Apart from the above-mentioned regular consumption pattern, occasionally meat of certain other animals and birds was also eaten. This meat was prepared using the same recipes. People would set out to hunt rabbits and ghorpads (monitor lizards) at the onset of monsoon. This tiny army would consist of seven to eight people accompanied by a couple of dogs and was armed with a rabbit trap. If it had just rained, an experienced person in the group would track the rabbit following its footprints. As the footprints became clearer, the group fell silent. The trap would be put up over a slope. Shouting and callings would begin. The frightened rabbit would run towards an open space and get trapped in the net. The hunters would keep a cautious distance from the rabbit: it is believed that the caught rabbit blows air into its hunter’s eyes, making the latter’s eyesight turn weaker day by day. Rabbit meat is darkish red and delicate. If it was a female, one would invariably find a foetus inside her. It was not a surprise. Rabbits are ready for mating immediately after giving birth to the previous litter. A cycle of seven to eight babies every two to three months is common.

On such hunting trips, sometimes sun-bathing monitor lizards were found on the hilltops. Rainwater seepages in their burrows forced them to come out to rest and keep warm. They would run into the burrows immediately and the hunters would dig them out. One was very careful while catching them as it was believed that if the monitor lizard hit someone with the tail, the person ceases to be a ‘man’. Effeminate men would be taunted with remarks like, ‘It seems this guy has been hit by a ghorpad’s tail!’ The monitor lizard’s meat tastes like chicken. There is layer of green oil on the curry when it’s cooked. The skinning of a monitor lizard was also done by an expert. Its hide was in great demand by makers of musical instruments. This was because the skin stayed tight and did not catch fungus easily. The sound of those instruments would be organically set on a higher scale. Monitor lizard’s skin is easy to recognize. It is marked with small dark rectangles and squares.

Apart from this, occasionally eggs of pigeons, quails, ducks and peahens would be eaten if found. Similarly, doves, spotted doves (with a black necklace-like design around their necks), pigeons, ducks, waterfowls, migratory birds, hornbills and large migratory birds that primarily resided in safflower farms, etc., were also hunted.

Since this region is quite far from the sea, saltwater fish are not used in their diet. But the tradition of drying saltwater fish and selling them in faraway places is quite old. Their weekly markets are engulfed with the peculiar smell of dried fish. And these people love the dried variety of shrimps, small prawns, peeled large prawns and Bombay duck. They would fry all varieties of dried prawns by adding onion, masur dal (red lentils), turmeric, salt, coriander and either red chillies, green chilli paste or yesur. Sometimes they used to cut the dried Bombay duck into pieces and roast them, and make a thick gravy like that of the gravy of chaanya.

Haade or hadka (bones)

Not a scrap of an animal was wasted. If it could not be eaten or used in the community, it was sold, as were the bones of scavenged animals. Occasionally buyers of animal bones would visit settlements of these castes. There were discussions and speculation amongst these castes that these buyers made saras (a glue used in book binding) and cups and saucers from these bones. When the glue made from bones was cooked with water for use, it emitted a similar but much stronger odour than that of horns burning.

Shingat (horn of a dead animal)

Shingat is the horn of a dead cow, bullock or buffalo. It had its uses, too. If a snake went into someone’s house, they would burn a shingat. This was a ‘remedy from grandmother’s purse’ (a phrase used for all undocumented tricks of wisdom and medicinal know-how passed on down the generations, usually through old women). Burning a horn would emit a strong and pungent odour which was similar to burning hair. (Biologically, horns are composed of hair.) Since it was believed that snakes were ‘Brahmin’, they would flee from this smell. This peculiar smell emitted from a particular house told the neighbours about the presence of a snake in that house.

The prosperous and well-off upper-caste farmers had various ways to store their surplus grains, such as kanagi (bins), balad (a dark room) and pev (underground storage). Pevs were so huge that several quintals of grain could be stored in it. When the grains stored everywhere else were finished, they would use what was stored in the pevs as a last resort. ‘Pev futaney’ (the store has burst open) is a famous phrase in Marathi which means sudden abundance. After opening the pev, a lighted lantern was kept in it. Only if it stayed lit did the servants descend into the pev. If the lantern snuffed out, it meant that there was not enough oxygen and they would die if they stepped in.

When compared to this abundance, how much would be the surplus harvest for these two castes? Certainly not more than what would fit into the hollow horn of a dead animal. If someone had a harvest in their small farms, when asked about it they would refer to it as ‘shingatat pev’. That is, ‘Our harvest is so little that it fits into a shingat—but that’s like a pev for us.’

Phrases such as ‘Deed dana an Mang/Mahar utana’ were popular too, which meant the man belonging to these castes would lie down flat if you offered him one-and-a-half grains of food.

There was pain underlying their sayings, but the speaker and listener would both break into laughter. Although the Mangs and Mahars lived in extreme poverty, they were also adept at finding humour in their own situation.

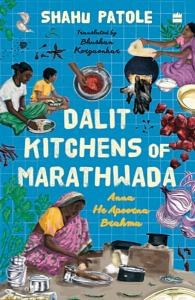

This excerpt from Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada by Shahu Patole has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada by Shahu Patole has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.