The difficulty experienced by Muthulakshmi brought about a short rift between Chandrammal and Narayanasami Iyer. He stopped visiting Chandrammal’s house, setting the whole town talking. If she had continued her maternal family tradition, Chandrammal would perhaps have composed a musical piece about her man not visiting her anymore, wondering if he was seeing someone else. But Chandrammal had left that life behind. She would stroll every day to Narayanasami’s family home where he lived with his brothers and their families, regally walk to the backyard, pick up some vegetables growing there and saunter back home, her head held high. Tongues wagged of course. ‘When he has stopped going to her house how can she pick vegetables from his garden?’ She was actually doing this to ascertain her right as his partner. This was her husband’s home as far she was concerned. The affection and regard for Chandrammal in Pudukkottai grew multifold after the two reconciled. An amazing act of courage at the time and circumstance she was living in.

Rammohan was just three weeks old when Muthulakshmi travelled to Pudukkottai, on 15 January 1915 to join her husband. He was a delicate baby and had to be wrapped in a shawl and carried by a male nurse who kept awake through the overnight train journey. Pudukkottai was proud to have an FRCS from Edinburgh as their Chief Medical Officer. Such a highly qualified person had not served in the district before. Dr Reddy, in his official capacity and in his private practice, attracted the attention of not just the poor in Pudukkottai, but also quite a few important Chettiars and Zamindars in the district around. Several successful cases made him popular. His fame had spread by word of mouth.

Patients began to arrive in droves to consult him. Though there were quite a few mortalities, many patients made dramatic recoveries which were termed miraculous by their families. There was the instance of a young man gored by the bull he was handling in a Jallikkattu event. His stomach was ruptured and his intestines were visible through the gash in the abdomen. He was wrapped in a wet cloth and carried into the hospital by his friends. Dr Sundaram Reddy attended on him in his usual meticulous way. When the young man recovered, his entire village came to thank him, bearing gifts of agricultural produce in gratitude. Muthulakshmi was no less busy with some extremely difficult pregnancies and deliveries. She also began to attend on urgent cases as there was no alternative medical aid for the women and children in Pudukkottai.

Also read: Male prisoners to male guards — Indian women prisoners’ quest for love in courts, hospitals

The couple had their hands full. Their list in the operation theatre was long and they worked continuously. He travelled as far as 40 miles to attend on patients for which he was rewarded handsomely, gradually paying back the loan he had availed of for his education.

Pudukkottai afforded a luxurious lifestyle as the house was right next to the hospital,with nurses and friends ever eager to help. There was an abundant supply of milk, and grateful patients, rich and poor, brought fruits, vegetables and other goods as gifts for the family. Muthulakshmi breastfed her baby even after her family strongly recommended she should wean it. She believed that a mother must give the natural nourishment of her milk to her baby as long as she could till she is unable to do so. Rammohan’s health picked up. However, for Muthulakshmi there was hardly any rest.

The physical and mental pressure on the couple mounted. Dr Sundaram Reddy developed rheumatism owing to lack of proteins. He fell ill frequently with high fever that would sometimes make him delirious. Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy called for medical help from Madras but none was forthcoming as most of his friends were busy with their practice. Dr Sundaram Reddy’s student arrived to help at the clinic, but all medical decisions had to be taken by Muthulakshmi herself. Rammohan developed whooping cough and suffered a

great deal in the nights, causing his mother great anxiety. She had never seen such suffering. Her sister and she lay on either side of the baby at night with a thermos flask of warm water to wet his throat before he got into a paroxysm of cough. After four weeks a vaidyan who practised indigenous medicine suggested that the baby could be given an ounce of fresh toddy in the morning and evening.

Muthulakshmi was willing to try anything. They noticed some relief, after three days the intensity of the cough gradually reduced. Muthulakshmi writes in her autobiography: ‘Whether it was due to this treatment or due to the natural waning of the virulence of the disease, we do not know. However, we carried the impression it was due to the administration of fresh toddy which contains yeast. When he was a year old, before he got ill with whooping cough, I began to learn Sanskrit letters from one of my old professors in the college who was an M.A. in Sanskrit and very proficient in teaching. I learnt to spell Sanskrit words. I asked for help in reading Sanskrit medical texts.’ This coming from an allopathic doctor shows the open-mindedness she brought to her profession, as much as she did to her personal life.

On recovering from his fevers, Dr Sundaram Reddy resumed his duty, tackling office work,

operating room experiences, the business of medicine, anxiety over anesthesia efficacy and much more, while Muthulakshmi was living the life of an obstetrician. Each day was punctuated with true, unfiltered experiences, funny, joyful, fearful, and tearful, that can

only be found in the life of an ob-gyn surgeon and an anatomy surgeon. The couple never lost sight of their aim to help others find their feet and live a healthy life.

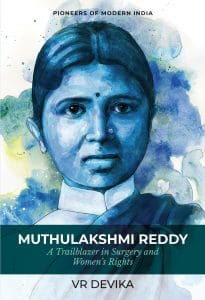

This excerpt from ‘Muthulakshmi Reddy’ by V.R. Devika has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from ‘Muthulakshmi Reddy’ by V.R. Devika has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.