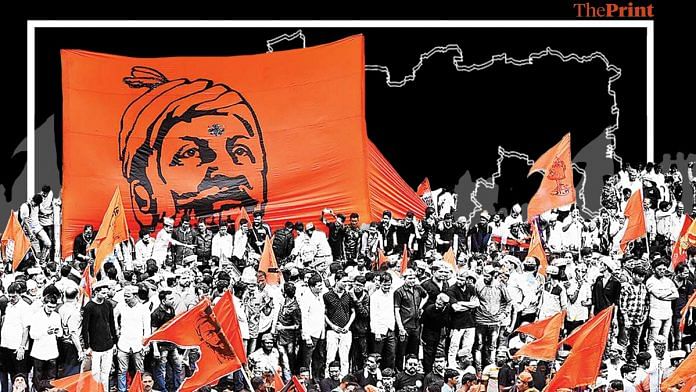

Mumbai: Maharashtra has once again been gripped by protests by members of the Maratha community agitating for reservation in government jobs and education.

The state government has formed an advisory board of retired judges to oversee the government’s preparedness in presenting its case in the Supreme Court to push for the quota.

CM Shinde on Monday said the government would accord reservation to the Maratha community under two schemes – one, via Kunbi caste certificates and the second on the basis of economic backwardness that will undergo legal scrutiny.

The CM said a committee appointed to study the possibility of reservations to Maratha Kunbis had already submitted a preliminary report, and will file its final report in December this year.

He cited a first report submitted by the Justice (Retired) Sandeep Shinde committee — formed to study the procedure of giving Kunbi (OBC) certificate to Marathas — to reveal that 1.72 crore documents had been collected so far, and 11,530 had evidence to support Kunbi eligibility.

The Supreme Court had in 2021 struck down Maratha reservation in Maharashtra that took the total quantum of reservation in the state to above 50 percent.

In April this year, the court rejected the state government’s review petition on the issue, after which the government said it will file a curative petition.

Meanwhile, Manoj Jarange Patil, a Maratha community leader, is on an indefinite fast demanding that the government give ‘Kunbi’ caste certificates to all Marathas in Maharashtra so that they are eligible for reservation under the ‘Other Backward Classes’ category.

The Maratha community — from powerful sugar barons and landlords to distressed farmers and unemployed youth — comprises 32 percent of Maharashtra’s population and has been demanding reservations for more than two decades.

Between August 2016 and August 2017, it organised 58 silent marches. In 2018, the protests had even got violent.

Also read: No let-up in Maratha anger & violence despite weekend overtures by Maharashtra CM Fadnavis

Who are the Marathas?

The Maratha community, which primarily lives in the state’s Marathwada and western Maharashtra regions, is highly stratified. The community comprises peasants, cultivators, aristocrats and rulers and there exists a clear hierarchy. The 1980 Mandal Commission classified Maratha as a forward caste.

Loosely, there are four main classes among the Marathas.

The elite who are either power centres themselves or in close proximity of power centres —Maratha politicians, ministers, directors on boards of district cooperative banks or sugar factories and so on. Below them are the wealthy farmers with large landholdings cultivating cash crops. These Maratha farmers wield significant influence and authority in their villages. Below them is the class of small to mid-sized farmers who depend on the season’s crop for their subsistence and are deeply impacted by the vagaries of nature. Then there are the very poor farmers and landless labourers.

Maratha leaders argue that the condition of the bottom two classes, which comprise most of the Maratha population, has worsened with bouts of drought and agrarian crises.

A study by the Pune-based Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics said 26 per cent of the 3,880 farmers from the Marathwada and Vidarbha regions who committed suicide between April 2014 and March 2016 were from the Maratha community. In Marathwada particularly, 53 per cent of the farmers who killed themselves in despair belonged to the Maratha community.

Pravin Gaikwad, a leader of Maratha organisation Sambhaji Brigade and an expert in reservation studies, had told ThePrint in 2018 that all classes of Marathas are ultimately tied to farm land and the stratification developed more out of a revenue or tax structure.

The perception is that the Maratha community takes pride in identifying itself as Kshatriya, but Gaikwad said the community has always belonged to the Shudra fold and there is enough documentary evidence to support it.

“The janma-patrikas of members from the Maratha community state their varna (caste) as Shudra. Even today, there are temples where people from the Maratha community are not allowed to enter,” he said.

He added, “Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj took weapons in his hands, established and grew the Maratha empire. But as per dharmashastra, the Marathas remain Shudra. Just because someone wants to call a Shudra a Kshatriya, the issues of the community do not change.”

Marathas and Kunbis

Some leaders, including Gaikwad, argue that being farmers, Marathas are Kunbis too and demand a quota for Marathas under Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The Kunbi caste gets reservations under the OBC category.

A paper titled Political Economy of a Dominant Caste, authored by Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar explained the distinction between Marathas and Kunbis. It said, the Maratha claimed a Kshatriya rank and showed pride in their Rajput lineage, while Kunbis were cultivators and were considered Shudras.

“Sections of Kunbis, especially from western Maharashtra and Marathwada region of the state, tried to merge with the Marathas, often through marriage links. They could do so both due to the landowning pattern in these regions and a historically developed close interaction among these groups. In the regions of Vidarbha and Konkan, Kunbis retained their distinct caste identity. At present, they account for around 10 percent of the state’s population and are concentrated in the above two regions,” the authors said in the paper.

The paper said the proper Marathas always opposed moves of Kunbis towards “upward mobility,” and that it was the Congress that largely projected the Maratha-Kunbis as a homogenous group and as the dominant cultural and political force within the Marathi community.

Besides the Mandal Commission report, the National Commission for Backward Classes report of 2000 rejected the demand for the Maratha community to be included under OBCs. In 2008, the Maharashtra State Backward Class Commission called the Marathas an economically and politically forward class.

Under pressure to act on the Maratha community’s demand for reservations, the Prithviraj Chavan-led Congress-Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) government appointed a committee under Narayan Rane, who was then a Congress leader, to study the issue. The committee recommended reservation for the Marathas without infringing on the existing OBC quota. In July 2014, the then Chavan-led government passed an ordinance to have a 16 percent Maratha quota in government jobs and education, but the decision could not withstand the Bombay High Court’s scrutiny.

The Devendra Fadnavis-led government undertook a survey to prove the social and economic backwardness of the Maratha community, based on which it passed a Maratha quota law for 16 percent reservation to the community in November 2018.

The Bombay High Court upheld the decision but tempered down the quota to 12 percent in education and 13 percent in jobs. The Supreme Court scrapped the quota calling it “unconstitutional” in 2021.

Also read: Maratha protest shows Maharashtra is no better than casteist Bihar or Uttar Pradesh

Maratha community’s political dominance

Since the state’s formation in 1960, 11 of Maharashtra’s 20 CMs have been Marathas. The state’s first CM, Yashwantrao Chavan, was also a Maratha. As is the incumbent CM, Shinde.

Marathas have always comprised about 30 to 40 per cent of the state’s elected representatives and the community has had a significant share of ministers in consecutive state cabinets.

Shantaram Kunjir, a Maratha leader from Pune, had told ThePrint in 2018 that a number of people had made an argument against Maratha reservations citing the community’s political significance. “But the truth is that members of the Maratha community who rose to political significance have failed us. They have done nothing to uplift the larger Maratha population. That is the main reason why the previous government was toppled in 2014,” said Kunjir, who died in 2020 following a heart attack.

The Congress and Sharad Pawar-led NCP, traditionally seen as parties of the Marathas, have dominated the political landscape in western Maharashtra and Marathwada. The BJP made significant inroads in these regions in the 2014 polls.

Kunjir added, “Members of the Maratha community are as angry at Congress and NCP as they are against the current Devendra Fadnavis-led government. All Maratha CMs too made promises to implement the Maratha quota, but none of these promises materialised.”

An Economic & Political Weekly report, analysing the composition of Maharashtra cabinets from 1960 to 2010, suggested that though Maratha ministers dominated cabinets, the phenomenon had a distinct regional profile with power focused in the hands of Marathas particularly from western Maharashtra.

The report, titled Maharashtra Cabinets Social and Regional Profile, 1960-2010, authored by Abhay Datar and Vivek Ghotale, said 78 of the 173 cabinet ministers from 1960 to 2010 were Marathas/Kunbis and of the 16 cabinets till 2010, Marathas dominated 10. Incidentally, one of the six when the Marathas were not in majority was the Manohar Joshi-led cabinet of the Shiv Sena-Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government from 1995 to 1999.

Ironically, some of the same Maratha leaders who are now at the forefront demanding reservations were vociferously against the quota policy in the 1980s. The Maratha Mahasangh was one such organisation.

Kunjir said, “It is true that some organisations and leaders, especially from western Maharashtra were against reservations. Western Maharashtra has always been slightly better off than Marathwada.”

He added, over the years, farming has become unviable with the average size of landholdings reduced and even western Maharashtra hit by water shortage and lack of sufficient irrigation. “Entire talukas and villages are dry. The situation has considerably changed over the years,” Kunjir said.

Also read: CM Fadnavis offers special assembly session on quotas to make peace with angry Marathas

Two issues are getting mixed up in the reservation debate : economic deprivation and social discrimination. Dalits, who have created their own elite over three generations benefiting from affirmative action, claim, somewhat disingenuously, that even those members of the community who have prospered still feel the sharp edge of social prejudice. So their claim to reservation is not just that they are poor but that society owes them reparations for centuries of prejudice. 2. As far as dominant, land owning communities like the Marathas are concerned, they face no social discrimination and prejudice. Whether they are Kshtriyas or Shudras is a semantic debate. They are demonstrating for reservations because many of them are not doing well economically. Once this principle is accepted as the basis for reservations, members of all communities, in greater or lesser number, would qualify. Even Muslims, most certainly, although the standard put down for them is that the Constitutional does not allow for reservation on the basis of religion. 3. It is clearly a fudge to give reservations to Marathas by classifying them as “ backward “. That, by no stretch of the imagination, they are. If people should qualify because they are not economically well off, then, as Shri Nitin Gadkari has said, reservations should be given, neat and clean, to members of all communities, across the board, who are at the bottom of the heap. 4. The apex court has, very wisely, placed a cap of 50% on reservations, balancing efficiency and equity. Tamil Nadu has found a way out. Now Maharashtra will. Given electoral compulsions, the political class would not mind taking reservations to 100%. What happens to the interests of groups who cannot be covered by reservations, and what happens to the sense of fair play that underpins the social compact ? 4. No better way to end this rant than by quoting Gadkariji again : But where are the jobs ? How much would the Marathas gain if they get 12,000 of the 72,000 jobs on offer ? All these agitations are actually a cry from the heart of real India – the economy is not creating the growth and the jobs it should. That is what China has achieved and we have not.

This demand for reservations from Marathas, Jats, Patels etc are a disgusting trend! These communities are all dominant castes with wealth and power and definitely not backward or exploited! These should be resisted strongly and put down remorselessly. What next? Demands from Reddys and Naidus, Mudaliars and Nairs etc. No end to this self-centred, violent and immoral agitations?