The trekking trip to Badrinath and the Valley of Flowers was meant to be a fun adventure for a group of 40 civil-servants-in-training. Instead, it turned into a dark chapter in the history of Indian bureaucracy.

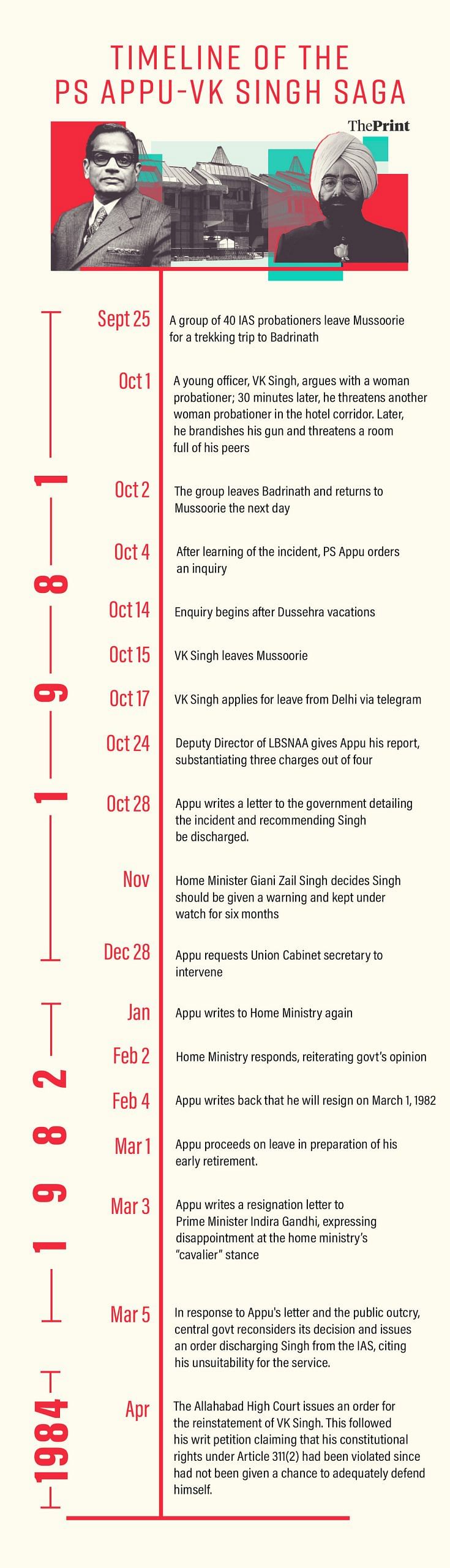

On 1 October 1981, in the dead of night at Badrinath, an inebriated IAS probationer named VK Singh pulled out a .32 calibre revolver, loaded with four bullets, and threatened his trekking companions. Later, he allegedly attempted to assault two women probationers in the group. With the added danger of inclement weather, the group cut the trip short and returned, shell-shocked, to the IAS academy in Mussoorie.

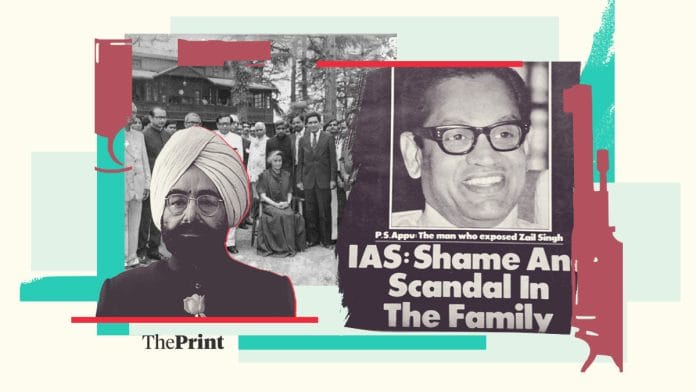

The scandal ripped through the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA), exposing a fissure that ran all the way to then Home Minister Giani Zail Singh’s office. Letters were sent off to the Prime Minister’s Office, senior politicians pulled strings, the matter was leaked to the press, Parliament erupted in uproar, and a moral panic descended over the bureaucracy.

Different versions of the story swirled. While the Indian Express hinted at an attempted rape, the Statesman concluded that the 29-year-old IAS trainee was a “pistol wielder but no rapist”. But all newspapers concurred that the incident was not taken seriously enough.

“The moral of the Mussoorie story is that we have debased standards of moral rectitude expected of our administrators,” pronounced the Hindustan Times.

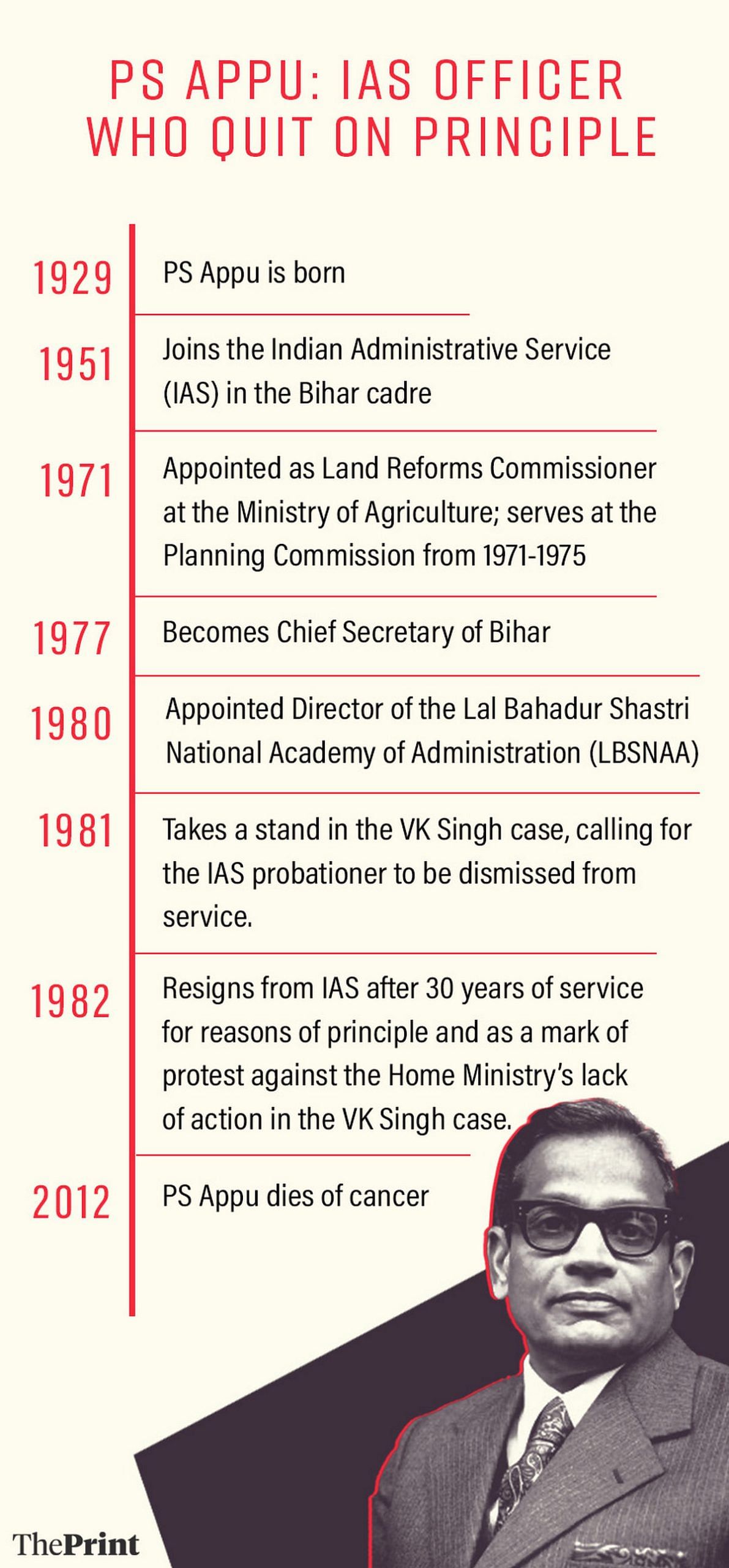

Fighting for strict action against the offender was senior IAS officer PS Appu, the director of LBSNAA. And when the Home Ministry decided to let VK Singh off with a slap on the wrist, Appu resigned in protest.

Appu’s stance was not over (VK Singh’s) indiscretion, but that as a young officer in his third month at the academy, he tried to use his influence and get rid of a director

-SM Vijayanand, 1981-batch IAS officer

“It is unusual for a civil servant, howsoever senior he is, to write directly to the Prime Minister,” he wrote to PM Indira Gandhi on 3 March 1982, six months after first raising the issue with the Home Ministry, which then oversaw the Department of Personnel. “I am resorting to this unconventional step because I see no other way to bring to the Prime Minister’s notice a case of grave misconduct on the part of an Indian Administrative Service officer and the cavalier manner in which the Home Ministry disposed of the matter.”

Appu warned that by failing to adequately discipline the probationer, the government was sending a dangerous message—that with “influence in the right quarters, one can commit even heinous crimes with impunity.” He also wrote that the Home Ministry’s decision would “have a disastrous effect on discipline and morale in the service in general, and at the national academy in particular.”

At a time when IAS probationer Puja Khedkar’s fraudulent qualification to the All India Services has called into question the integrity of the UPSC’s selection process, PS Appu’s legacy reflects the unyielding ethical backbone the services are supposed to represent. Appu’s legacy inspires a generation of IAS officers, setting the bar for the conduct expected of those joining the steel frame of the republic. But his kind of moral fibre is hard to spot in would-be IAS officers by simply deploying current service and selection rules. The Khedkar incident highlights the dire need for reforms. A tough exam, even one that sometimes has over a million applicants, is no guarantee of finding PS Appus.

“The bureaucracy is supposed to be the steel frame that upholds values. Officers like Mr Appu demonstrated that with their careers. We were lucky to have someone like Mr. Appu. He was a legendary officer who was deeply committed to the values that we have taken a vow to uphold,” said civil-servant-turned-activist Harsh Mander, who was at LBSNAA when Appu was director. “He kept emphasising that we have the space to follow our conscience, which is our right and duty as a civil servant — provided you’re ready to pay the price. That is what he demonstrated by stepping down.”

Baked into the drama was the fact that one of VK Singh’s companions on the trek had allegedly made derogatory remarks against him as an “uncivilised Bihari”. This may have contributed to the government’s hesitance to act decisively.

Also Read: Indian politicians hit the jackpot with 1957 TISCO case. It set the tone for political funding

An upstanding legacy

Retired IAS officer SM Vijayanand was part of the 1981 batch that witnessed the scandal unfold in Mussoorie. Forty-three years later, Appu’s words at the start of that academic year are still fresh in his mind.

“He told our batch — to work at banks, we have institutions like IIMs, IITs, PSUs. But there is only one institution working for the poor: the Indian Administrative Service,” said Vijayanand, who retired as chief secretary of Kerala. “I was straight out of college, and had held no other job. I heard him say that at the age of 24, and it was the one great clarity that stayed with me. He had a way of conveying values and principles without preaching — he was certainly preaching less than what he practised, so that speaks to his credibility.”

Appu was a civil servant whose reputation preceded him. Even those who never worked with him had stories about his integrity. Described by Harsh Mander in a tribute after his death in 2012 as “erudite and brilliant”, Appu inspired generations of IAS officers to stick to their principles no matter the consequence.

Born in 1929, Appu joined the Bihar cadre in 1951, rising through the ranks from collector in multiple districts to finance secretary and finally chief secretary. Appu’s response to being appointed as chief secretary in 1977 is legendary in bureaucratic circles— he wrote a long letter to Bihar Chief Minister Karpoori Thakur, explaining all the reasons why his appointment should be reconsidered. He even listed five other more senior officers he considered better suited to the job.

Mr Appu was a wonderful person. I recall he was friendly, open, and open to dissent. He was delighted by my disagreements, rather than put-off… we were bereft not having him (at the academy). And yet we realised that by his stepping down he was continuing his training of us

-Harsh Mander, IAS officer-turned activist

When Thakur insisted on his appointment, Appu wrote another letter laying out conditions before taking the job. The list included strict office hours for his employees, zero tolerance for political pressure, “ruthless action” against corruption, no interference in restructuring the administration, and the freedom to leave the moment he or the CM felt he was no longer effective.

“I did not lay down the above conditions because of my arrogance or any feeling that I was indispensable,” he’d explain in his writings, compiled in a book called the Appu Papers. “I did so because I felt that the situation in Bihar was so bad that there was no hope of effecting the necessary improvement unless those conditions were fulfilled.”

Appu also outlined his “personal interest” in these conditions—that he would lose his reputation if he could not be effective as chief secretary.

“If the conditions prevailing in Bihar during the last few years are allowed to continue even a superman will not be able to deliver the goods. And of course I am no superman,” he wrote.

Less than a year later, when he felt these conditions were not being met, Appu stepped down and took a central deputation as additional secretary in the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation. The pay cut didn’t deter him.

“When he found he was being let down, he voluntarily went from chief secretary to be additional secretary at a personal financial loss,” said Pradip Bhattacharya, who edited The Appu Papers and was deputy director at LBSNAA between 1979 and 1983. “That is the type of uprightness Appu projected throughout his life.”

Appu was also an expert on land reforms at a time when specialisation within the services was not as common. From 1971 to 1975, he served as the land reforms commissioner at the Ministry of Agriculture and the Planning Commission. In 1972, he found himself in headlines for saying that land reforms were failing in India because of the “lack of political will”.

His own will to stand for his convictions never budged. He became director of LBSNAA in August 1980 and had been at the academy for barely a year when the trekking incident occurred, leading to his resignation months later.

“Appu taught us what the power of the civil servant is—and not to fall for the arrogance of power,” said Vijayanand. “Corruption is rampant, he would say, and a great civil servant is one who knows how to choose his battles.”

Given his reputation, it was no surprise that the Mussoorie incident and its fallout became the battle Appu chose to fight. Disappointed that it had come to this, his parting remark to the faculty at LBSNAA was: “I leave to you the bricks and mortars of this Academy.”

Appu expressed his frustration at how “futile” his efforts to instill “values of professional competence, political neutrality, social commitment, fearlessness, impartiality, and integrity” had begun to seem.

A ‘futile’ battle

When the contingent of IAS trainees returned from their Himalayan sojourn on 3 October 1981, they brought back a harrowing tale. They claimed that VK Singh had gotten into a heated verbal exchange with two women probationers during the day and later unleashed his fury after drinking too much. It was alleged that at a dharamshala, he not only brandished a gun but also pointed it at the women’s heads. When they barricaded themselves in a room, he reportedly pounded on the door and screamed abuse.

When told about the incident, Appu ordered an internal inquiry. After receiving the report on October 24, he quickly shot off a letter to the secretary of the Department of Personnel—then under the Home Ministry—recommending that VK Singh be discharged from service.

Appu concluded that Singh lacked the “qualities of mind and character needed for the Indian Administrative Service”. This was not just based on the incident. The misbehaving probationer, it turned out, had also been “withdrawn” from the National Defence Academy over disciplinary issues in 1971, a fact Appu highlighted in his letter.

As the weeks rolled by without a response, Appu grew increasingly frustrated. On 28 December, he wrote again to the cabinet secretary and the secretary of the Department of Personnel, this time stating that if his recommendations weren’t accepted, he would step down as director.

In one of his letters, he also noted he’d been made aware of the “great deal of lobbying” that the probationer had done in Delhi’s power corridors to get a clean chit.

“Appu’s stance was not over (VK Singh’s) indiscretion, but that as a young officer in his third month at the academy, he tried to use his influence and get rid of a director,” explained Vijayanand. “And this is the reason why Appu wanted him dismissed.”

Finally, in February 1982, a reply came from AC Bandopadhyay, the secretary in charge of personnel. But it wasn’t what Appu was expecting: the government had decided to let VK Singh off with a mere warning.

This was just the tip of the iceberg. Questions swirled about why such leniency was shown, especially when other probationers had previously been dismissed for lesser offenses, like sending prank telegrams to peers’ parents.

It was whispered that VK Singh, who was from Bihar, allegedly had powerful political connections through his wife’s family to then-Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister VP Singh. There was also talk that he had appealed to Zail Singh for protection and had even met privately with the Home Minister in Delhi while on leave after the incident.

(VK Singh) belongs to a poor family, and it is only rarely that a poor man’s son makes it to the IAS. Secondly, only one of the four charges against him was proved beyond doubt. Finally, I only suggested postponement of the decision against him, because the director of the academy could terminate his probation if his conduct did not improve with time

-Zail Singh in a 1982 interview with India Today

In February 1982, Appu informed Bandopadhyay of his decision to retire prematurely, effective 1 March. He then wrote directly to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on 3 March, detailing the incident, his correspondence with the Home Ministry, and the troubling trend of probationers using political influence to get their way.

He expressed his frustration at how “futile” his efforts to instill “values of professional competence, political neutrality, social commitment, fearlessness, impartiality, and integrity” had begun to seem.

Somehow, the matter, including the letters, was leaked to the press, and it immediately caused a furore among the Opposition. On 5 March, it was taken up as a matter of urgent importance in the Lok Sabha, and a few days later in the Rajya Sabha. Zail Singh’s role, Appu’s resignation in protest, and the verification process for IAS inductees were all hotly debated.

In the Lok Sabha, Zail Singh changed his tune, announcing that a decision had been made to remove VK Singh after further deliberations. Speaking in Hindi, he remarked, “nowhere in the world is a decision taken and not reconsidered”.

Political uproar

For one afternoon hour, the VK Singh-PS Appu controversy raged in the Lok Sabha.

“He is one of the finest officers of the Indian Administrative Service. It is indeed a pity that this fine officer was sacrificed by the Home Minister in preference to a delinquent,” declared George Fernandes on the floor of the Lower House on 5 March 1982— two days after Appu sent in his resignation to the PM.

Baked into the drama was the fact that one of VK Singh’s companions on the trek had allegedly made derogatory remarks against him as an “uncivilised Bihari”. This may have contributed to the government’s hesitance to act decisively, ultimately leading them to opt for “reformist” rather than “deterrent” action.

Most civil servants would say that they are blameless and that the “dirty” politicians are responsible for the sorry state of affairs. This is really a case of the pot calling the kettle black…The major share of the guilt must be laid at the doors of the civil servants themselves

-PS Appu

“After all the boy belongs to a poor family, and it is only rarely that a poor man’s son makes it to the IAS,” Zail Singh told India Today at the time, justifying the government’s leniency. “Secondly, only one of the four charges against him was proved beyond doubt. Finally, I only suggested postponement of the decision against him, because the director of the academy could terminate his probation if his conduct did not improve with time. But it is a fact that VK Singh was sorry for his conduct and never misbehaved in future.”

However, in the Lok Sabha, Zail Singh changed his tune, announcing that a decision had been made to remove VK Singh after further deliberations. Speaking in Hindi, he remarked, “nowhere in the world is a decision taken and not reconsidered”.

Minister of State for Defence P Venkatasubbaiah also gave a long speech explaining the Home Ministry’s revised stance, now arguing that there was a need for the “highest standard of rectitude and character” in the IAS.

This shift apparently occurred that very day after Prime Minister Gandhi allegedly rapped Zail Singh on the knuckles. The safety of women officers was the sticking point, according to those with knowledge of the matter.

Will the Government apologise to this senior Administrative Service official, a man of integrity, a man of unimpeachable integrity and ability?… Or, will Government want to equate Mr Appu and Mr VK Singh with the same yardstick?

-George Fernandes in the Lok Sabha on 5 March 1982

Jaipur MP Satish Agarwal pointed out that the House had to be adjourned for two hours that morning while the Prime Minister and Home Minister discussed the matter.

From calling for “a reformative approach by issuing a strict warning to the probationer and keeping a watch over his conduct and behaviour” for the next six months, the government now recommended that Singh be discharged from service under Section 12(b) of the IAS (Probation) Rules.

The opposition, however, was not easily appeased.

“Will the Government apologise to this senior Administrative Service official, a man of integrity, a man of unimpeachable integrity and ability? Will government apologise to this man and get him back to his position — or to any position — but nevertheless get him back? Or, will Government want to equate Mr Appu and Mr VK Singh with the same yardstick?” Fernandes demanded.

Zail Singh demurred, but he had no issues with the Opposition praising the Prime Minister for stepping in and handling the matter.

“For justice, it is necessary for small crimes not to receive big punishments and big crimes not to be forgiven with small punishments. There’s injustice in both,” he said in Hindi. “He wasn’t let off — he was just punished lightly.”

The discussion also turned to the fact that VK Singh had previously qualified for another government service—Foreign Service (B) in 1978—before clearing the IAS exam in 1980, and could conceivably continue in that capacity.

“God save the women employees of the Indian Foreign Service!” exclaimed Dr Subramaniam Swamy.

On 8 March, the matter was also re-hashed in the Rajya Sabha. MoS Venkatasubbaiah insisted that the government had done due diligence in verifying the probationer’s background over the previous five years, but that making the process more “foolproof” was worth considering.

But in the end, all of this turned out to be moot. VK Singh challenged his discharge in the Allahabad High Court and won his case against the Government of India. He went on to serve as an officer in the AGMUT cadre.

Singh’s former colleagues described him as a “changed man, completely shattered” by that experience.

Crusading spirit

Amid the sensational news stories and political grenade-throwing, Appu’s predicament sent shockwaves through the bureaucracy. A group of bureaucrats—including EAS Sarma, Nirupama Rao, Meera Shankar, Ajay Shankar, and Sudhakar Rao—gathered at an office in the Ministry of Power to draft a statement in support of Appu in March 1982.

“Civil service needs a moral backbone. Everyone should realise they are responsible to the Constitution and the people at large,” said EAS Sarma, a 1965-batch IAS officer who also opted out from service in 2000 over political interference while serving as secretary in the Finance Ministry under the Atal Behari Vajpayee government. “It’s very important for senior officers to set an example to juniors. Today, many seniors are caving into political pressure, compromising their self-interest. In the process, it’s demoralising junior officers. To be upright, effective, and go by the rule book is broadly the Appu legacy.”

You tend to keep such examples (as Appu) in your mind. The real need today is to have people like Appu leading the civil services

-EAS Sarma, former secretary in Finance Ministry

But under the Narendra Modi government, the bureaucracy has been going through a period of churn, with changes being made to the rules of recruitment through lateral entries and a greater political hand in appointment and transfers.

Sarma cited Appu as the “subconscious” inspiration behind his own voluntary resignation over serious differences with the PMO on policy matters. Since then, too, Sarma has remained vocal, including speaking out last year against the Narendra Modi government’s use of IAS officers for political activities.

“You tend to keep such examples (as Appu) in your mind,” said Sharma. “When I look back, I think I did the right thing at the time. The real need today is to have people like Appu leading the civil services.”

Appu didn’t stifle his voice against injustice after voluntarily retiring. The Appu Papers, edited by Bhattacharya, are full of his principled stances and his passion for social issues.

After the 2002 Godhra riots, Appu wrote an open letter to the President of India. In it, he decried the fact that civil servants had failed in their duty by allowing the riots to take place and expressed his deep concern about the civil service losing its independence and caving to political pressure. He demanded the dismissal of the state government, the dissolution of the assembly, and the imposition of President’s rule. He then travelled across India, meeting with bureaucrats in various states to consult on the state of affairs.

“He put the crime on the civil servants who colluded,” said Vijayanand. “He always felt that if a civil servant can’t stand up and say that something is wrong, they have failed. We all imbibed his values.”

A relentless crusader against corruption, Appu was unsparing in his criticism of the political class. In his writing, he linked the exponential growth in corruption and criminalisation in India to the rise of Sanjay Gandhi in the 1970s — which, he argued, led to the undermining of institutions and a promotion of crony capitalism under the permit license-quota raj.

He was also critical of Lalu Prasad Yadav, and wrote that he had distorted priorities despite being a decisive leader with a popular support base.

He had several ideas on reforming governance, from downsizing government to creating and then strengthening a Lok Pal system.

“Most civil servants would say that they are blameless and that the “dirty” politicians are responsible for the sorry state of affairs. This is really a case of the pot calling the kettle black…The major share of the guilt must be laid at the doors of the civil servants themselves,” wrote Appu in a scathing essay on reforming the bureaucracy. “The unpleasant truth is that in most cases the civil servants have active collaborators, and not just silent spectators or reluctant accomplices in ruining the civil service.”

But he hastened to add that the bureaucracy is not an autonomous institution — and that civil servants represent a cross-section of the population.

“When the polity is in decline and the society in disarray, as in India today, it is inevitable that the bureaucracy too should be in a bad shape,” he concluded in the same essay. “Hence efforts towards reforming the bureaucracy will be of no avail until the grave’ maladies in the body polity are set right. The first step in that direction should be conscious, well-concerted efforts to develop accountability in our policies.”

Also Read: The many avatars of Manoj Soni—‘Chhota Modi’, UPSC chairman, now monk in obscure sect

A tough act to follow

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi gave Appu an appointment in Delhi after he submitted his resignation letter. He arrived at her office and waited. After about 30 minutes of waiting, he got up and left.

“That is the type of no-nonsense man he is. He would never kowtow to power. He was let down comprehensively by the establishment,” said Bhattacharya.

Vijayanand noted that all probationers receive foundational lessons on the core values of the civil services—neutrality, anonymity, and integrity—but Appu gave them his own spin. “These values are foundational to the services,” said Vijayanad. “But how (Appu) explained them was unique. For example, he said that one can’t be neutral when the poor are affected. We were all taken aback by his example of integrity, too — he said that what exemplifies integrity is when you are able to say that another is better than you.”

Another legacy was Appu’s insistence that civil servants maintain a holistic view of all issues—especially regarding development and land reforms, areas in which he was an expert. He advocated a triangulation approach, advising that one should consult multiple perspectives—an expert, someone from a right-wing background, and someone from a left-wing background—before forming an opinion on a scheme or policy.

Many civil servants have anecdotes about Appu’s personal touch at the academy. For instance, he scrapped the requirement for wearing blazers at the academy after hearing that someone had pawned their belongings to buy one. He encouraged learning culinary etiquette only to reject it. And once, when a probationer from Kerala fell sick, Appu paid for the 70-hour train journey back to Trivandrum and also sent an instructor to accompany him during the trip.

“His resignation from service prematurely on a matter of principle as director of the Academy had sent ripples through the Union Ministry and the entire bureaucracy and has left a lasting impact on our minds till date,” wrote IAS officer Anita Agnihotri, part of that fateful 1980 batch, in 2008.

“Mr Appu was a wonderful person. I recall he was friendly, open, and open to dissent. He was delighted by my disagreements, rather than put-off,” said Mander, who first raised the issue of mandatory blazers and coats to Appu in 1980. “By the time we came back to Mussoorie after district training, we were bereft not having him there. And yet we realised that by his stepping down he was continuing his training of us.”

But in the immediate aftermath of Appu’s departure, the academy went through several years of instability, with four directors coming and going until BN Yugandhar took charge in 1988 for a five-year term.

Several IAS officers described Appu’s immediate successor, who took over in May 1982, as “ineffective” and “having a glad eye”. He was removed after just four months.

“The new director who came after Mr Appu was a different model,” recalled Vijayanand.

That summer, when Prime Minister Gandhi visited the academy to assess its progress, all the male probationers sat on a rug by her feet. But echoing Appu’s spirit of dissent, not a single female officer-in-training came to meet her.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Please read the Allahabad High Court order.

The link is https://www.casemine.com/judgement/in/5ac5e2b94a932619d9020ab7

Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar, the leader of the Bar, appeared pro bono in this case. The entire post praises Mr. Appu.

Is it not interesting that V.K. Singh hailed from Bihar, and Mr. Appu was from the Bihar cadre? Mr. Appu preferred to desert the cadre because of animosity with V.K. Singh’s father-in-law, a chief engineer and a powerful technocrat.

In Mussoorie, Appu got an opportunity to settle the score. V.K. Singh, who came from a modest background, was an exceptionally bright student.

The then Home Minister Giani Zail Singh emerged as the most intelligent person in the episode to consider the case on merit, not on the media trial. The victim, Vrinda Swarup, an IAS probationer, was from an elite background and had cast aspersions on the modest background of V. K. Singh, causing (unjustified) annoyance of Singh on the spur of the moment.,.

I have seen VK Singh as a desolate, bereft and depressed young man in the office of his advocate.

A well-drafted story. Kudos to the writer.

The lady probationer who stared down the gun barrel without flinching contributed enormously to the education sector.