Next time you encounter a Lakmé shop selling ‘absolute perfect radiance skin-brightening crème’ and other such products, remember Goddess Lakshmi as the inspiration behind the first indigenous cosmetic brand name in independent India. Lakshmi and Lakmé are inseparable. After Independence in 1947, when Indian industry was struggling to establish a stable economy, the prime minister and his cabinet realized that Indian women were spending precious foreign exchange on buying expensive, imported beauty-care items. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru approached industrialist Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata for a solution.* The seeds were sown for an Indian brand of cosmetics that could woo women away from ‘foreign goods’ by promising the same results and at a much lower price.

While the oils and potions were being developed in association with a French team, the quest for a name began. The initial suggestion of ‘Lakshmi Beauty Products’ wasn’t sassy enough—and French collaborators Robert Piguet and Renoir came up brilliantly with ‘Lakmé’ which was a French version of the goddess’s name. The French link endured steadily as Simone Tata, the wife of Naval H. Tata, joined Lakmé as its managing director in 1961 and rose to become the chairperson in 1982.

Today, Lakmé products are exported to more than seventy countries worldwide, and Goddess Lakshmi must surely be amused because the colonialist vision of India has been replaced with admiration for Indian modernity. The name ‘Lakmé’ to Indian women in the 1950s denoted a conjoining of East and West— exotic yet local, seductive yet modest. When the cosmetic brand Lakmé launched in India in 1952, its tagline was: ‘If colour be to beauty what music is to mood, play on.’ Shyamoli Verma, India’s first supermodel, endorsed the brand by displaying traditional Indian clothes and classical instruments with a gorgeous makeover of Indian skin, lips and eyes. Goddess Lakshmi must have smiled with indulgence as her French protégée Lakmé continued on a steady run of commercial success.

Linking Lakshmi to Lakmé was no arbitrary spin. According to historical sources, ‘Lakmé was an opera written by Léo Delibes, a French Romantic composer, set to a French libretto by Edmond Gondinet and Philippe Gille, and was first performed in 1883 at the Opéra-Comique in Paris.’* In the story, Lakmé is the daughter of a Brahmin priest who falls in love with Gerald, an officer in the British Army in India. While he wishes to rescue her from the authoritarianism of her father, he is also committed to his own country and career. The opera, which was popular then, and surprisingly continues to be performed occasionally—such as in 2012 in Australia—is replete with mysterious rituals and stage artefacts, and the singers are dressed in excessive jewels and elaborate headdresses. Clearly, the storyline and the staging details demonstrate allegiance to the popular orientalism of the 1880s where the ‘gaze’ was trained ambiguously at the marvels of the East. It suggests ‘the White man’s burden’ on one hand and gestures towards an attractive nativism on the other.

Much has changed with the evolution of independent India but the brand value of Goddess Lakshmi has endured. The Government of India’s welfare schemes for the girl child have often used the lure of Lakshmi’s name to convince parents from deprived backgrounds to register for the benefits. Largely a consequence of census figures that repeatedly showed an adverse sex ratio, indicating that girls were subjected to foeticide and possibly infanticide in many parts of the country, these schemes started appearing in 2008 and have continued till now in some form or other.

The Dhanalakshmi Scheme, launched on 3 March 2008 by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, was a ‘conditional cash transfer’ for the girl child. The aim of the scheme was to value the life of a girl child and not treat her as a liability. It attempted to stop child marriage, encourage education and cover medical expenses. Parents were offered an attractive insurance for keeping their daughters safe.* In terms of popular understanding, Lakshmi is the goddess of wealth. By linking the birth of a girl child to this aspiration for prosperity, the public rhetoric hoped to convince parents that the child brought material assets with her to ensure her nurture, and that her well-being would help the family too. The basis was monetary as the cash transfers were linked to signposts such as birth registration, immunization, school enrolment and attaining the age of eighteen. A substantial insurance of Rs 1 lakh would be granted at that point.* Since monitoring such a scheme was an astounding task, reports showed a large number of roadblocks mentioned by implementing agencies as well as potential beneficiaries.

The original Dhanalakshmi Scheme is no longer available and has been recast in new programmes such as Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, started on 22 January 2015. From the point of view of mythological interpretation, one is glad to see the shift away from monetary incentives in the name of Lakshmi to a more holistic view of empowering the girl child through education. Moreover, the patriarchal norm of marriage as the ultimate goal by which to judge the survival and wellness of a girl child ought to be cast away.

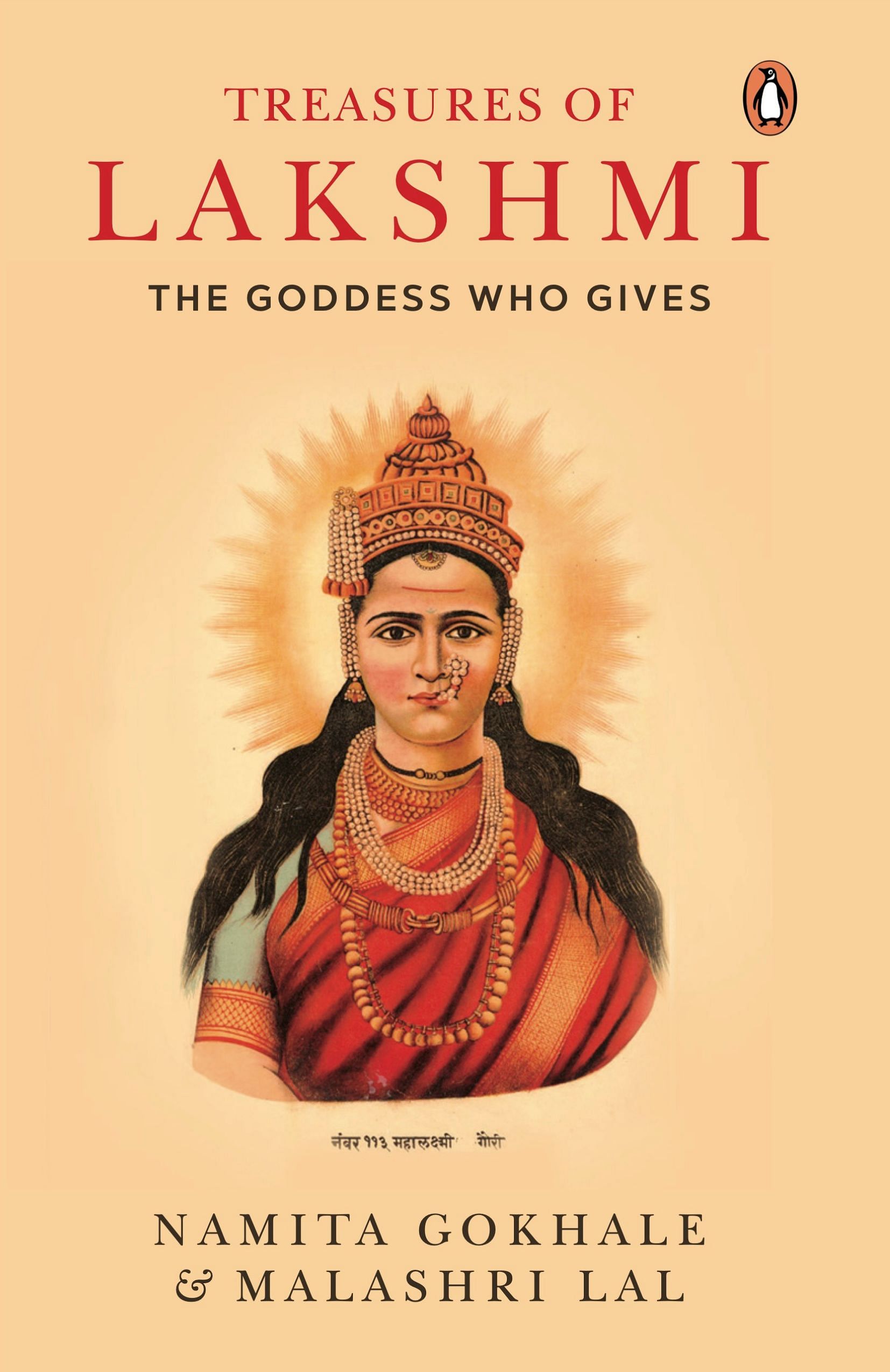

This essay by Malashri Lal, is an excerpt from Treasures of Lakshmi: The Goddess Who Gives edited by Namita Gokhale and Malashri Lal has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This essay by Malashri Lal, is an excerpt from Treasures of Lakshmi: The Goddess Who Gives edited by Namita Gokhale and Malashri Lal has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.