PastForward is a deep research offering from ThePrint on issues from India’s modern history that continue to guide the present and determine the future. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Indians are now hungrier and curiouser to know what brought us to key issues of the day. Here is the link to the previous editions of PastForward on Indian history, Green Revolution, 1962 India-China war, J&K accession, caste census and Pokhran nuclear tests.

In a judgment that will have far reaching consequences, the US Supreme Court last week overturned its own 1973 Roe vs Wade judgment against state restriction on abortion, setting women’s sexual and reproductive health rights back by many decades.

Roe vs Wade was a landmark when it was originally passed; but what is less known is that Indian women’s right to abortion predated that seminal case when Norma McCorvey, a Texas resident, challenged Henry Wade district attorney of Dallas county, demanding the right to abort her baby. Although, by the time the right to abort came, McCorvey had already delivered her baby. Jane Roe was the alias used to protect her identity.

Two years before the US Supreme Court judgment, in India, women’s right to seek an abortion was established by the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971. Much water has flown under the bridge since then. In 2021, the revised MTP Act took into account changed social realities and also the advancements made in medical field, which expanded the safe abortion window considerably. The most important change that the 2021 law brought was not the expansion of permissible limit for abortion from 20 weeks of gestation to 24 weeks. It was in its recognition of the need to make abortions accessible for all women irrespective of their marital status.

ThePrint takes a look at how India’s abortion law evolved.

Also read: Who was Jane Roe of Roe v Wade? What overturning of the 1973 judgment means for American women

MTP Act, 1971

The MTP Act of 1971 allowed abortions up to 20 weeks provided two registered medical practitioners agreed that continuing the pregnancy involved a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or the unborn child, including mental or physical abnormalities. For a pregnancy caused by rape, the law allows abortion, holding that pregnancy in such a case “presumed to constitute a grave injury to the mental health of the pregnant woman.” Contraceptive failure was also an acceptable ground for abortion in case of a married woman as per this law.

The genesis of the law lay in a government committee that was constituted in 1964, much before Roe vs Wade’s initiation date of 1970. Until then, Indian law had a provision for an imprisonment of up to three years for the provider of abortion services and of up to seven years for the woman seeking those services. Exception was allowed in the case of miscarriage to save the life of the pregnant woman “in good faith”.

In its report submitted in 1966, the committee headed by then-minister of public health, law and judiciary Shantilal Shah said: “The committee considers the above provision too restrictive; and therefore recommends that it should be liberalised to allow termination of pregnancy by a qualified medical practitioner acting in good faith…” However, the committee was clear that abortion was unviable as a method to control population growth.

A 2016 article in the journal Indian Law Institute Law Review noted that “the MTP Act was implemented in the month of April, 1972 and again revised in the year of 1975 to eliminate time consuming procedures for the approval of the place and to make services more readily available. This Act was amended in the year 2002 and again in 2005.”

Also read: How changes to pregnancy termination bill give women better options for abortion

The question of limit

Throughout the amendments in the MTP Act, there was one constant — abortions were legally allowed in the country only till 20 weeks of pregnancy. This had to do with the available medical facilities and the assessment at those points of time about what constitutes a safe window for abortion without jeopardising the life of the mother. But with the advent of advanced medical equipment, it became possible for doctors to detect foetal abnormalities well beyond the 20-week deadline, making the decision of carrying pregnancy through a fraught question for the would-be parents.

One such instance came in 2008 when Mumbai couple Haresh and Niketa Mehta approached the Bombay High Court for permission to abort their baby, which doctors said would be born with a congenital heart block. Their application was turned down and Niketa eventually miscarried. The case became one of the landmarks in the long journey of the Indian abortion law in allowing abortions beyond the 20-week barrier.

There have been cases where courts have granted permission beyond the permissible time limit. In 2015, a 14-year-old rape victim from Gujarat was permitted by the Supreme Court to abort after 20 weeks as a “special case”. The court, however, asserted that this case could not be used as a precedent to grant permission in another similar case.

On the other hand, in 2020, the Kerala High Court denied permission to a couple to abort their 35-week foetus.

The longstanding need to review the limit in gestation age, which doctors and patients have been arguing in favour of for years, was finally met in 2021 when a new MTP Act came into force that allowed abortion up to 24 weeks. The upper gestation limit, the law says, will not apply in cases of substantial foetal abnormalities diagnosed by a medical board. The board will include one paediatrician, one gynaecologist and one radiologist or sonologist. But why that law marked a shift in mindset lies in a paragraph which says: “For the purposes of clause (that is when the pregnancy is less than 20 weeks old), where any pregnancy occurs as a result of failure of any device or method used by any woman or her partner for the purpose of limiting the number of children or preventing pregnancy, the anguish caused by such pregnancy may be presumed to constitute a grave injury to the mental health of the pregnant woman.”

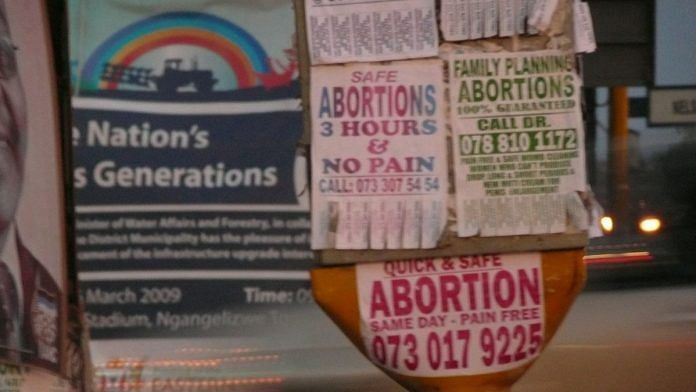

This was a major shift from the earlier law when contraceptive failure was an acceptable reason for abortion only for married women, leaving many unmarried pregnant women at the mercy of quacks and illegal service providers. The original draft of the Bill had included the contraceptive failure clause only for married women but the ministry of health pushed for a more inclusive language to ensure better access to safe abortion services. According to a 2018 study by the Guttmacher Institute, 50% of pregnancies in six of the largest Indian states — Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh — are unintended. According to United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)’s State of the World Population Report 2022, 67 per cent of all abortions that happened in India between 2007-2011 were unsafe.

Also read: Why India’s law on abortion does not use the word ‘abortion’

The question of providers

The two thorny questions in the abortion law have always been: who can deliver the essential health service and who can seek it — the latter being more of a social nature but one that requires a legal framework. India’s position on this question has evolved with time, taking into account social realities so that the question of who needs an abortion is now looked at through the prism of individual rights rather than societal norms. But in a country where doctors are chronically in short supply — even the 1966 report mentioned this problem — the question of who is qualified to provide abortion services is complicated as well. So, around 2014-15, the ministry of health and family welfare proposed an amendment to the MTP Act, 1971 to allow ayurveda, naturopathy, and homeopathy practitioners to perform medical abortions — that is, abortions that did not require any surgical intervention.

The proposal caused a backlash, particularly from the Indian Medical Association (IMA), the largest body of allopathic doctors in the country. But what put paid to the plan was not the uproar but the death of a woman in Maharashtra’s Sangli district in 2017, allegedly after she sought an abortion from an unqualified person. A homoeopathy doctor was later caught allegedly running an illegal sex-selective abortion racket. Following the incident, the MTP Act, despite being included in the agenda of the Union Cabinet, was not taken up for several months. The PMO stepped in and asked the health ministry to ensure better implementation of the MTP Act, 1971 and the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act, 1994 before trying to amend either. The PCPNDT Act is meant to stop sex selective abortions. The Sangli incident also caused concerns in the highest levels of the government about the implications of increasing the provider base in a country where regulations tend to fall repeatedly short.

The plan to allow practitioners of alternative medicine to perform abortions was dropped and eventually when the MTP Act, 2021 came into effect, the status of a provider was limited only to qualified allopathic practitioners.

The MTP Act, 2021 was hailed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a progressive step towards equitable access to abortion services. “In a historic move to provide universal access reproductive health services, India amended the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act 1971 to further empower women by providing comprehensive abortion care to all. The new Medical Termination of Pregnancy (Amendment) Act 2021 expands the access to safe and legal abortion services on therapeutic, eugenic, humanitarian and social grounds to ensure universal access to comprehensive care. The new law, which came into force from 25 March 2021, will contribute towards ending preventable maternal mortality to help meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3.1, 3.7 and 5.6,” WHO said in a statement in April 2021.

(Edited by Prashant)