Gurinder Chadha’s film on partition has no real victors – all characters are taken over by a sense of defeat and betrayal. And it’s just as well.

It is after 37 long years that a film on the Indian partition has been released in Britain, and the difference between the two films is stark.

While Gandhi was directed by British director Richard Attenborough, British Indian director Gurinder Chadha’s Partition: 1947 is a clear attempt to challenge the British narrative of the world’s largest forced migration.

Chadha begins her touching rendition of the tumultuous year, which was screened in the capital on Friday, with the quote “history is written by the victors”. The rest of the screen time is spent on offering a version of history which has no real victors.

A helpless viceroy and his wife, a regretful Nehru, a delusional Jinnah, a heartbroken Gandhi and an agonised population – the film shows each character at the time feel defeated and betrayed by circumstance in their own way.

The conflicts and tentativeness within each side are brought to the fore such that even the villains – the British – are lent a kind of humanness.

Nobody knows what’s really going on. Those passing decrees on behalf of millions are as shocked by the ramifications of their decisions, as the rest of the population. Jawaharlal

Nehru, who after his determined position against the partition, finally gives in to the demand, is full of tears and remorse to see the misery it brought.

Jinnah, whose demand for a separate country is met, remains delusional of the future of his country. It’s his unflinching belief until the end that the minorities in his Pakistan would enjoy the freedom and equality that those in India would never be able to.

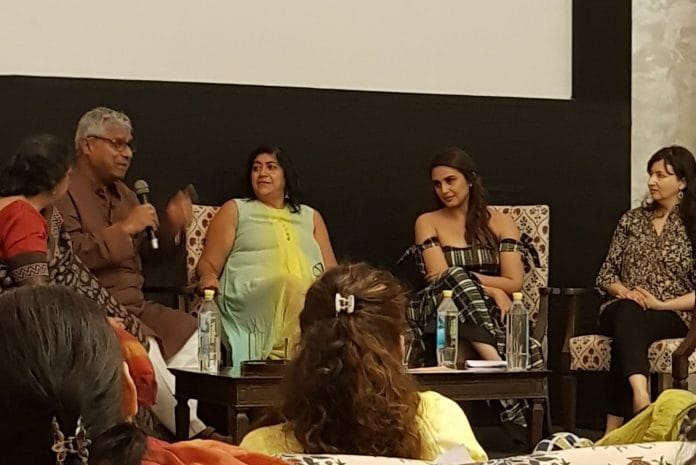

But as Aditya Mukherjee, a professor of history at Jawaharlal Nehru University, remarked in the panel discussion following the screening, Jinnah ought to have known that one cannot ride a tiger and then hope to get off.

Gandhi, whose character in the film is peripheral, has a lingering presence throughout. His forewarnings of the tumult, misery and chaos that the partition would bring, are felt even as his character remains on the margins. On the day of independence, when there is celebration all around masking the hate and hardship of the time, Gandhi is asleep. For him, the ephemeral festivities of the heartbreaking independence meant nothing.

Away from the high table tension and chaos, there is also a love story in the film, whose fate hinges entirely on the diktats of the rulers. Played by Huma Qureshi and Manish Dayal, the young inter-religious couple’s love, heartbreak, separation and ultimate reunion give the horrors of partition a healing touch.

Their relationship is like a microcosm of the world they inhabited at the time. As Qureshi said, the film and their love story, in particular, reintroduces partition to the world 70 years on without the anger, accusation and the “us versus them” narrative that it usually entails. “It is time we moved on from the hate,” the 31-year-old actor said.

The film is also historically crucial, for it challenges the dominant narrative on how the “Radcliffe line” of separation between India and Pakistan was actually drawn.

As opposed to popular belief, Cyril Radcliffe was not actually the architect of the boundary demarcation line, Chadha’s film contends. In fact, a map dividing India and Pakistan exactly the way the “Radcliffe line” does existed long before Radcliffe even set foot on Indian soil.

A clandestine agreement between Winston Churchill and Mohammad Ali Jinnah over India’s partition was already made in 1946, and Mountbatten and Radcliffe were sent to India only to execute the plan, which they actually had no say or control in conceptualising. “Partition only happened because it was in the British interest,” Chadha said.

Seventy years on, there are a lot of lessons from partition that remain to be learned, the panelists said. People are being killed for the flesh of an animal, said Qureshi, adding that she was recently trolled on Twitter for her surname. “We’re doing the exact same things today,” Mukherjee rued. “We’re creating refugees within the country even today.”

There is no way Partition could not have happened. West and East Pakistan, unified by religion and a shared outlook towards India, found they could not coexist. What hope that the rest of us could have shared a kitchen with people with whom we are still not on talking terms … 2. The real tragedy is that the British, with two hundred years of ruling the subcontinent, made such a hash of executing the deed. With a few more months to plan and assemble forces to provide security, ensuring that the exchange of populations was orderly and peaceful, the departing rulers could have prevented the loss of two million lives and a residue of bitterness that the two nations have still not been able to overcome. 3. Should there be a memorial to Partition ? I think we need to forget, not to remember.