Cholera also started out in the bodies of animals. The creatures that harbored cholera live in the sea. They’re a kind of tiny crustacean called copepods. They’re about a millimeter long, with teardrop-shaped bodies and a single bright-red eye. Since they can’t swim, they’re considered a kind of zooplankton, drifting in the water and delaying gravity’s pull to the depths with long antennae splayed outward like wings on a glider plane. Though they’re not talked about much, they’re actually the most abundant multicellular creatures on Earth. A single sea cucumber might be covered with over two thousand copepods, a single hand-size starfish with hundreds. In some places, the copepods are so thick that the water turns opaque, and in a single season each one may produce nearly 4.5 billion offspring.

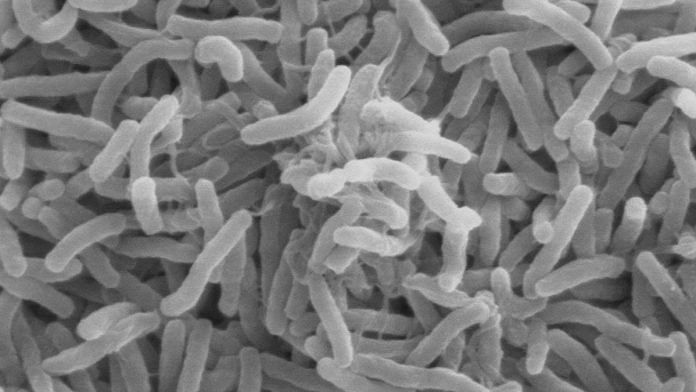

Vibrio cholerae are their microbial partners. V. cholerae is a microscopic, comma-shaped species of bacteria from the genus Vibrio. Although V. cholerae can live on its own, free-floating in the water, it collects most lushly in and on copepods, sticking to copepods’ egg sacs and lining the interior of their guts. Vibrio bacteria performed a valuable ecological function there. Like other crustaceans, copepods encase themselves in crusty exteriors made of a polymer called chitin (pronounced “kite-in”). Several times during their lifetimes, they shed their outgrown skins like snakes, discarding 100 billion tons of carapaces annually. Vibrio bacteria feed on this abundance of chitin, collectively recycling 90 percent of the ocean’s excess chitin. Were it not for them, copepods’ mountain of exoskeletons would starve the ocean of carbon and nitrogen.

Vibrio bacteria and copepods proliferated in warm, brackish coastal waters, where fresh and salty waters met, such as in the Sundarbans, an expansive wetlands at the mouth of the world’s largest bay, the Bay of Bengal. This was a netherworld of land and sea long hostile to human penetration. Every day, the Bay of Bengal’s salty tides rushed over the Sundarbans’ low-lying mangrove forests and mudflats, pushing seawater as far as five hundred miles inland, creating temporary islands of high ground, called chars, that daily rose and vanished with the tides. Cyclones, poisonous snakes, crocodiles, Javan rhinoceros, wild buffalo, and even Bengal tigers stalked the swamps. The Mughal emperors who ruled the Indian subcontinent up until the seventeenth century prudently left the Sundarbans alone. Nineteenth-century commentators called it “a sort of drowned land, covered with jungle, smitten by malaria, and infested by wild beasts,” and possessed of an “evil fertility.”

But then, in the 1760s, the East India Company took over Bengal and with it the Sundarbans. English settlers, tiger hunters, and colonists streamed into the wetlands. They recruited thousands of locals to chop down the mangroves, build embankments, and plant rice. Within fifty years, nearly eight hundred square miles of Sundarbans forests had been razed. Over the course of the 1800s, human habitations would sprawl over 90 percent of the once untouched, impenetrable, and copepod-rich Sundarbans.

Also read: Why humans have themselves to blame for the coronavirus pandemic

Contact between human and vibrio-infested copepod had probably never been quite so intense as in these newly conquered tropical wetlands. Sundarbans farmers and fishermen lived in a world semi-submerged in the half-salty water in which vibrio bacteria thrived. It wouldn’t have been particularly difficult for the vibrio to penetrate the human body. A fisherman who splashed his face with water by the side of a boat, say, or a villager drinking from a well corroded with a few ounces of flood-waters, could easily ingest a few invisible copepods. Each one might be infested with as many as seven thousand vibrios.

This intimate contact allowed Vibrio cholerae to “spill over” or “jump” into our bodies. The bacteria wouldn’t have found a particularly welcoming reception there, at first. Human defenses are designed to repel such intrusions, from the acid environs of our stomachs, which neutralize most bacteria, and the competitive wrath of the microbes that inhabit our gut to the constantly patrolling cells of the immune system. But in time, V. cholerae adapted to the human bodies to which it was repeatedly exposed. It acquired, for example, a long, hairlike filament at its tail that improved its ability to bond to other vibrio cells. Endowed with the filament, the vibrio could form tough microcolonies that could stick to the lining of the human gut like scum on a shower curtain.

Vibrio cholerae became what’s known as a zoonosis, from the Greek zoon for “animal” and nosos for “disease.” It was an animal microbe that could infect humans. But V. cholerae wasn’t a pandemic killer yet.

This excerpt from Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, From Cholera To Coronaviruses And Beyond by Sonia Shah has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, From Cholera To Coronaviruses And Beyond by Sonia Shah has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

What has this scientific topic got to do with the roughly 150 year old rule of North and Eastern Indian sub-continent by the Mongols (Mughal in Persian) ? In that vein every empire which ruled over Bengal before the British – such as the Bengal Sultanate, Pala Empire etc. can be credited with ‘not destroying’ the Sundarbans. Please stay away from such clickbait headlines to an actually interesting scientific article. Thank you.

Glory to the British and their Shenanigans!!!! I guess the European attitudes to venture and tame the wild and put it to their own personal use is incredible. So they destroyed the sunderbans as well… Add to the list…