Please take it seriously when I say that my whole heart is with you in the great work you have started. I wish I were young enough to be able to join you and perform the meanest work that can be done in your place, thus getting rid of the filmy web of respectability that shuts me off from intimate contact with Mother Dust. It is something unclean like prudery itself to have a sweeper to serve that deity who is in charge of the primal cradle of life.

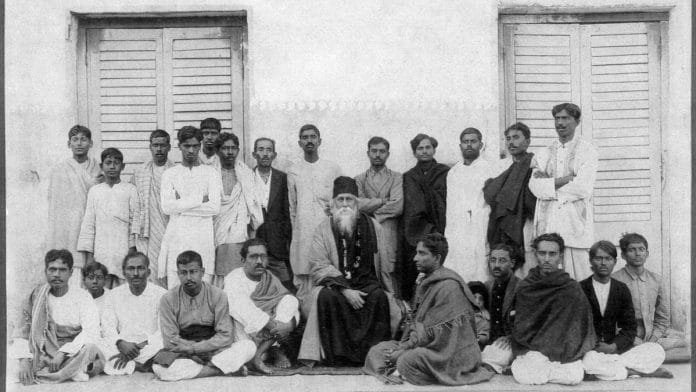

Rabindranath sent the above note to the Sriniketan pioneer L.K. Elmhirst on 31 March 1922, when he learned that the first batch of Surul students had dug trenches in their own backgardens to dump the night soil to help in the improvement of agriculture. Rabindranath very eagerly looked forward to the day when his village work would benefit from the contributions of modern science.

In as early as 1906, he sponsored three young men from Santiniketan to study agriculture and dairy farming at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, in the USA. They were his son Rathi, his son-in-law Nagendranath Ganguli (1889–1958, married to Rabindranath’s youngest daughter Mira Devi), and his friend Srishchandra Majumdar’s son, Santosh Chandra Majumdar (1886–1926, student of the Santiniketan school, and afterwards, teacher too). The plan was that at the end of their higher studies in agricultural sciences, they would bring their newly acquired knowledge to the work of rural reconstruction in India.

Rabindranath felt sure from his observation of other agricultural countries that the economic salvation of the village lay in the application of expertise. In 1909, all the three graduates from the University of Illinois returned with their state-of-the-art training in agriculture and animal husbandry and began to introduce scientific methods to the Sriniketan work. Their experiments were carried out jointly with the villagers.

To take the work forward, Rabindranath bought 20 bighas of land in 1912, along with a house that stood on that plot of land just outside the village called Surul, within two miles west of Santiniketan, where the Sriniketan Institute was to be located. The house that stood on the land was commonly known as ‘Cheap Kuthi’. It belonged to the East India Company’s Commercial Resident for the District of Birbhum, John Cheap, who lived in it from 1787 to 1828. His job was to indent the local supply of cotton and silk fabrics on the Company’s account with an annual investment quota of 45,000 to 65,000 in Pounds Sterling. Silk and cotton fabrics comprised the major portion of the East India Company’s advances. The weavers used to work on a system of ‘advances’, all of which was handled by the Company’s Commercial Resident.

As Commercial Resident, the punctual supply of the Company’s requirements was the main job. For that, good cooperation was needed from the local agents. Mr Cheap found Surul and its neighbourhood not only rich in raw materials, but he also found a friend and ally in an influential landlord cum businessman of Surul, Sri Srinivas Sarkar. It was from the Sarkars that John Cheap obtained a vast tract of land, on which he built his palatial house surrounded by a garden and an orchard. It was an impressively large house, but fallen into ruin by the time Rabindranath bought the property. The fact that John Cheap was posted at the place by the East India Company was proof of the earlier prosperity of the region.

John Cheap encouraged spinning and weaving in the villages around. He collected his produce, as well as the other goods for sale, through a network of huge clearing stations. It is believed that his enterprise brought the whole area to a level of prosperity, which was seen in a sprouting of ‘pukka’ buildings, houses, and temples. Machine-spun cloth with identical patterns, copied from Cheap’s exported goods, began to reach the Port of Calcutta at cut rates. But the inevitable outcome was that Birbhum’s hand-woven cloths were thrown out of the market. As a result, the villages were ultimately reduced to poverty and infested with the diseases of cholera and malaria. This was also the time when the district was getting its first railway line. The massive digging undertaken by the East India Railways in laying the Bolpur Line had an adverse impact on the environment and the people’s health.

Also read: ‘History of Sriniketan’: Book throws light on Rabindranath Tagore’s work for rural reconstruction

For the first few years of the Sriniketan work, nothing substantial could be done with that plot of land except to clear the jungles surrounding the area of ‘Cheap Kuthi’ and to meet the villagers. A scheme was also started to make the Surul farm into a model for the benefit of the cultivators living in the surrounding villages. This holistic task was led by Rathi Babu and Nagendranath Ganguli, who, armed as it were, with their study and training at the University of Illinois were ready to make an impact on rural reconstruction. But nothing came of those early attempts to start the work in earnest, because all the workers came down with malaria. That is how the initial 10 years were spent like a roller coaster with starting the work and stopping it at intervals.

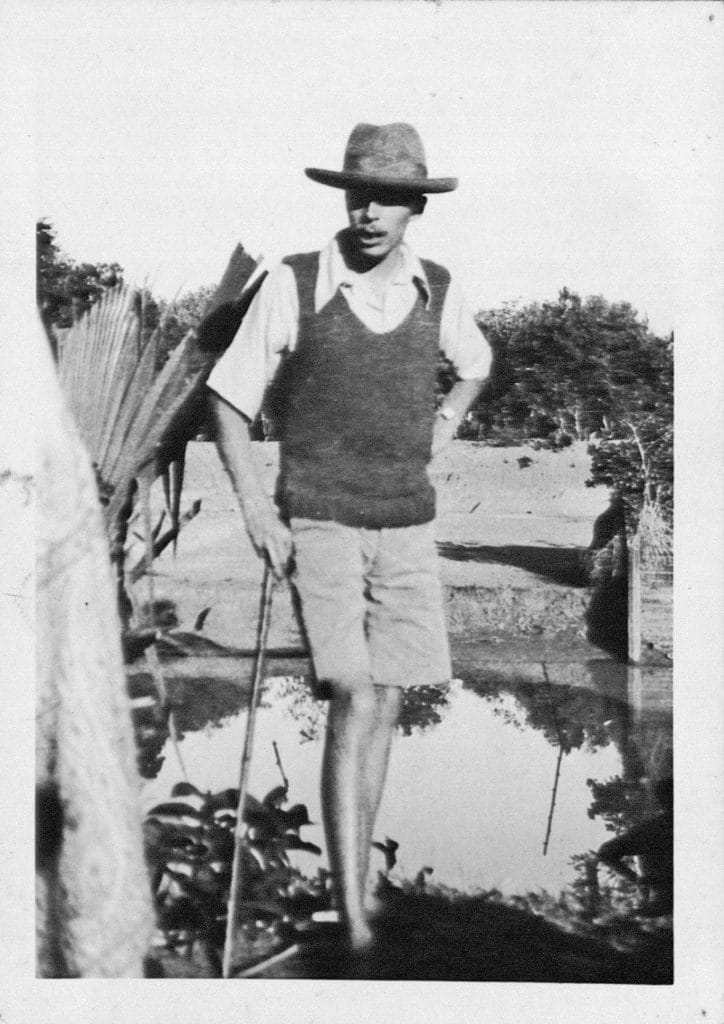

In 1921, Rabindranath travelled widely to inform the larger humanity about his Visva-Bharati International University at Santiniketan, a ‘place’ for the world to meet as in a single ‘nest’. When he was in the USA, he arranged to meet a young Englishman who was then a student of agriculture at Cornell University. This was L.K. Elmhirst (1893–1974, agricultural economist, led the Sriniketan work during 1922–24, and later gave it his lifelong support). Rabindranath had been told about Elmhirst by another Englishman, Sam Higginbottom (1874–1958), who founded the Nainital Agricultural Institute, where Elmhirst had worked for some months as a wartime volunteer in 1917–18. Rabindranath appealed to Elmhirst to come over and start the Surul Farm.

About their meeting Elmhirst wrote:

I remember well the morning in the spring of 1921 when a telegram reached me at Ithaca, from Tagore, which read ‘Come and see me in New York. I made a hurried journey to New York, and shall never forget the friendly welcome I received. ‘I have’, Tagore said to me, ‘an institution of learning and the arts at Santiniketan which is mainly academic. It is surrounded by villages, some Hindu, some Muslim, some Santal, but all are decaying; all had an ancient culture, but today they appear sick. Will you come and help me to find out why? Would you be prepared to go and live in a village? Would you like to consider it? Then how about sailing back with me tomorrow?’

‘But’, said I, ‘if I am really to be of any use to you, I must finish my course at Cornell’.

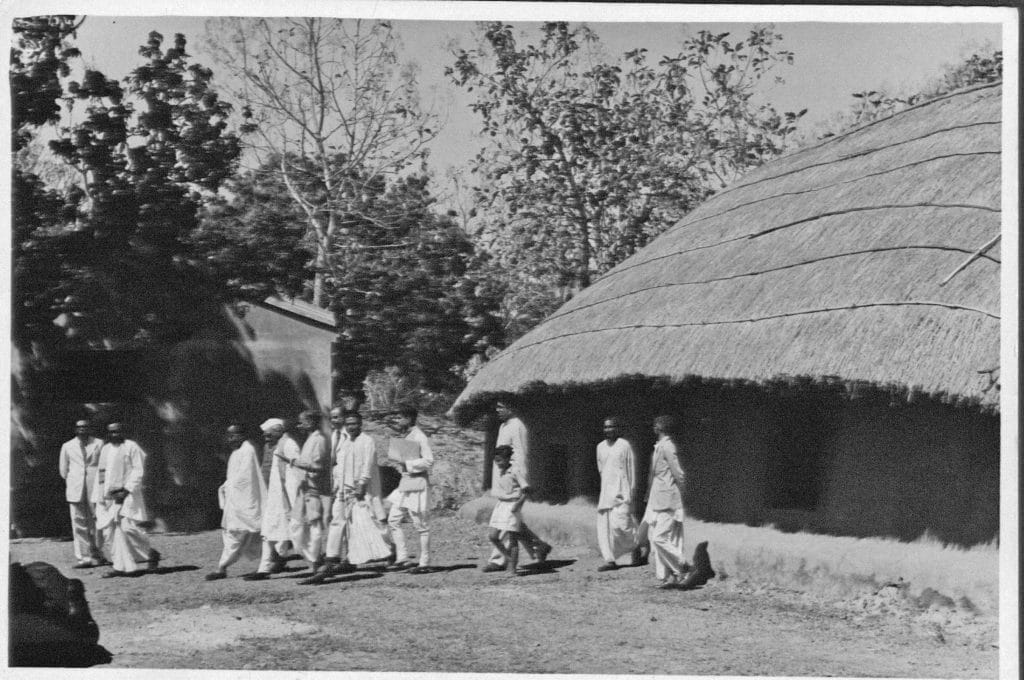

Elmhirst came to work for Sriniketan after completing his course of studies at Cornell. He came to Santiniketan at the end of 1921 and started the rural work in 1922, by moving to Surul with a team of two teachers and 10 senior students from the Santiniketan school. In the team were Rathi Babu, Santosh Majumdar, and Kalimohan Ghose, whom Elmhirst referred to as his ‘three closest collaborators’. Another resource person who joined them soon after was Miss Gretchen Green from the USA, a paramedical nurse, who was asked to set up the Village Health Centre and Clinic at Surul.

It was not easy at first for the Santiniketan-Sriniketan team to start their work as there was an ongoing political movement at the time. Gandhi’s Non-cooperation Movement had touched many hearts, even in Santiniketan. The political ferment also affected the team’s relationship with the villagers to some extent. Elmhirst wrote in his diary how Rabindranath used to discuss their local problems and experiences regularly and consulted, in particular, with Kalimohan Ghose, as he was the Sriniketan contact person with the local villagers. Moreover, the villagers trusted Kalimohan Ghose.

Initially, the team took up reconstruction work in the three designated villages in Surul’s neighbourhood. The records in Elmhirst’s diary refer to the desperate struggle they had in making the initial contacts, at first, with the Muslim villages, and later, also with the Hindu villages. Again, as Elmhirst wrote in his diaries, Rabindranath learned about it all from Kalimohan and gave his encouragement to keep the work going and reiterated his support for it.

Also read: Students expelled, teachers under fire, rank tumbles — turmoil in 100th year of Visva-Bharati

After getting the work started, Elmhirst could stay for only two years, from 1922 to 1924. He had to return to England to start his own educational institution, Dartington Hall in Devonshire, though he remained connected with the Sriniketan work throughout his life. His correspondence with Rathi Babu bears out how closely he followed all matters of Sriniketan, even criticized some of it in his assessment. Rathi Babu sought Elmhirst’s advice earnestly, and a number of the leading village workers also stayed in touch with him. Elmhirst himself returned to Sriniketan on short visits every couple of years. The lady he married, Dorothy Whitney Straight (1887–1958), endowed an annual grant of Rs 32,000 for Sriniketan, which was of foundational help to the work over the years. That is how Sriniketan’s ‘permanence’ was ensured. Dorothy Whitney Straight was the daughter of the American financier, William Whitney, and the widow of the distinguished diplomat Willard Straight. Rabindranath dedicated his book of essays, Pioneer in Education, to Dorothy with the following words, ‘To Dorothy Whitney Straight who made Sriniketan possible’.

When the Sriniketan work was being conceived, Rabindranath insisted on an all-rounded approach that would take account of the villager’s life in all aspects. He also asserted his confidence in the cooperation of the young people in bringing about the reforms and in gradually taking along their elders with them to that end. That is why he was attracted to the Scout Movement founded by Lieutenant General Robert Baden-Powell (1857–1941, founder of the worldwide Scout Movement), and decided to tie up the Sriniketan experiment with the Scout Movement. Rathi Babu arranged for two boys from the Santiniketan school to join a training course for Scout leaders in the Central Provinces.

Among the other aspects of the Sriniketan experiment, Rabindranath encouraged the collaboration of scientists, economists, sociologists, and technicians with the work. He encouraged one and all to stand by the villagers in their struggle against poverty and oppression. He was also cautious that the team did not impose too much ‘statistics’ or technicalities on the villagers in bringing about the changes. He wrote to Elmhirst, ‘All the time when Sriniketan has been struggling to grow into a form, I was intently wishing that it should not only have a shape, but also light, so that it might transcend its immediate limits of time, space and special purpose.’

This excerpt from ‘History of Sriniketan: Rabindranath Tagore’s Pioneering Work in Rural Reconstruction’ by Uma Das Gupta has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from ‘History of Sriniketan: Rabindranath Tagore’s Pioneering Work in Rural Reconstruction’ by Uma Das Gupta has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.