Imran Khan is one of the greatest captains and players the game has seen. Why I hold this view hardly needs qualification. His record speaks for itself, and, if at all further validation is necessary, it comes from the experiences of those who played with or against him.

The first time I saw Imran play was on TV, when India toured Pakistan in 1978. He was then making a mark as one of the best all-rounders in cricket after a rather slow start to his career. His performances in Australia in the 1976 series and in Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket had helped his reputation soar. Against India Imran was quick, but without having quite the same control that would make him so formidable a couple of years later. His big hitting, especially in the exciting run chase in the third Test at Karachi, won him more renown in India then.

When Pakistan came to India the next season, I made sure to get a place in the North Stand at Wankhede Stadium. Theirs was a star-studded team, in which Imran was the biggest attention grabber – for cricketing reasons and otherwise. Imran didn’t have a great match though, injuring himself and not bowling in the second innings. He struggled with his fitness through the series, which affected his team’s chances. Pakistan lost the Bombay Test and subsequently the series against a determined Indian side.

But how brilliantly he made up for this disappointment when we toured Pakistan in 1982-83! By now, I was part of the Indian team and got to experience Imran’s fantastic skills – with ball and bat – from just 22 yards away.

Also Read: Shastri practical, Hesson analytical: Details of meeting that picked Team India’s head coach

In his prime, in the early and mid-1980s, I’d unhesitatingly say he was the best fast bowler in the world. He had both pace and the ability to swing the ball lethally late. But for the injury he sustained in the series against us that prevented him from bowling for almost two years thereafter, he would easily have picked up 150–160 sticks more.

Imran’s strength was his remarkable control over swing and reverse swing. The steeply curving late inswingers, or ‘indippers’ as they were called then, made life hellish for batsmen. We did not have much understanding of reverse swing then, and Imran had us bamboozled. His accuracy meant there was no respite. He could vary the length of the delivery depending on pitches, conditions and countries he was playing in. Even the best batsmen found it difficult to cope with the late movement that would send the ball darting in or away at the last second.

In the 1982-83 series, Imran demolished us – though we had a strong and experienced batting line-up – on pitches that did not really support fast bowling. Opening the innings in the sixth Test at Karachi in the series, I got to see Imran exhibit his full repertoire of marvellous skills. I scored my first Test century in that match, but there wasn’t a single delivery when I was not under threat when he was bowling. Although Pakistan had already won the series and Imran was carrying a painful calf, his desire for success was unrelenting.

Over the next six or seven years, India and Pakistan engaged in several contests – Tests and ODIs – and Imran easily towered over all players in his side. This might be only perception, but he also seemed to be at his most aggressive against India. I realized what a fierce competitor he could be through a couple of exchanges in the middle.

Also Read: Ravi ‘Bhai’ Shastri back to serve Kohli & boys. Time will tell how far this bonhomie goes

In 1987, when I was leading the Under-25 team against Pakistan, Imran arrived late to the stadium for the match. He apologized, saying he was stuck in traffic. Fair enough, but he wanted to start bowling straight away, which I wasn’t agreeable to as this was against the rules. Sensing the umpires were vacillating, I told them to mind their own business and go by the book. Imran’s message to Wasim Akram and the other bowlers in that game was to bounce the shit out of me.

Sometime later, when we were playing Pakistan in Sharjah, I suddenly got stomach cramps while batting and requested for a runner. Imran refused. We were 100 something for no loss then. I fell in a couple of deliveries. From a solid start, wickets started tumbling and we went on to lose the game chasing a modest 240-odd.

Imran had not forgotten what I’d done to him earlier and paid back in kind. But while he played it real hard, he left the contest on the field. Off it, he was friendly but reserved, keeping pretty much to himself. Many thought him to be aloof and snobbish; I think he was reserved, and not one to socialize readily.

Among the four great all-rounders of that era, Imran was the best batsman, technically and temperamentally. He could bat at any number and, more importantly, according to what the situation demanded. His long stint in county cricket and experience in the World Series Cricket had made him value professionalism over pointless bravado. Wasim Akram told me about the countless lectures, some of them very stern, he and other young players got from Imran if they had thrown their wicket away or bowled poorly even though Pakistan had won.

Winning the World Cup at the fag end of his career, when he was a quarter of the bowler he used to be, was nothing short of extraordinary. It was sheer self-belief that goaded Imran to chase this honour. He led from the front, batting up the order in the semi-final and final to control the innings.

The pride that he took in playing for Pakistan not only boosted his own performances, but also inspired several generations of young cricketers in his country to excel. He was a demanding captain, but also made heroes of others, his greatest quality as a leader. He was autocratic but also inspirational, and determined to leave behind a legacy.

Also Read: Virat Kohli’s ‘camaraderie’ with Ravi Shastri makes him India’s most powerful captain yet

I admired his poise and calm demeanour on the field. He never appeared ruffled, however grave the situation; never gave opponents an inkling that he was under pressure. His decision-making was swift, and, if it didn’t work, he moved on, trying the next gambit. He was a man of action, not a brooder.

Also of unwavering resolve. The cancer hospital Imran built in memory of his mother is testimony to this. It took years to raise funds and see the project through, but he never let up.

Soon after retiring, he joined politics, making little headway in the first few years. When I asked Wasim Akram on one of our commentary assignments whether Imran had made a mistake by jumping into politics, he replied, ‘If Khan sa’ab has decided on something, he will never give up, even if he is a hundred years old.’

A decade later, and more than twenty years after entering politics, Imran Khan became prime minister of Pakistan.

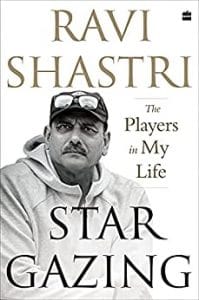

This excerpt from ‘Stargazing: The Players in My Life’ by Ravi Shastri has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publishers India.