New Delhi: On 23 May 2019, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Narendra Modi won the most decisive mandate by any incumbent since Indira Gandhi’s Congress government in 1971.

Just three months before, in February, in response to a terrorist attack in Pulwama, Jammu and Kashmir, the Indian Air Force crossed the Line of Control and conducted air strikes in the town of Balakot in Pakistan’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province. This strike was a central theme of the BJP’s re-election campaign.

Nearly seven decades ago, in 1947, militia from the same Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa region, then known as the North West Frontier Province, dressed in plainclothes, conducted a surprise invasion on Jammu and Kashmir. Just a few months after Independence, this invasion would kick-start the protracted India-Pakistan conflict centred on Kashmiri territory.

What connects the two events? Twenty-one years ago, in May 1998, both India and Pakistan conducted nuclear tests. Over the next 12 months, these two rivals went from making one of the most significant peace overtures to fighting the world’s first and only hot conflict between two nuclear powers.

These 12 months in 1998-99 transformed the India-Pakistan rivalry. Nuclear weapons have since ensured a certain deterrence, and demonstrated that they may not be used in the resolution of political disagreements. But even seven decades after Partition, the rivalry with Pakistan is a substantial vote-fetcher in Indian politics.

This is ThePrint’s Past Forward. Through a series of interviews, research and reporting, the aim is to recreate The Year That Changed South Asia. This is the first of a three-part story that begins with India’s nuclear tests in May 1998 and ends with the Kargil War in 1999. But its origins and impact are not limited to these 12 months.

The Pokhran explosion

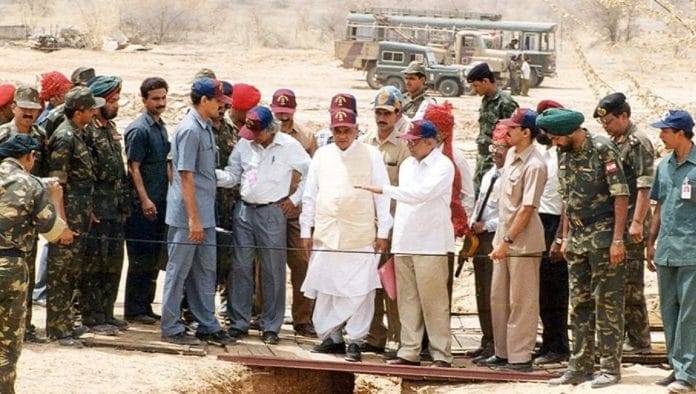

“Today, at 15:45 hours, India conducted three underground nuclear tests at the Pokhran range,” announced Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in a televised press statement.

It was 11 May 1998, and the world shook with Vajpayee’s announcement. Another test was conducted two days later, on 13 May.

A couple of weeks later, as expected, Pakistan conducted its own tit-for-tat nuclear tests at Chagai in Balochistan on 28 May.

While declassified American intelligence reports and a lot of reported accounts suggest that Pakistan had already achieved nuclear capability during the 1980s, India’s decision to test forced Pakistan to come out of the closet. Within a matter of few weeks, an already hostile South Asia had been turned into the world’s gravest nuclear hotspot.

Then US President Bill Clinton would go on to refer to South Asia as the “most dangerous place on Earth”.

Vajpayee had inherited a tense security situation with Pakistan — India and Pakistan had been locked in an escalating ballistic missiles testing spree. But Vajpayee not only claimed to be strong on national security issues, he also wore it on his sleeve.

“[We will] re-evaluate the country’s nuclear policy and exercise the option to induct nuclear weapons,” declared the BJP’s manifesto released in January the same year.

Former diplomat and the party’s spokesperson on national security, Brajesh Mishra, who would go on to become the National Security Advisor, said during the manifesto launch: “Given the security environment, we have no option but to go nuclear.”

The tests were conducted less than two months after Vajpayee’s National Democratic Alliance government came to power — it had proved its majority in the Lok Sabha on 28 March 1998.

Although Vajpayee was the first Indian prime minister since Indira Gandhi (in 1974) to authorise a test, the development of India’s nuclear capability involved decades of hard work by several unsung scientists.

1989: A failing PM makes a bold move

India’s nuclear programme was initiated right after Independence in 1947. Owing to the contributions of esteemed nuclear scientists such as Homi Bhabha and Vikram Sarabhai, the country detonated its first nuclear bomb in 1974. But it turned out to be an unsuccessful test and led to sharp sanctions on India by Western powers.

Contrary to the expectations of all global powers, India would not conduct another nuclear test for the next 24 years.

“The fact that India did not conduct another test immediately after 1974 surprised the global nuclear powers. But the Indian leadership calculated that another test would lead to more sanctions and the costs from another nuclear capability outweighed the gains,” George Perkovich of the think-tank Carnegie Endowment told ThePrint.

But by the late-1980s, India had begun to feel the pain of the armed insurgencies in Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir, sponsored and aided by Pakistan. In 1989, Rajiv Gandhi, the then-prime minister, took a call — he had made up his mind to make India a nuclear state.

Defence secretary Naresh Chandra was installed as the head of India’s secret nuclear mission, and the team included V.S. Arunachalam, the head of the Defence Research and Development Organisation, renowned nuclear scientists P.K. Iyengar, R. Chidambaram, Anil Kakodkar, missile man A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, and others.

From 1989 to 1998, India’s nuclear programme was a tightly-guarded secret. In this period of political turbulence, New Delhi saw seven different prime ministers. They all had the secret nuclear file on their table and not a word ever got leaked to the press.

Over this decade, the nuclear programme was also funded secretly. Nothing got on the government’s public accounts, and the operation was kept “out of the system”. The money came from the annual budgets under the nondescript “science and technology” allocation to the Planning Commission.

The successful nuclear test in 1998 is one of the greatest instances of bipartisanship and patriotism among India’s top political leadership.

Also read: Pokhran anniversary: How India pulled a fast one on the Americans

Why did India go nuclear?

The year 1998 was not the first occasion when Vajpayee authorised the scientists to conduct a nuclear test. Back in 1996, in his short-lived 13-day government, Vajpayee authorised a test, but was forced to withdraw his decision.

So, what had suddenly changed in the mid-1990s that forced the Indian leadership to go nuclear? After all, Indian intelligence agencies had been aware of Pakistan’s nuclear capability for some time.

Although the Chandra led-nuclear group had aggressively started working towards a bomb, until 1995, the Indian policy had been to achieve all the technical capacity and know-how, so that a nuclear weapon could be built in a matter of weeks or even days, but not necessarily to conduct a nuclear test per se.

But India’s position quickly changed when in 1995, America and other nuclear powers indefinitely extended the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

“The tests carried out on 11 and 13 May in 1998 were in reality ‘against nuclear apartheid’… The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) was extended indefinitely and unconditionally in 1995… perpetuating the existence of nuclear weapons in the hands of five countries (N-5), who went on to modernise their respective nuclear arsenals,” wrote Jaswant Singh, who became Vajpayee’s Minister of External Affairs a few months after the tests.

Moreover, during the same period, there was severe pressure on India to sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) — which would restrict India from conducting a nuclear test.

These changes at the international level had a transformative impact on Indian security thinking.

“India had to ensure that its nuclear option, developed and safeguarded over decades, was not limited by any self-imposed restraint… The nuclear tests it conducted on 11 and 13 May 1998 were not only inevitable but a continuation of policy from almost the earliest years of Independence,” Jaswant Singh wrote.

Given the fact that two nuclear-power neighbours surrounded India, conducting a nuclear test was an eventuality. But there was more to it.

For India, testing a nuclear weapon was also necessary for its pursuance of big power status. The Indian leadership, with Vajpayee at the top, felt that conducting a nuclear test was a necessity if India wanted to be taken seriously by the world.

This indeed turned out to be the case.

“The week (of 11 May 1998) was no longer normal, and India was no longer merely important,” remarked Strobe Talbott, the American Deputy Secretary of State at the time.

Dealing with nuclear sanctions and a rattled Pakistan

India’s nuclear tests had fundamentally altered its relationship with its neighborhood and the world at large. The fact that Pakistan retaliated with a tit-for-tat nuclear test meant that, suddenly, South Asia had emerged as the world’s nuclear hotspot.

“Given the nuclear tests, there was tremendous global pressure on India to negotiate with Pakistan,” G. Parthasarthy, India’s High Commissioner to Pakistan at the time, told ThePrint.

The Clinton administration in the US responded by enforcing tough economic sanctions on both India and Pakistan. These sanctions meant that India, which had just liberalised its economy, would be cut off from all international developmental funding, especially by the World Bank. At that stage, the Indian economy was reasonably dependent on the global economy, especially for foreign exchange — which allowed it to pay its import bills.

Yashwant Sinha, the finance minister, took up the mantle of getting the economy running in the face of severe global sanctions.

“My mortal fear was that bleeding on the foreign exchange front would create all kinds of problems, and would create a real problem in our economy, as it did in 1991,” Sinha told ThePrint.

Overnight, the foreign developmental aid and private investments coming into the Indian economy dried out. Moreover, in case India faced an immediate monetary crisis, the doors to the International Monetary Fund were also shut.

Sinha devised a way out of this economic conundrum.

“We decided to approach NRIs (Non-Resident Indians) and PIOs (People of Indian Origin), through the Resurgent India Bonds, and raise foreign exchange funds through these bonds, which were backed by the State Bank of India,” he said.

Within 10 days, India received $4.5 billion.

In addition, the government worked towards increasing domestic demand via ramping up the national highway programme and rural road projects, and facilitating reforms in the information technology and telecom sectors, Sinha said.

Two-pronged diplomacy

But the economic sanctions and mounting global pressure on India led to the Vajpayee government adopting a two-pronged diplomatic approach.

On the one hand, India began negotiating with the US to get the sanctions removed. Jaswant Singh headed these negotiations from the Indian side and Strobe Talbott from the American side. The negotiations went on for two and a half years, with the duo meeting 14 times at 10 different locations, across three continents.

Vajpayee, meanwhile, began arguably India’s most ambitious diplomatic negotiations with Pakistan. In August 1998, began the Vajpayee-Nawaz Sharif dialogue.

Eventually, these two simultaneous diplomatic negotiations resulted in the removal of economic sanctions against India and Vajpayee visiting Pakistan to launch the Delhi-Lahore bus service.

Also read: Pokhran anniv: Vajpayee’s secretary recalls moment of tension & tears on nuclear test day