Everywhere, fruit trees were limp on the ground, wantonly cut down, all covered with buds”, the letter from the killing fields of the Somme recounted. The medieval homes in the town of Pérrone, France had been set on fire. Nearby, an entire village had been razed. “The surroundings are indescribably desolate and dotted with small crosses,” another letter read. “We haven’t many dead in the trenches—at least only one decapitated unfortunate has been discovered below the surface—but those outside could well do with some loose earth over them.”

The clay soil had been dredged up by years of shelling and turned into an indescribable mush. “The trenches were in a filthy state owing to a more or less futile attack made by our men the night before,” Lieutenant George Mallory recorded in another letter home, written in 1916. “I don’t object to corpses so long as they are fresh. With the wounded, it is different.”

An end as ashes and dust, Mallory wrote, he was prepared to accept. “To return to clay would indeed be a sort of immortality,” he wrote to his wife, Ruth Mallory, “but not one that I embrace, not if it were wet clay.”

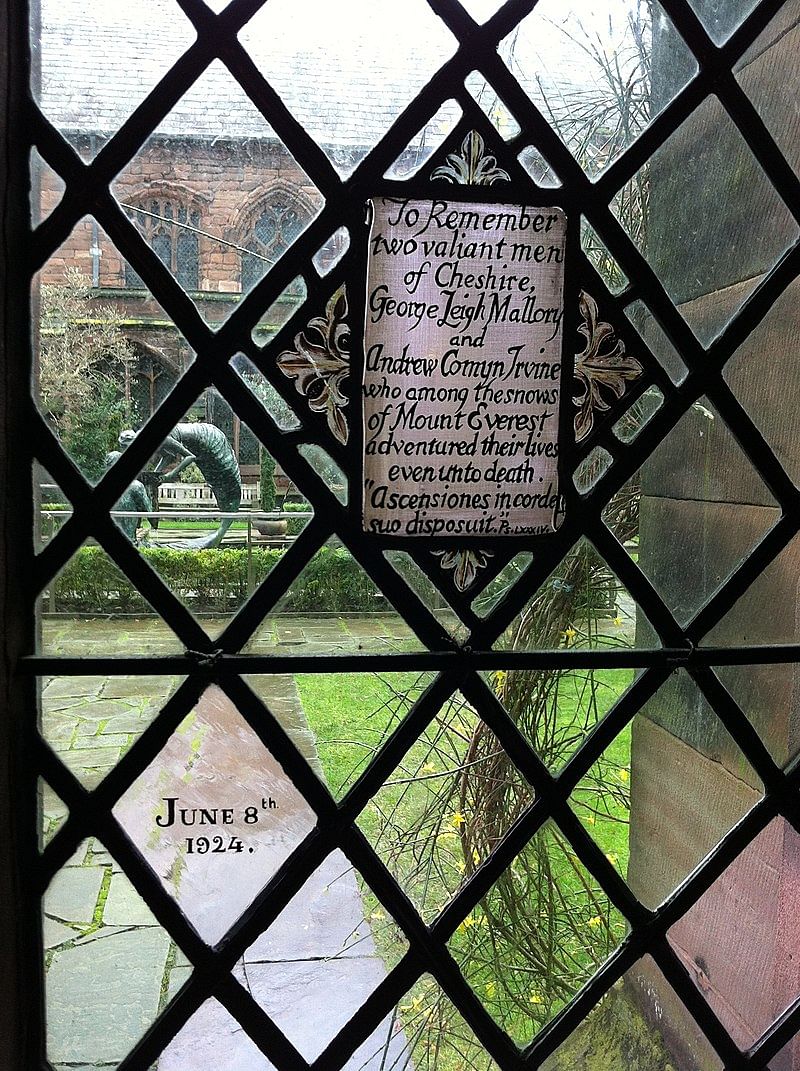

Early one morning in June 1924, one hundred years ago, Lieutenant Mallory—one of the world’s greatest mountaineers—set off with his climbing partner, Andrew Comyn ‘Sandy’ Irvine, to summit Mount Everest. Two days later, on 8 June 1924, two dots were seen on a high ridge by fellow climber and English geologist Noel Odell, moving toward the top.

Then, mist closed over the mountain.

I noticed far away on a snow-slope leading up to the last step but one from the base of the final pyramid, a tiny object moving and approaching the rock step. A second object followed, and then the first climbed to the top of the step. As I stood intently watching this dramatic appearance, the scene became enveloped in cloud – Noel Odell, geologist and mountaineer

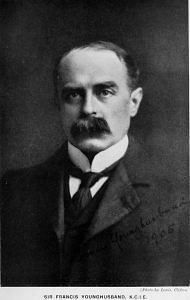

Francis Younghusband, the legendary adventurer who organised the expedition, conceded in a 1920 lecture that there was “no more use in climbing Mount Everest than in kicking a football about or dancing”. That said, its purpose was to persuade men “they were getting the upper hand on the earth, and that they were acquiring a true mastery of their surroundings”.

The one-time history schoolteacher Mallory proved to have a more enduring explanation for why he wanted to climb Everest: “Because it’s there,” he told a journalist in Philadelphia.

Everest, though, wasn’t just there. The story of the tragic effort to climb it wasn’t simply one of macho heroism, pitting man against nature. Instead, imperial hubris, racism, and the hideous slaughter of the First World War all shaped and drove the project.

We have on our northern borders the greatest mountains in the world and yet owning to various obstacles of reasons, we know next to nothing about them – George Curzon, Viceroy of India

A hundred years on, Nepal’s courts have ordered limits on the number of permits issued to climbers seeking to scale Everest, amid rising evidence of environmental damage. Films of gargantuan queues of climbers—most paying thousands of dollars to be escorted up the mountain by professionals—have made Everest mountaineering seem more like visiting an amusement park than a heroic contest testing the limits of human achievement.

The French philosopher Michael Serres famously observed that all animals, including humans, use pollution as a means of marking their possession of space. Animals mark their territory with urine, faeces, or other signs, asserting it’s theirs. The true legacy of Younghusband and Mallory is the nylon rope, plastic waste and filth that marks the path from Base Camp to Everest. The hundredth anniversary of his climb ought to be a time to reflect on how best to obliterate its physical legacy.

The Empire and Everest

Led by the infantry officer William Lambton, the East India Company had begun the Great Trigonometrical Survey in 1802, seeking to map India. Together with spies and explorers, historian Riaz Dean has written, map-making was a critical instrument to secure the jewel in the crown. From 1830 to 1843, the geographer George Everest took charge of the project as surveyor-general of India, pushing the Great Trigonometrical Survey’s cartographers to painstakingly traverse the giant arc from Cape Comorin to the Himalayas.

The project’s costs and the sheer effort involved, the scholar Matthew Edney has written, were not justified by its immediate utility. For the East India Company, Edney concluded, the Great Trigonometrical Survey was also “a key symbol, signifying not only British political and imperial control but also British cultural superiority”.

The final conquest of the mountain has become practically a national ambition, Percy Cox, Everest Committee chairman

Local names were systematically used to designate mountains and other significant geographical features, as if to establish the Empire’s intimate knowledge of its colony. There were two mountains, though, which defied the project of colonial knowledge-gathering.

Karakoram Range, Peak Two, some 50 kilometres up the Baltoro Glacier, and the second highest in the world, had never been given a local name and never got one. The other, Peak XV, discovered by the mathematician Radhanath Sikdar in 1852, was on the borders of Nepal and Tibet, both closed to the British. Even though George Everest never laid eyes on the mountain, it was named in his honour.

From 1899 onwards, George Curzon, viceroy of India, had begun discussing the idea of an expedition to Everest with friends, mentioning that he intended to seek permission from the Maharaja of Nepal for an expedition. Nothing came of the effort. The idea fructified during discussions with Younghusband, historian Gordan Stewart has recorded, around 1903-1904. The flamboyant Younghusband had already made a reputation for himself, travelling from China to India through the fabled silk-route city of Kashgar and over the Karakoram in 1887.

Gazing at the mountains from his lodge in Shimla, Curzon complained: “We have on our northern borders the greatest mountains in the world and yet owning to various obstacles of reasons, we know next to nothing about them.” The viceroy, Stewart records, wished “a thoroughly competent party sent out.”

Later, according to Stewart, in a 1905 letter, he reproached Douglas Freshfield, the president of the Alpine Club: “With the two highest mountains in the world for the most part in British territory, we, the mountaineers and pioneers par excellence of the universe, make no sustained and scientific attempt to climb to the top.”

The issue of access to Everest was soon resolved by Younghusband. In 1904, he led a military expedition into Tibet, claiming to counter a non-existent threat from Russia. The clash between the most powerful empire in the world, and one of the planet’s weakest countries, ended with upwards of 2,000 Tibetans killed, the historian Charles Allen has recorded. Though Curzon was privately appalled at Younghusband’s conduct—and the risks the Empire might become responsible for governing a low-revenue province—he rewarded the officer by making him the imperial resident for Kashmir.

Little came, immediately, of Younghusband violently throwing open the gates to Everest, though. The Royal Geographical Society, Stewart explained, was focused on the race to the South Pole, and many in its ranks were sceptical of the scientific value of mountaineering.

Following the First World War, though, Younghusband became president of the Society and was determined to make climbing Everest the centrepiece of his tenure. Two years later, in 1921, a committee was formed to organise the first expedition.

Then, according to writer and explorer Charles Wade , the thirteenth Dalai Lama sent orders to his provincial officials in April 1921: “The British Government has deputed a party of Sahibs to see the Chha-mo-lung-ma mountain [as the Tibetans referred to Everest]. They will evince great friendship towards the Tibetans. The Great Minister Bell has asked us to issue an order to the effect that these Sahibs may be supplied with riding ponies, pack animals and coolies.”

The war had knocked the ball floor from under middle-class English life – Stephen Spender, author and poet

Any other assistance, the order recorded, “that the Sahibs may require either by day or by night, on the march or during halts, should be faithfully given in the best possible way in order to maintain friendly relations between the British and Tibetan governments”.

The bayonets of the Raj had prepared the path for the ascent of Everest.

Also read:

The man and the mountain

Lytton Strachey—brilliant Bloomsbury intellectual and author of the iconoclastic book, Eminent Victorians—voiced the sexual reverence many seem to have felt in Mallory’s presence: “Mon Dieu! George Mallory!”, he wrote after they first met Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister. “My hand trembles, my heart palpitates. He’s six foot high, with the body of an athlete by Praxiteles and a face—oh incredible—the mystery of Botticelli, the refinement and delicacy of a Chinese print.”

Though Strachey’s homosexuality—no small crime in the era before the Second World War—did not become public until Michael Holroyd’s biography was published in the 1960s, it was common knowledge among his friends.

Mon Dieu! George Mallory! My hand trembles, my heart palpitates. He’s six foot high, with the body of an athlete by Praxiteles and a face—oh incredible—the mystery of Botticelli, the refinement and delicacy of a Chinese print – Lytton Strachey, author

For decades, historians have speculated that homoerotic attraction might have drawn Mallory to the closed, male world of mountaineering. But there is little to support the hypothesis. Erotic relationships between men were commonplace among the Edwardians, though few would have characterised themselves as homosexuals, in a modern sense. There is little doubt Mallory had homoerotic encounters at his boarding school and experimented sexually at Cambridge.

There is little evidence, though, that Mallory was homosexual. At 37, he was a devoted father and husband. From Mallory’s own writing, it is clear he saw mountaineering as a kind of raw spiritual experience. “A great mountain is always greater than we know: it has mysteries, surprises, hidden purposes; it holds always something in store for us. One need not go far to learn that Mont Blanc is capable de tout. It has greatness beyond our guessing, genius, if you like.”

The mountain was, in other words, a kind of pagan god; a mystery to replace organised religion, which Mallory had long rejected. The New Testament, he told his wife, in response to her growing religiosity, “I regard simply as a fallible human record of a wonderful man, which I understand, or try to understand, in its historical setting.” He had “no respect for the Church as divinely instituted”. The church had emerged simply as gatherings of early Christians, Mallory went on, of no greater intrinsic worth than “a universal Shakespeare Society”.

Likely, this rejection of institutionalised religion deepened because of the experiences Mallory had of the trenches—and the rebellions of many in his circle against the establishment that had led them into it.

Educated, like Mallory, at Cambridge, Siegfried Sassoon had fought in the Somme, gaining a reputation for his mastery of the savage art of raiding enemy trenches at night. He earned the Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order—one of which he later allegedly tossed in a river—but stunned the British establishment by writing a powerful anti-war manifesto.

In “an act of wilful defiance of military authority”, Sassoon’s 1917 protest statement was issued on behalf of soldiers “who are suffering now”. “I make this protest against the deception that is being practised on them. Also, I believe that I may help destroy the callous complacence with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realise.”

To avoid the inevitable scandal a military court-martial would cause, Wade recorded, the government agreed to a compromise suggested by the poet and writer Robert Graves. Sassoon was declared mentally unfit and dispatched to Craiglockhart, a military hospital in Edinburgh that specialised in the treatment of officers suffering from shell shock. The record would state that Sassoon suffered from hallucinations and nightmares—which he did.

I make this protest against the deception that is being practised on them. Also, I believe that I may help destroy the callous complacence with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realise – Siegfried Sassoon, war poet

Graves, Mallory’s lifelong friend, almost certainly discussed the issue. In 1921, Mallory resigned from his job at Charterhouse, a school where he had taught since leaving Cambridge a decade earlier. There was, however, a more fundamental break: A memorial service where the headmaster sat proudly when Field Marshal Herbert Plumer remembered the war as “a complete vindication of the English Public-School training in enabling inexperienced soldiers to take responsible posts successfully”.

Listening to the speech, Wade wrote, Mallory remembered Sassoon’s poem:

You smug-faced crowd with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go

“The war had knocked the ball floor from under middle-class English life,” wrote Stephen Spender. “People resembled dancers suspended in mid-air yet miraculously able to pretend that they were still dancing.” Mallory was no longer prepared to do so.

Also read:

The whiteness of Everest

Early in 1925, just weeks after Mallory and Irvine disappeared on Everest, bureaucrats at the India Office in London were invited to watch the silent film that recorded their expedition, The Epic of Everest. Large parts of the film were devoted to the expedition’s contact with Tibet. Each screening was preceded by a group of Tibetan Lamas performing music, chants, and dances. The official programme claimed, according to historian Peter H. Hansen , that this was “the first time in history that real Tibetan Lamas have come to Europe”.

To the Tibetans, for whom Everest was a holy site, and the Lamas sacred figures, this was an insult. Their ineffectual protests were ignored.

Even though the world of the Everest climber was a refuge from trauma, however, it was a distinctly White world. There was no equality or intimacy between Sherpa and Sahib. Lieutenant-Colonel EF Norton, the leader of the 1924 attempt, Stewart recorded, observed that “it is a curious psychological fact that there are men on the spot who could climb Everest without turning a hair. Yet the Sahib—so physically inferior in this respect—has come thousands of miles to give him a lead”.

Younghusband, following the 1922 expedition, described the expedition in similar terms, according to Stewart. “Englishmen have taken these men on to the very highest mountain and have persuaded them to carry a tent to no less than 27,000 feet…they have shown these men what they are capable of doing and have made them proud of themselves.”

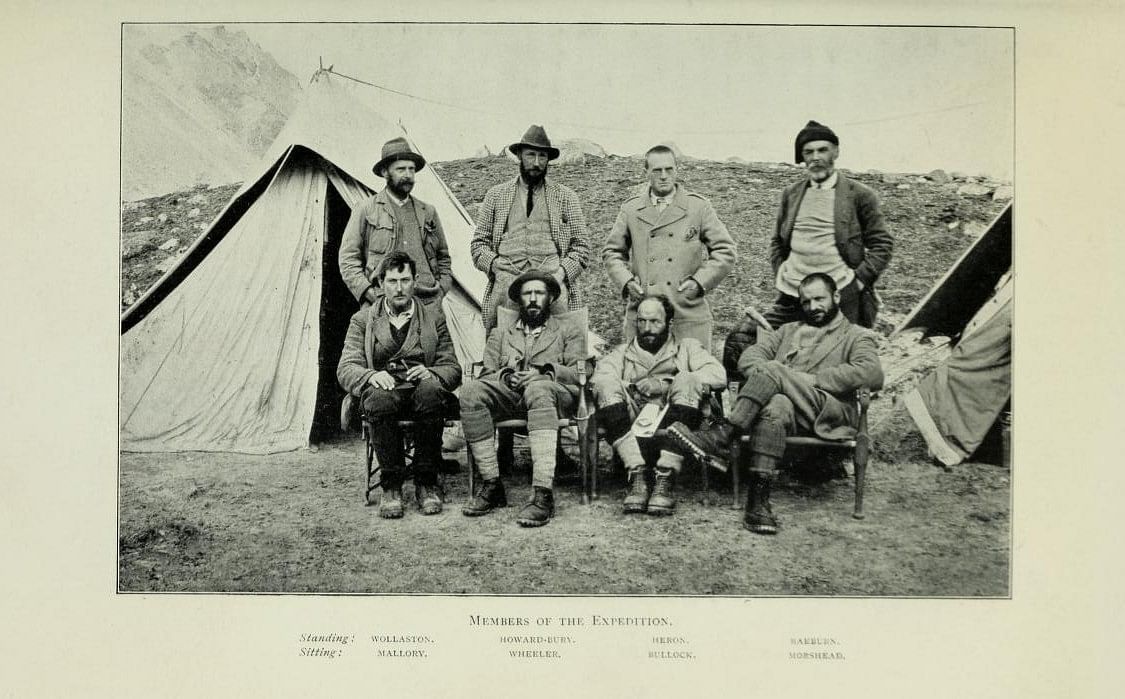

Focused on locating a route to the North Col, the 1921 expedition created considerable anxiety among Tibetans. Lieutenant-Colonel CK Howard-Bury recorded: “In these out-of-the-way parts they had heard vaguely of the fighting in 1904, and they imagined that our visit might be on the same lines. They imagined, too, that all Europeans were cruel and seized what they wanted without payment.”

As per Howard, a local official requested Lhasa: “As the people of this country are poor, I would request that you kindly approach the British with a view to effecting an early removal of the Sahibs from this place, so that they may not settle down permanently.”

There was also class. Stewart’s work shows that the expedition reconstructed the English society that the First World War had torn down, its members bound together by ties of education at public schools and Oxbridge. Mallory himself, of course, was educated at Winchester and Magdalene College, Cambridge. Irvine went to Shrewsbury and Oxford and rowed at the Henley Regatta. Andrew Irvine grew up in a home with a tennis court, croquet lawn orchard and kitchen garden.

Throughout the march across Tibet in 1924, Stewart notes, the members of the expedition kept up with news of the boat race.

Englishmen have taken these men on to the very highest mountain and have persuaded them to carry a tent to no less than 27,000 feet…they have shown these men what they are capable of doing and have made them proud of themselves – Francis Younghusband, explorer, author and British Army Officer

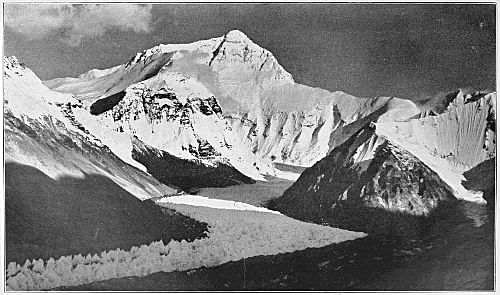

General Charles Bruce, writing before the 1924 expedition, described the project in terms Mallory might have inspired: “It is possible that certain branches of science may benefit from the experiences of the party, but the dominant note of the whole undertaking, first, last, and foremost, is a great adventure almost now become a pilgrimage. Did we not explain to the lama of the Rongbuk, the Sang Rimpoche, that it was for us an attempt to reach the highest point on earth as being the nearest to heaven?”

There was also wealth, though. Noel Odell had formed Explorer Films Ltd. with Younghusband as chairman, which was paid an incredible £8,000 for the film and photographic rights. The London Times threw in another £1,000 for the right to publish the expedition’s despatches. Odell was to have staged a number of stunts, like driving a Citroen-made tractor into Tibet.

And there was Imperial prestige. “The final conquest of the mountain has become practically a national ambition,” Percy Cox, the Everest Committee chairman would write to Secretary of State Samuel Hoare in 1934. “It would be a national humiliation were the final ascent to be allowed to pass to the nationals of any other country by reason of any slackening of interest on our part or lack of vigilance in our quest for the opportunity for the despatch of another expedition,” he said.

There is a story, missing from the records: The story of the brown bodies that bore White Sahibs up the mountain. “The coolies had behaved in the gamest fashion,” Mallory recorded in his account of the 1921 reconnaissance expedition, which sought out the routes to the mountain. “Three fell out in a state of exhaustion, and made their own down…The party straggled badly. But time was on our side, and gradually the eleven remaining loads arrived at their destination.”

Like the accounts of other Sahibs, Mallory’s story made no mentions of the names of the coolies; nor did he see reason to learn of their lives. Tejbir Bura, the porter who accompanied George Finch and George Bruce on the second summit attempt in the expedition, was given the task of hauling two additional oxygen cylinders as high as possible; he was not to have an opportunity to reach the top.

The Royal Geographical Society journal noted that seven porters were killed in an accident in the third summit attempt made in 1922 that was led by Mallory. The porters were not named.

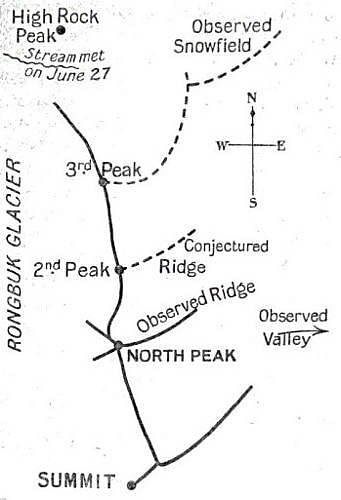

“At 8.40 on the morning of June 6, in brilliant weather,” Odell would record, “Mallory and Irvine left the North Col Camp for Camp V. They took with them five porters carrying provisions and reserve oxygen cylinders.” The next day, Mallory’s four porters arrived from Camp VI, “bringing me a message which said that they had used but little oxygen to 27,000 feet, that the weather promised to be perfect for the morrow’s climb.”

From 26,000 feet, Odell watched: “I noticed far away on a snow-slope leading up to the last step but one from the base of the final pyramid,* a tiny object moving and approaching the rock step. A second object followed, and then the first climbed to the top of the step. As I stood intently watching this dramatic appearance, the scene became enveloped in cloud.”

Even though Mallory might have loathed the values of the Empire that had led it to slaughter, he ended up giving his life to a project designed to reconstruct its moral legitimacy across the world.

Also read:

Lessons from the top

Embarking on his experiment to farm beans at Massachusetts’ Walden, the American naturalist Henry Thoreau wondered whether he had the authority to compel the earth to yield what he wished, rather than its ancient, wild abundance of millet grass, cinquefoil, and blackberry. Thoreau worried that he had made Walden woods less wild—that he had inhibited its freedom, dominated it, subjected it to his will, bent it to his own ends, domesticated it.

The story leading up to the death of Mallory and Irvine a hundred years ago shows the impulse to conquer ran through it: The war of 1914-1918, the imperial project, and the urge to climb Everest were united in seeking to subjugate other peoples, things and nature itself.

The coolies had behaved in the gamest fashion…Three fell out in a state of exhaustion, and made their own down…The party straggled badly. But time was on our side, and gradually the eleven remaining loads arrived at their destination – George Mallory, mountaineer

Humans have taken the marking of earth by pollution, to levels inconceivable by any other species. Fertilisers poison our rivers, plastics our oceans, and pesticides the soil. Everest has been reduced to a glorified garbage heap, strewn with the detritus of civilisation. The next frontier to fall will be outer space: “Because it’s there,” as Mallory said of the mountain he died on.

In 1999, Mallory’s mummified body was retrieved from the ice, with signs of injuries suggesting he was killed in a fall. He was buried, finally, on Scree Slope, a band of yellow limestone bearing marine fossils, which can be seen from the North Base Camp. Irvine’s body has never been found. The time has come to leave Everest—and the little other wilderness that remains—alone, and end the enterprise that has cost the earth too much.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

Excellent piece, Praveen.

Mr. Swami,

There is a typo in your article. It says Mallory started 100 years ago in June 2024. This date has not happened yet.