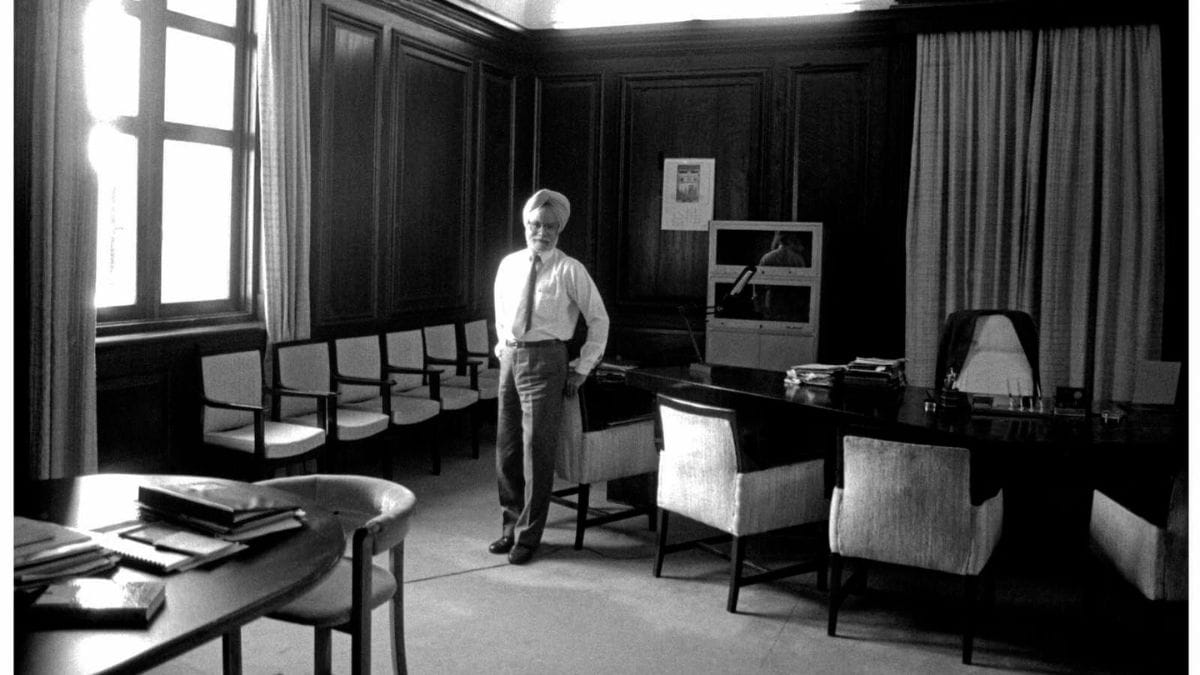

New Delhi: The story of India’s economic history is a tale of two economists—Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis and Manmohan Singh. And two key moments stand out: the Second Five-Year Plan of 1956 and the liberalisation of 1991.

The report card for the Mahalanobis model came 35 years later, in 1991. And India took a sharp and screeching turn.

Now, it is 35 years since Manmohanomics.

Both milestones shaped India’s political economy for decades. Both were implemented by finance ministers who were also economists and former RBI governors. Both battled political contestation. And in a way, both models failed because India didn’t follow them to their completion.

In the 1950s, PC Mahalanobis provided the blueprint, and Jawaharlal Nehru adopted it. In the 1990s, Manmohan Singh as finance minister championed reforms under the leadership of PV Narasimha Rao.

While the two approaches were radically different, standing at either end of the ideological spectrum, they each set out to meet India’s political reality halfway. At their core, both sought to tackle unemployment, foreign exchange crises, and industrial growth.

In 1991, as in 2025, the report cards of these two economic trajectories remain underwhelming. Unemployment is a problem, and so is manufacturing and industrial investment.

But as economists see it, politics got in the way each time.

Manmohan Singh’s reforms didn’t have political consensus. And Mahalanobis’ vision was an intellectual exercise that Jawaharlal Nehru—the strong, unquestioned leader—chose to implement the way he wanted. It’s why John Matthai, one of Nehru’s earliest finance ministers, resigned.

An underlying strategy of a robust public sector coupled with import substitution industrialisation was central to Nehru’s vision. It was the chosen path of that era—and was feted globally by economists and policymakers alike. In India, that vision birthed the Mahalanobis model in 1956, with the Second Five-Year Plan.

As historian Nikhil Menon notes, this policy passed into orthodoxy but remained unchallenged until the liberalisation reforms of the 1990s, when India was backed against the wall, staring at a balance-of-payments crisis that could relegate it to a growing list of “failed democracies.” The world was changing after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Mahalanobis way of economic thinking had outlived its shelf life.

“In the 1950s, the state had a clear idea on how to build the economy. In the 1990s, the state was trying to remove itself from the business of running businesses. Today, the state isn’t showing either of these two things — there’s a slide-back both in terms of economic policies and implementation,” said economic journalist AK Bhattacharya, the editorial director at Business Standard.

- Two pivotal economic moments: The Second Five-Year Plan (1956) by Mahalanobis and the liberalisation reforms (1991) by Manmohan Singh reshaped India’s political economy.

- Ideological divergence: While radically different, both approaches aimed to address unemployment, foreign exchange crises, and industrial growth.

- Role of politics and PR: Political contestation and deliberate public narratives shaped the implementation and perception of both models.

- Legacy and parallels today: Despite shifts in policies, challenges like unemployment and manufacturing persist, with debates around the role of expertise and political decisions.

The PR of planning

The narrative-building around both economic shifts was deliberate and comprehensive. In both moments, the government needed to convince the public that dramatic change was necessary and beneficial.

The first Kumbh Mela in independent India, held in 1954, was more than a spiritual gathering—it became the perfect ground to sell the Second Five-Year Plan to the Indian public.

Around 50 lakh people attended the Kumbh Mela, where the grounds were divided into zones, featuring stalls that distributed pamphlets and screened films. The Five-Year Plan Publicity Organisation had one clear mission: to convince the entire country that this was the way forward.

In the 1950s, the state had a clear idea on how to build the economy. In the 1990s, the state was trying to remove itself from the business of running businesses. Today, the state isn’t showing either of these two things

—AK Bhattacharya

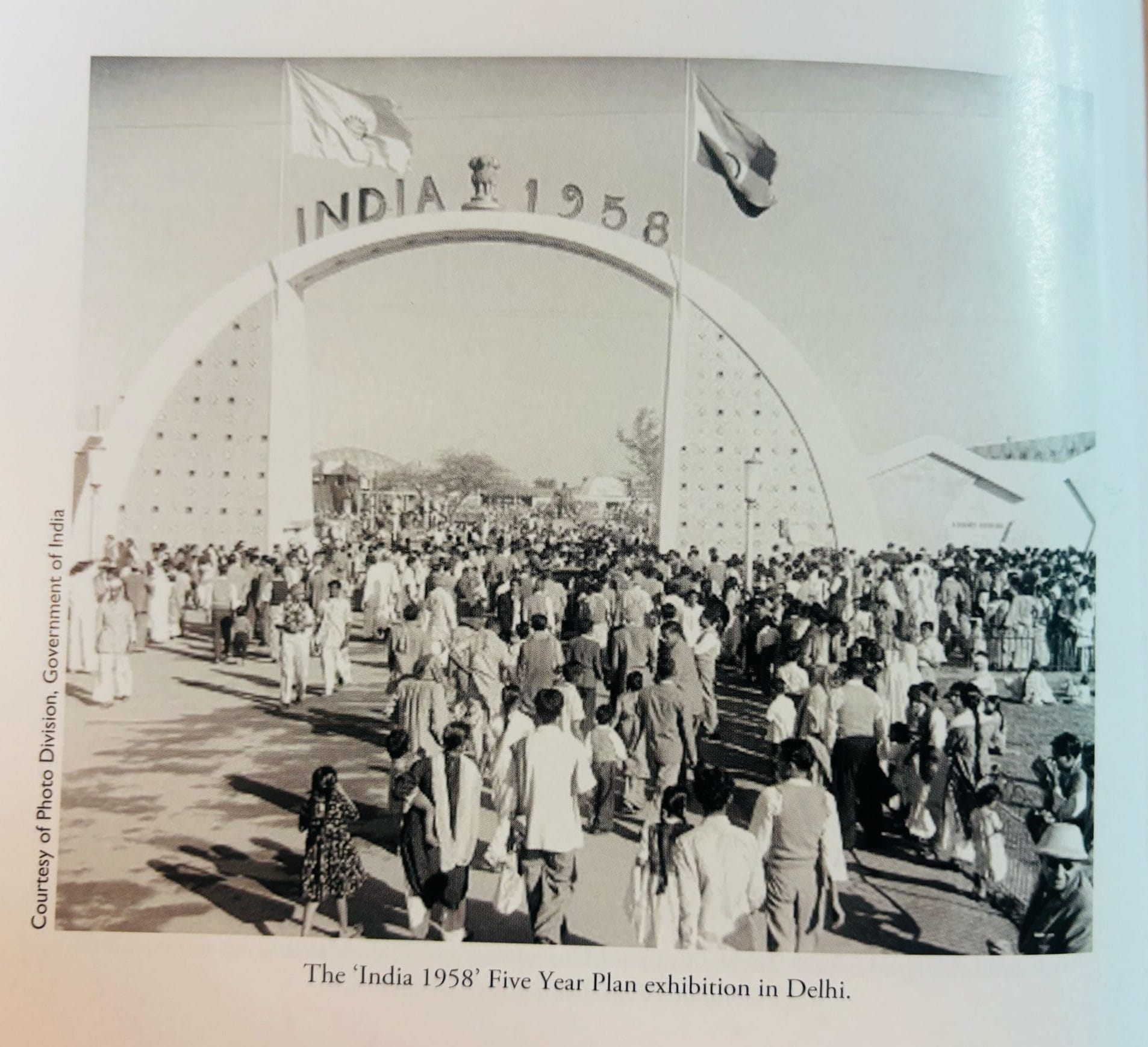

In the 1950s, the narrative was all about uniting to build a modern nation. There was a strong emphasis on technology, science, statistics, and large industries—all seen as pathways to the future. Stamps were issued, articles written, and cartoons drawn. The government even organised The ‘India 1958’ Five-Year Plan exhibition, which ran for two months in Delhi. Crowds flocked to Pragati Maidan, where the exhibition had four entrances: Gateway of Progress, Gateway of Commerce, Gateway of Science, and Gateway of Industry. Roads named “Yojana Path” (Plan Avenue) led to the Vikas Vatika (Garden of Development). The overarching message: India was an “ancient nation in the throes of regeneration,” as Menon describes in his book.

The outreach continued: books were published, and field officers were dispatched door-to-door to visit at least 16,000 locations. By 1963, official estimates claimed that approximately 2.3 crore people had been reached. Around 21,000 films on planning were screened, 22,000 public meetings and group discussions were held, and 4,000 drama and song performances were conducted by 83 field units.

By the 1990s, when change was needed again, the PR machinery swung into action once more. Countless newspaper articles were written heralding the change, portraying a young, new, modern India that was keeping up with the West. Rajiv Gandhi’s dedication to bringing in imports—which many say he didn’t have the gumption to follow through politically—was finally paying off, having prepared an Indian public for consumerism, elevating symbols like blue jeans and soft drinks. Like Singh famously said in Parliament while presenting the 1991 Budget, “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come.”

The government had to spin the reforms as necessary—and it was a bitter pill to swallow for both the Congress and for the Indian public, which had for so long followed the Nehruvian ideals of economic growth. Singh commissioned a report from economists Jagdish Bhagwati and TN Srinivasan to analyse the change liberalisation had brought to the economy, which the ministry published widely in 1993.

“The reforms had long been seen to be necessary, though the “political will” to start and sustain these reforms had been lacking until recently,” they wrote. “Prime Minister Nehru’s vision of a strong, independent India, with a sound economy generating rapid growth and reduction of the poverty afflicting many among us, is within our grasp if only the economic reforms are sustained and intensified.”

Also read: When Indian economy was liberalised—Manmohan Singh’s 1991 Budget speech

Political contestation

All that PR didn’t work, and neither plan could reach its logical end—politics always got in the way.

“The Mahalanobis model was never allowed to work in practice,” reads an anonymous EPW article published on the cusp of liberalisation, in January 1990. “The influence of the private corporate sector, which got into close working arrangements with foreign capital, proved too strong. The development process on a socially meaningful and broad basis was stymied by the mid-sixties.”

The problem with the Mahalanobis model was that he produced an indicative plan but didn’t produce either the knowledge or the tools to force capitalists to invest in it. The subsequent growth was slow but happened in the right direction—pouring into industry and generating employment. It came to be known as the Hindu Rate of Growth, which averaged about 4 per cent from the 1950s to the 1980s.

The years right after saw wars with China and Pakistan, the death of Nehru, and the rise of a different commitment to a socialist economy with Indira Gandhi’s ascent to power. In both policy and practice, Mahalanobis receded to the background. His name was barely discussed in Parliament beyond the 1960s, save for occasional references to the institute he built and the planning he recommended.

In the 1990s—around the time of the Eighth Five-Year Plan—economists didn’t want to let a crisis go to waste. The challenge was to get the political support to allow the reforms to go through.

“In 1991, we weren’t dreaming of an India. Our backs were against the wall,” said Bhattacharya. “The only ideological belief that all politicians had is that India shouldn’t default and become like a Latin American country.”

It was only in 1991 that the government had the honesty—and courage—to denounce the rigid, structured economic plans that had preceded it, said economist Montek Singh Ahluwalia, who served as the deputy chairman of the erstwhile Planning Commission of India. What compounded the need to change track was the fact that India didn’t have the political stomach to digest an IMF loan.

“The Second Five-Year Plan was conceptualised on an understanding of the economy which was fundamentally wrong,” said Ahluwalia. “The 1991 reforms set the process right. My view is that we weren’t able to do it fast enough. Democracy can only move at a certain pace.”

The Second Five-Year Plan was conceptualised on an understanding of the economy which was fundamentally wrong

—Monetk Singh Ahluwalia

Economists and politicians alike argue that the Indian economy has more or less been on the same path since 1991—just moving at different speeds. “Even Modi hasn’t strayed from this path,“ said Congress politician Jairam Ramesh, who worked with the PMO in 1991.

Also read: ‘Trade, not aid’—Narasimha Rao’s 1991 reforms speech that changed India’s economic landscape

Commemoration—how they are remembered

The planning model was all the rage at the time—in fact, many countries even looked to India as a pioneer of large-scale planning.

American economists were impressed by the scale of Mahalanobis’ ambition: American statistician W Edwards Deming even said, “We in this country, though accustomed to large scale sample surveys, were aghast at Mahalanobis’ plans for the national sample surveys of India. Their complexity and scope seemed beyond the bounds of possibility.”

Known as ‘The Professor,’ Mahalanobis’ five-year plan was mechanically inspired by the Soviet model and sold to Nehru. The Indian Statistical Institute, which he founded, was fifteen years old when India became independent. Nehru and Mahalanobis had met several times before 1947, incidentally discussing planning in 1940 at Anand Bhavan. But it was only after CD Deshmukh became finance minister in 1950 that Mahalanobis stepped into the national spotlight.

Once described as a “physicist by training, statistician by instinct and planner by conviction,” Mahalanobis was the man who shaped India’s approach to planning and policy implementation by emphasising the importance of sample statistical surveys.

However, in a few years, as the dominant mode of economic thinking changed, Mahalanobis would soon be called “Mahabaloney” by some policy wonks in the US. But his legacy was kept alive by the Indian administration’s commitment to the planning model—and set the stage for the radical “course-correction” that was the 1990s. It was also kept alive by the generation of economists who grew under him and shaped the 1990s. Jagdish Bhagwati, for example, was one of the “Professor’s boys.”

“We all drank the Kool-Aid back then,” Bhagwati was known to have said.

The liberalisation reforms of 1991, on the other hand, are remembered as a watershed moment that forever changed India’s economic trajectory.

“India has gone so far down the growth path that there’s no going back,” Bhattacharya said.

Singh’s plan unleashed a trajectory of growth that couldn’t be controlled. In an open market, private capital went where the profits were, while the state pulled back from sectoral investments. Growth became concentrated in sectors favoured by private capital such as services, leaving other areas like manufacturing behind.

The Indian economy switched tracks in 1991, and hasn’t looked back since.

“Now we’re a much more sophisticated, complicated economy and crude interventions can have a very high cost,” said Ahluwalia.

The Mahalanobis plan reflected the thinking at the time on planning and industrialisation, and received broad consensus. It was criticised later, of course. The only person who would have had a problem with it at the time was MK Gandhi

—Jairam Ramesh

The report commissioned by Singh opens with “common misunderstandings” about liberalisation, with Bhagwati and Srinivasan attempting to set the record straight about what was widely conceived at the time as a freefall with no clear outcome. It took direct aim at the Mahalanobis model, questioning the efficiency of public sector enterprises. It was time to stop “treating this sector as a sacred cow, revered and worshipped but often decrepit and destitute,” as they wrote.

The report insisted that liberalisation was not turning back on all that the administration had done until then, though it acknowledged past mistakes: “There is also an understandable feeling that the reforms imply that everything we did earlier, from Prime Minister Nehru’s time, was a failure. In the critical areas where the reforms are concentrated, this is indeed largely true. In some cases, the mistake was not in the original policy but rather in not abandoning it as circumstances changed or became clearer.”

The report carried a preface from Singh, adding his stamp of authenticity as the finance minister.

Also read: PC Mahalanobis: The father of Indian statistics who introduced concept of planned economy

Paths paved by experts

The Second Five-Year Plan was the perfect combination of Mahalanobis’s focus on the role of statistics in planned economic development, Deshmukh’s economic vision, and Nehru’s recognition of both men’s expertise. In 1950, Mahalanobis and Nehru delivered speeches that closely mirrored one another, both asserting that central planning and national statistics were inseparable.

“The Five-Year Plan and the plans that followed were also an outcome of the need for continuity in national planning,” said Jairam Ramesh. “The Mahalanobis plan reflected the thinking at the time on planning and industrialisation, and received broad consensus. It was criticised later, of course. The only person who would have had a problem with it at the time was MK Gandhi.”

Mahalanobis’ ambitious idea to use scientific and statistical economic tools to build an Independent India gripped the administration. It cast its shadow on all forms of institutional planning for decades, in virtually every sector. And it was also what framed the approach of economists like Singh when it came to charting a course.

“The comparison of Mahalanobis and Manmohan Singh is far-fetched—they are in contrast, yes. Mahalanobis wasn’t driving the economy, he simply provided the intellectual framework for it. Dr Singh was very much the architect of the modern Indian economy,” added Ramesh.

Singh, despite having famously written a PhD dissertation in the 1960s that departed from the Mahalanobis model, was still a product of his time. Economists like him and Ahluwalia came of age during this time, working at international organisations like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in the 1970s. When they returned to India and joined the government by the late 1970s and 1980s, economists like them were no longer fashioning policy like Mahalanobis—they were auditing the state.

Ever the insider-outsider, Singh had risen through the economic ranks and had even been deputy chairman of the planning commission—so when it came to prescribing policy, he built on the expertise of the past to address the problems of the present.

The open admission in the 1990s that experts got things wrong in the past was remarkable because the path to economic reform—whether in the 1950s or 1990s—was paved by experts.

The economic debates around the 1950s and the 1990s points to the atmosphere of those times: debate, discussion, and dissent were encouraged. Economists were arguing with each other, and politicians were constantly questioning the finance ministers in Parliament.

Then vs now: The different and the same

Today, there are striking parallels and differences with both economic moments.

“The resonances are so in your face,” said Menon, comparing how both governments emphasised industrial self-reliance. “In fact, Aatmanirbhar Bharat is an idea Nehru would be proud of. If you think of the current BJP government and the Nehru government in the 1950s, their economic policies are not that different—both were dealing with unemployment and manufacturing, and both chose to emphasise economic and industrial self reliance (import substitution then, Make in India now) as the solution. But the way they approach expertise, and the way they make decisions using available data, is crucially different,” he added.

The data infrastructure in India was so strong that between the 1950s and 1980s, India had a better idea of what consumers were spending than even America had, according to economists. But today, there’s a departure when it comes to dealing with data.

In 2017, the BJP government decided for the first time not to release a survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office. Over two hundred academics, including Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton and economist Thomas Piketty, wrote an open letter, asking the government to reconsider its decision. By 2020, even chief economic advisor Arvind Subramaniam was writing in Financial Times that unreliable statistics had caused “damage.”

While there used to be a veneration of expertise, there’s now a scepticism, according to Menon. And this change is compounded by two other diversions from the past: the planning commission being replaced by the NITI Aayog, and a change in the approach to statistical data.

Economists and politicians alike argue that the Indian economy has more or less been on the same path since 1991—just moving at different speeds. Even Modi hasn’t strayed from this path, said Ramesh.

“Earlier, there was a need for politicians to point to expertise to make policy decisions,” said Menon. “In the present moment, this relationship has been severed. Now it’s only politics that is seen as making the decisions.”

(Edited by Prashant)

Irrespective of who’s 35 years it is, and howsoever brilliant these individuals were, in the larger scheme of things it hardly matters. India continues to remain this desperately poor country with limited economic prospects. Sadly nothing seems to change this.

Quality journalism from The Print. Kudos to Vandana Menon for this brilliantly written essay. This is high quality long form journalism, which is in short supply nowadays.

However, I would like to add that Mahalanobis was a statistical pundit whereas Singh was an economist. Quite naturally, Singh understood aspects of the Indian economy which Mahalanobis did not or could not.

But the data collection and processing framework built by Mahalanobis was a pioneering achievement for India. From 1947 till the late 1980s, the breadth and depth of sample surveys along with highly sophisticated data processing methodology put India on a league of it’s own. Most developed countries did not have such high quality data regarding the myriad aspects of economy and society. All developing nations and most developed nations looked up to India when it came to government statistics. This, in turn, resulted in a wealth of information that domain experts could turn to for policy making in their respective fields ranging from public health to education to economy.

This will remain as Prof. Mahalanobis’ legacy and cement his place as a legend of modern India. The Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), built by him, enjoys worldwide renown for it’s research in statistics and mathematics.

Unfortunately, nobody trusts the data put out by the Indian govt anymore. Since the 1990s, coinciding with the post-liberalisation era, Indian statistics has lost it’s pre-eminence. Shoddy data invariably leads to poor planning and policy execution.

Excellent article from Ms. Menon.

This is the kind of journalism we expect from The Print. Please keep it up.

Just a word of caution though. Mr. Mahalanobis must be measured by the yardstick of his times. It’s unfair to put the blame on him for India’s tardy growth rate in the 60s and 70s. He never said or even suggested that his ideas were infallible and should not be modified or tempered as per our needs and changing economic scenarios. He always had an open mind and would readily accept suggestions and advice from domain experts.

Unfortunately, those who succeeded him were an abomination and created the License Raj.