Gandhiji and Kasturba came to Madras in 1925, en route to Thiruvananthapuram. This was when the Vaikom Satyagraha, in connection with the temple entry, was going on. They stayed at my home for three days. On their previous visit, we had held a reception for them in the garden. This time, we invited Gandhiji in, seated him on a mattress of khaddar and literally worshipped him. Why this change? Well, Gandhiji too had transformed. Then he was a civil rights activist owing to his role in the South African civil rights movement. Now he was a role model—a man who had sacrificed his life for the sake of the country!

All through the day, people came to see him. One devotee came with his six-year-old daughter. Gandhiji placed her on his lap and began conversing with her. He saw her gold bangles and asked, ‘Child, will you give them to me?’ She immediately said yes and then looked at her father. Everyone was watching in stunned silence. ‘Please give Gandhi Thaatha your bangles,’ said the father. Gandhiji was a master at begging for what he wanted. He immediately began to slip the bangles off the girl’s hands. But it was not so easy. ‘Get a pair of pliers,’ he declared! I, who was watching this with other women, was somewhat annoyed with the Mahatma. I quickly went indoors and placed the pearl necklace I was wearing in the safe.

On one of the three days of their stay, we organized a special meeting for women, to be presided over by Kasturba at Vasantha Bungalow in Thiruvallikeni. She gave a brief speech in Hindi. At her request, all the women led by Kothainayaki Ammal donated their jewellery to fund the cause. This was the first time the women of Madras donated their jewellery for a noble cause. From then onwards, Gandhiji spoke highly of South Indian women and commended their willingness to sacrifice. I must add here that it was Gandhiji who reduced to a great extent the craze Indian women had for jewellery.

During his stay with us, Gandhiji was reading Katherine Mayo’s book Mother India. The author, an American, had written very derogatively and in a biased manner about Indian women. She had described them as brainless, uneducated, bound to the kitchen, and unaware of the outside world. She had also written that Indians were not qualified to become independent. The Mahatma described the book as a sanitary inspector’s report in an article in Young India. He asked me if I had read it. When I said no, he gave it to me and asked me to read it and give my opinion on it by nightfall. When he asked me my views the next day, I said that though it was largely nonsense, there were some home truths in it. He said it was his view that educated women like me ought to work to eradicate the faults highlighted in the work. Mayo’s book and the Mahatma’s opinion of it gave me a new goal in life—that of social service.

Gandhiji observed silence on Mondays, and on one of those evenings, he was seated on the first floor, engaged in writing articles for Young India. Some of those present asked me to play the veena. While I was doing so, a note came from the Mahatma. I was stunned to read what he had written: ‘You may think being immersed in work, I am not paying attention to your performance. But I am listening to it even as I write.’ I was overcome by embarrassment.

Mahadev Desai, who was nearby, asked me if I understood the lyrics and import of the songs I played. How was I to tell him that I did not know anything of the Tyagaraja and Dikshitar compositions I performed!

The three days the Mahatma stayed with us went by in a flash. All my time was spent observing Gandhiji: what he did, noting where he was going, attending to his wants, and watching how he spoke and laughed. When he left, I was completely rudderless. It appeared as though life had come to a halt. I wandered around the house. I treasured every object he had used and considered them articles of worship. A great joy permeated by sorrow filled my being.

That year, in the month of April, my brother’s wife gave birth to a daughter. According to my father’s wishes, she was named Vasanthi, after C.R. Das’s wife. My son continued to be plagued by illnesses. Western medical practice recommended feeding the child every three hours but Indian nurses fed him whenever he cried. Child rearing is a difficult art that every woman ought to be trained in.

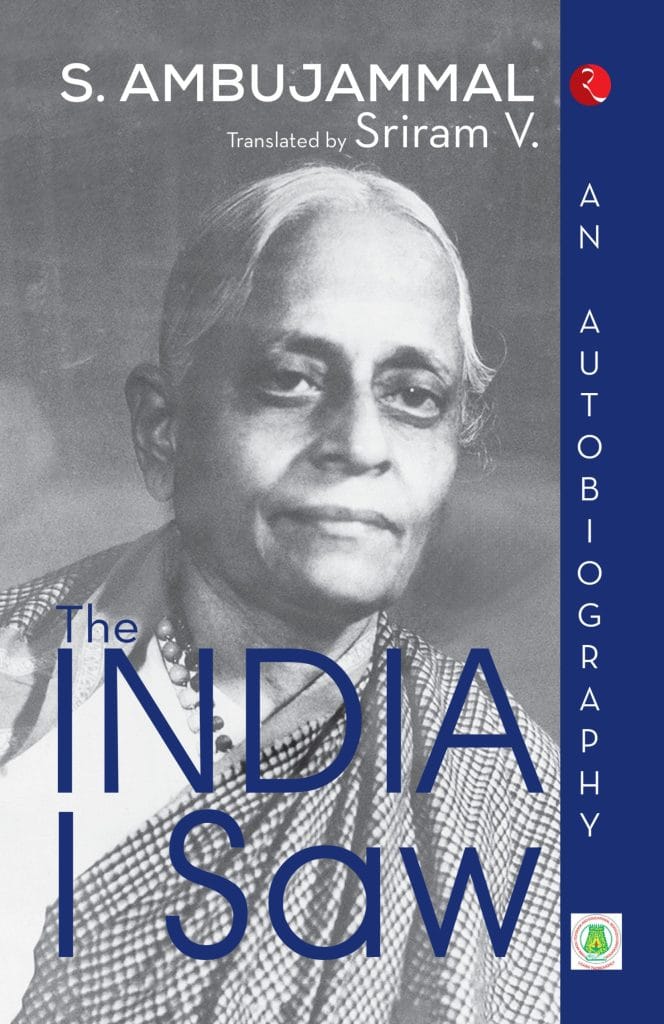

This excerpt from The India I Saw: An Autobiography by S Ambujammal and translated by Sriram V has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from The India I Saw: An Autobiography by S Ambujammal and translated by Sriram V has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.