concrete (RCC) porcupines…”

In January this year, the Assam government announced that it would build 1,000 km of concrete embankments at an estimated cost of Rs 1,500 crore.

According to Thakkar, though, embankments are short-term solutions that are most efficient at the time they are built, losing their ability to perform with the passage of time.

“Embankments along the river have made the problem worse, because silt gets deposited within them, making it even more shallow,” he said. “When the river breaches one of the embankments, it’s catastrophic because of how the water rushes out.”

The impacts of the floods have been made worse by deforestation and the removal of mangroves, Huq of ICCAD-Bangladesh said.

Mangroves are known to protect low-lying coastal areas from storm surges by breaking up waves. They also keep the land stable by retaining sediments and reducing erosion.

“We have to be careful to let water flow into the wetlands. Instead, we have built roads in those areas, which is bound to make the impacts of flooding much worse,” Huq added. “Building roads and embankments along and over rivers is a form of maladaptation.”

Construction of roads involves removal of vegetation, depressing the surface, and reducing infiltration of water to maintain structural integrity. Roads are always at risk of collapsing in floods.

Roads may also cause rainwater and floodwater to drain inefficiently, and are often built transverse to natural drainage channels, blocking smaller water pathways. They also lead to accumulation of deposited silt carried by river, causing localised blockages to water drainage.

The case of Assam

Extreme flooding in Cachar, which is located in the Barak Valley, Assam, has followed the familiar pattern of flooding from heavy rainfall resulting in embankment breach, followed by towns and villages getting inundated.

Speaking to ThePrint, Cachar deputy commissioner Keerthi Jalli said the first wave of floods hit the area on 14 May.

“The Barak river crossed the danger level at the time. Cachar was also affected by severe rainfall. Waters from the North Cachar hills, Meghalaya, and Manipur flow into the catchment area of Cachar district, which then moves on to Bangladesh and then to the Bay of Bengal,” she said. “It finally went below the danger level on 23 May.”

However, on 18 June “it crossed the danger level again, rising up by 1 m within 24 hours”.

Finally, the waters gushed through the breach in the embankment engulfing the nearby town of Silchar.

The Brahmaputra flows through the length of Assam, along with the Barak, making the entire state flood-prone.

Jayanta Kumar Sarma, an Assam-based independent consultant who works in the domains of development and the environment, said that over the past three decades or so, “pressure” had increased in the river basin areas due to human activities, including settlements and “structures on rivers and river corridors” like bridges, dams, and embankments.

“The concomitant effect of these can be seen,” he said, in the increased intensity of the flooding.

Global heating worsening everything

Experts say increasing air and surface temperatures have a role to play in the unprecedented floods that have been upending lives and economic activity in the region.

“Increase in atmospheric temperature causes more water to evaporate, adding moisture to the air. This fuels extreme precipitation,” climate scientists Vellore and Singh said. They pointed out that the Ministry of Earth Sciences has started using the term “mini-cloudbursts” in its reports for intense, short-duration rain, which shows a rising trend along the Himalayan (and Western Ghats) foothills.

Excessive melting of the Himalayan glaciers has added to the deluge of water that enters into the Brahmaputra from the north bank, bringing with it even more silt.

At the other end, the flatter terrain of Bangladesh is also particularly prone to cyclones from the Bay of Bengal, strengthened by climate change and increasing flooding events.

In addition, studies have shown that the monsoon pattern in India has been steadily affected by rising global temperatures, and the increasingly frequent marine heatwaves could cause magnified changes to the seasonal rains on which at least one billion people rely.

According to the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, Assam is among the most vulnerable states in India, prone to extreme climate events.

Every one degree rise in temperature brings with it a 7 per cent increase in moisture, disproportionately affecting the South Asian monsoon, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Global temperatures have already risen by 1.1 degrees since pre-industrial times.

IITM’s Vellore and Singh, who also model climate scenarios, said that future projections of the different climate pathways show “robust” changes in many key parameters such as land temperature, precipitation, tropical cyclones, Himalayan cryosphere (frozen parts), and so on, which spells bad news for the region.

“With such a topographically complex region, an increase in rainfall extremes in a warming environment, accompanied with increased glacier melting, may likely contribute to frequent and more intense extremes in the future,” they added.

‘Measures have been temporary so far’

Until now, relief and rescue measures have largely been short-term and reactive, according to researcher Jayanta Sarma.

“Whatever relief and rescue measures there are, are very temporary… even embankments are temporary,” he said, echoing other experts.

Instead, there is a need for “structural” and “long-term initiatives”, he added. These include a focus on livelihood support for people living in affected areas as well as “river basin management, catchment area treatment, watershed management, riparian management to maintain the river corridors, its flow networks, and land and soil conservation and protection”.

Further, given the rapid rate of urbanisation, city/town planning has to take into account rain predictions for 30 years, he said, adding that various climate change studies “indicate there will be more rainfall in the urban meteorological zones of the northeast, like in Hojai, Karbi Anglong, Dima Hasao, and Silchar”.

Experts also believe that more emphasis should be placed on “traditional knowledge-based practices” for land and water management. “With the disappearance of such practices, the precarity has also intensified in certain areas,” Sarma said.

Mirza Zulfiqur Rahman, an Assam-based independent researcher, stressed that local communities should be involved in implementing flood preparedness measures.

“Communities have been living with floods for decades,” he said. “Listening to their voices and then trying to make implementations before the floods can help minimise the impact.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Monsoon has turned normal, IMD says. But it really hasn’t if you see regional variations