The middle-class urban entrant to rural development came with a formula of action under certain heads: literacy, toilets and traditional malpractices. Self-styled reformers, who were very often genuine protestors against privilege, nonetheless came with all the additional baggage of superiority and arrogance. The initial interactions on literacy for women led to important understanding and earlier perceptions were constantly revised. For instance, learning a skill needs time; literacy is no different from, say, tailoring. An adult needs to see literacy as the acquisition of a skill, as a tool for establishing oneself.

Literacy classes ran at night, failing to acknowledge a woman’s physical incapacity to study after a hard twelve-hour workday, or to appreciate her intelligence. After coming to terms with the arrogance of the ‘let’s teach them’ attitude, the process was reversed. An experiment with literacy began with a woman’s real predicament at the centre of its concerns. We reckoned that women needed both time and space to deal with learning the skill. The programme for literacy at the Barefoot College, Tilonia, was designed by its women workers. Using an existing training capsule called Training Rural Youth for Self-Employment (TRYSEM) it was decided to dedicate eight hours a day for six months to a literacy training programme. Four women leaders, across caste and religion—Naurti, Mangi, Billan and Haseena—volunteered to attend the course, with a daily honorarium to compensate for loss of wages.

The early ’80s were days of intense learning for the four who came to learn a skill, and the dozen or so of us who came to be educated. The mornings were board, chalk and writing. Painful for these mature women who sometimes flung the chalk and asked instead for a shovel and the task of digging, where they were adults, skilled and competent. In the afternoons the positions were reversed. The women taught us the politics of gender in the village, its nuances, their understanding of power and oppression, their joys and how they sought expressions for liberation from oppression. We sang, laughed and enjoyed each other’s company. Women from other states working in Tilonia—Omana and Vidhya—who were part of this training began great programmes for women in Wayanad, Kerala, and Koraput, Odisha, respectively. Their initial orientation and ‘gurus’ were these extraordinary women from rural Rajasthan. At the end of those six months there was cross-cultural learning and the birth of collective women’s action, which lasted for decades.

Also read: For the West, the Indian village was ‘ever-present & never-changing’ – even Karl Marx wrote so

The Government of Rajasthan decided to build on this experience, as well as work in villages in Silora block, where Tilonia is located— women’s collectives in the village had begun to form effective groups. The argument that leaders cannot be created but can be identified and empowered with skills, and gaps in information attended to, gained ground. Anil Bordia, an enlightened civil servant working as development commissioner, inspired by this and other processes of empowering women, initiated the Women’s Development Programme (WDP). The mainstream discourse on feminism in India was burgeoning and WDP managed to bring in the essence of some of its arguments. The seeds of this expansion demanded a dialectic between action and reflection, as well as the ability to steer between the rigidity of a government programme and the flexibility inherent in an NGO experiment. It sought to bring the varied experiences with women’s activism together, within the structure and authority of government. The Rajasthan civil service, no different from other male-dominated spaces, was firmly entrenched between patriarchy and feudalism. But the WDP was a significant breakthrough. Women invited to plan the programme and design training were given space to bring in contemporary views on women’s issues as well as modes of exchanging knowledge and skills.

To quote from a ‘Pracheta Training’ report written with Dr Sharada Jain and the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Jaipur:

We talked without having mothers, fathers, officers, husbands around—with a sense of space. These voices around describe us in various ways, forcing us to see ourselves falling in strange brackets—almost shaping and moulding us …

This experience taught the ‘trainers’ as much as it taught the ‘trainees’ to open minds conditioned by prejudice, balance participation with self-appointed authority, to keep a separate identity as trainer and yet participate equally and fully.

There were sceptics, but as the training progressed many gradually lost their scepticism and a friendly and creative critique took its place. We lived together, challenging untouchability and prejudices of caste hierarchy. We shared stories of gender and the fear of violence, but in every other way—familial, social, economic and political—we were different. We had to be constantly vigilant so that our hackles did not rise while listening to issues that arose from a traditional and unequal belief in caste and religious prejudice. Women shared thoughts, feelings and predicaments. The sharing of these stories bonded us, as they have millions of women around the world. We became collectively exhilarated and responded holistically to reach out to each other. Reason and analysis followed these sessions to locate our political battles. To quote Dr S. Anandalakshmy, we were ‘thinking with our hearts’. What we learnt in the early 1980s is now accepted in theory and practice: political action is also born from intense personal sharing.

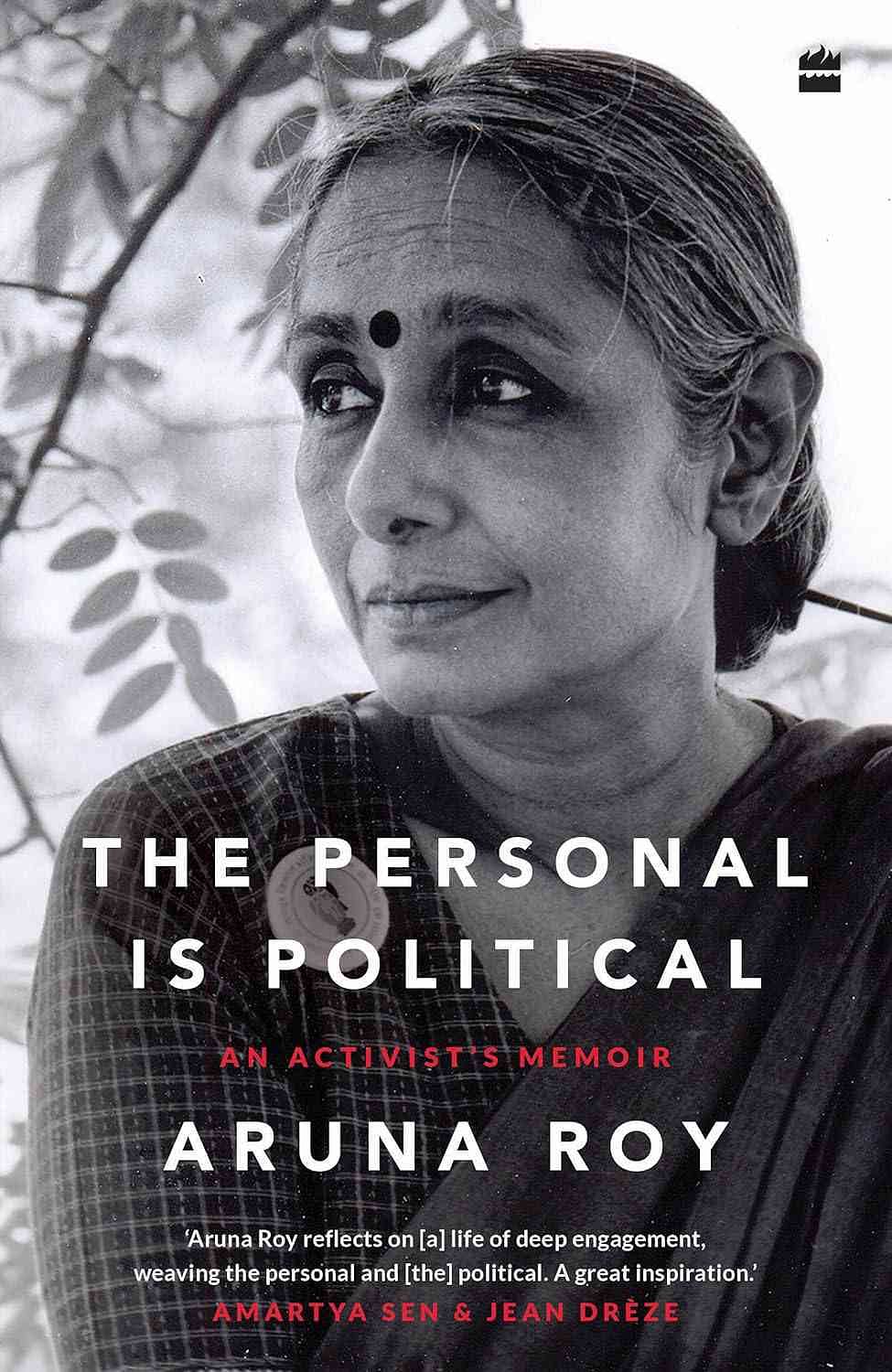

This excerpt from ‘The Personal is Political’ by Aruna R oy has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

oy has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.