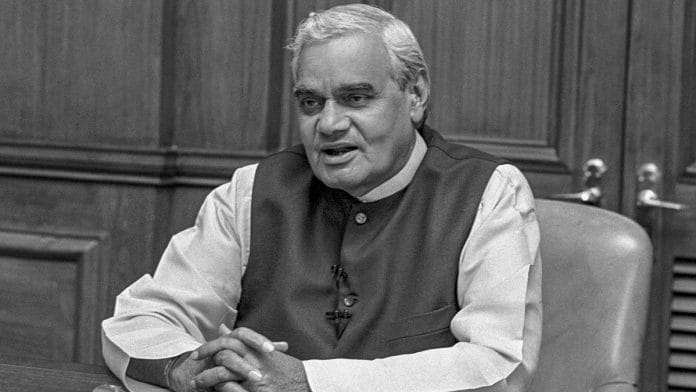

From a study of Atal Bihari Vajpayee as prime minister in his first term, 1998–99, or as a political leader during the 1996–99 span, what can one conclude about him? The problem is that like India, Vajpayee does not fit into easy characterizations. Was he a liberal? But wasn’t he associated with the RSS, an organization that is more commented upon than studied? Did he believe in secularism? If he did, why was he so strongly opposed to conversions? Weren’t economic reforms of his regime more by oversight than by design? But would that explain his courage in actually going ahead with the privatization of PSUs, a decision that was so revolutionary that the successor government, of Manmohan Singh and P. Chidambaram, who obviously understood its logic, lacked the political will to execute it? In fact, they not only stopped it but undertook to criminally prosecute those who had gone ahead with privatization.

What makes Vajpayee difficult to understand is that he never seemed to have articulated his beliefs in a systematic way. How then does one better understand Vajpayee’s world view?

One can start by looking at his initial choice of finance minister, Jaswant Singh. Rightly or wrongly, Singh was identified as a believer in economic liberalization and the private sector. It is another matter that he could not make it, having just lost the elections to the Lok Sabha. Yashwant Sinha, who actually became Vajpayee’s first finance minister, was initially seen as a candidate backed by the swadeshi lobby but whose actions very soon showed him pushing the reforms agenda. Within weeks of becoming prime minister, Vajpayee had reassured the private sector by telling them that he came ‘from a political tradition that does not look upon commerce and industry with distrust. When it was conventional political expediency to decry entrepreneurship, we championed their cause.’

Two short but powerful examples of policy intervention in Vajpayee’s first term (March 1998–October 1999) and a personal example would help clarify Vajpayee’s approach to economic reforms. The first, already referred to, was the National Highways Development Project (NHDP), including the Golden Quadrilateral. For too long, Indian policymakers saw highways as catering to the narrow elite of car owners, even as long-distance cargo increasingly moved out of railways and went to trucks. Initially, the NHDP was seen as a bid to revive the demand for steel and cement, and to create construction jobs, but that was a narrow view. Vajpayee’s idea behind it was the creation of one Indian market where logistics would not be a constraint; the time and cost savings would be humongous and could help promote investment and competitiveness in the economy.

Also read: When Advani and Vajpayee founded BJP, they knew RSS needed to be kept at arm’s length

Once the rural connectivity component, the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, kicked in, the effect on rural society, not just on its economy, was almost revolutionary. It allowed small and marginal farmers to find a better market for their produce; lacking holding capacity, they were earlier forced to sell it locally at depressed prices. It allowed agricultural labour to move beyond their villages and find better wages. India’s elementary school enrolment increased markedly during this period. A lot of credit for this should go to the launch of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. But would teachers have shown up in rural schools if there were no, or poor, road connections? Going beyond the budget and making users pay part of the costs, including for rural roads, was again an ingenious idea.

Another shibboleth that had to be destroyed was that telecommunications served the rich and the upper-middle classes. The Narasimha Rao government had launched a telecom policy that allowed private players entry in the mobile services market. Possibly due to inexperience and bad advice by consultants, the initial demand was overestimated. Within a short period, the licensees whose bids had been accepted realized that they had all overestimated potential revenue. The massive mismatch between revenues realized and fees payable to the government meant that adequate investment did not take place. This, in turn, prevented licensees from lowering prices to attract more usage. Caught in this vicious cycle, it seemed that the telecom revolution would be aborted and become another case of missed opportunity.

The licensees had a legal obligation to pay up, since they had made the bids and had entered into a contract with the government to do so. It was argued that it was not the job of the government to rescue those whose business models had failed. After all, had they made profits beyond expectations, they would not have shared the windfall gains with the government. The whole logic of economic liberalization was that the government should not be involved in the business, and—as Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction tells us—those who could not compete should be allowed to die, so that underutilized resources could be released and be better used by somebody more efficient.

But there were two factors that could help one argue for the opposite case. It was not that a few individual companies were doing badly—as it was almost all of them across the country. Many successful bidders did not even begin operations. The Department of Telecommunications, which had to hand-hold the process, was not just a reluctant partner; it mostly worked to sabotage the entry of the private sector in what it saw as its own monopoly. It even stymied the efforts of the regulator who sought to ease the birth pangs of the telecom operators. In short, the issue was not of individual failure but one with systemic issues at play.

Also read: Jaswant Singh — communicator, crisis manager, man of letters and a student of history

The second feature that made the case for a relook at the license conditions was that there was a genuine fear that a single ‘knight in shining armour’ would emerge, buy up the distressed companies and effectively establish a monopoly. Therefore, if the government was looking at making systemic changes to help sustain the telecom providers, then it had to be done at a time when there were multiple players rather than a monopoly operator.

A participative approach was taken up. The government task force, headed by Jaswant Singh and comprising a large number of people representing different interest, asked for suggestions.

The unanimous suggestion was to move to a revenue-sharing model, but this was not without its difficulties. The telecom minister, Jagmohan, was completely opposed to it, arguing for upholding the terms of the contract. There were lots of articles written against the change, insinuating malfeasance. There was considerable opposition to this move towards revenue-sharing even within the government and in the cabinet. It was Vajpayee’s firm conviction and support that allowed the proposal to go through.

But that was not the end, since economic interests looking to monopolize the sector would not give up so easily. A writ petition was filed against the proposal in the Delhi High Court. The court ordered that the government could go ahead with it subject to parliamentary approval, even though in the Indian scheme of governance, it is the executive that determines policies exclusively. It is only when legislative changes are required that parliamentary approval becomes necessary. The telecom policy of 1994, which allowed private participation, did not go to Parliament. Since by now, the twelfth Lok Sabha had been dissolved consequent on the fall of the Vajpayee government, the actual change was affected only in late 1999.

its telecom revolution and highways as a given, but these did not come about by chance. That Vajpayee was not into the nitty-gritty of economic policymaking was well known; what is less well known was his almost libertarian view of the role of the government in not hindering the economic life of the community.

My in-laws used to stay in a rent-control house in Allahabad. The landlord used specific legal stratagem that allowed the release of such houses for self-use and promptly sold it. When I related this to Vajpayee, his answer was that the landlord, as the owner and investor, should have full discretion in how he uses his property.

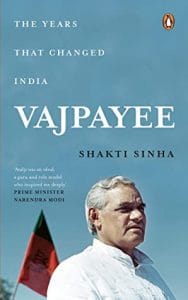

This excerpt from ‘Vajpayee: The Years That Changed India’ by Shakti Sinha has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘Vajpayee: The Years That Changed India’ by Shakti Sinha has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Vajpayee’s success with regard to the economy – as in most other things – lay in his ability to build a talented team of minsters and give them free rein. He was not insecure or wont to take credit or to project himself as some sort of superman who knew it all. He was not dogmatic, he did not seek to impose his own thinking on anyone. He listened to all shades of opinion and respected professional advice. He brought people together, united rather than divided them, gave credit where due, and thus motivated everyone to give their best. He invited trust and confidence, his motives were never suspect. That is why, despite lacking a majority for his own party in parliament, he ran a successful government of disparate parties from all over India for 5 years and delivered strong economic growth. Not only that, he did it when India faced a full blown war in Kargil and suffered severe economic pressure and global isolation for testing the nuclear weapons. Sadly, the tradition of dignified, competent governance that he brought seems to have gone for ever.

When I read Jugalbandi, the comparison that came to mind was Dev Anand. Both men became, in their own ways, stars at a young age. Vajpayeeji knew in his bones, when his party simply did not have the horsepower in Parliament, that he would one day become Prime Minister. When he showed the glittering lights of nighttime Singapore from the rooftop restaurant of the Shangri La Hotel to Jaswant Singh, telling him that it used to be like Calcutta before it was transformed by PM LKY, his thoughts must certainly have gone back to the Central Hall of Parliament. Of the insularity and licence permit raj that suffused its spirit. So why agonise whether he was a liberal, a free market guy, whatever. He was a good human being and a great Prime Minister. Travelled a long way in life from a humble school teacher’s home. Wanted his country to develop, his countrymen to prosper. As someone so fond of travel, he must have seen similar transformations in so many other countries as well. Have never understood why our leaders forget all the wonderful things they see in the rest of the world the moment they step on the sacred soil of Hindustan.

Vajpayee was truly India’s most liberal PM, both politically and economically. Unfortunately India has had the misfortune of being ruled for the longest periods by illiberal PMs starting with J. Nehru to the present incumbent. Except for PVNR and ABV. Not much is known about LBS, so he is excluded. The rest have ensured that even after 70 years India remains a desperately poor country with abysmal living conditions.