Truth be told, it wasn’t only the beast that decimated the hippie culture. The ongoing conflict in the Middle East and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan also hit it hard. But in 1976, after the Nepalese government banned cannabis, the hippie culture never revived completely. Cat Stevens probably never managed to see ‘Katmandu’ and experience the freakish life of grass and hash. He converted some years later to Islam and changed his name to Yusuf, an irony if there ever was one.

The intensity of his new conversion became evident when he was asked about Ayatollah Khomeini’s death fatwa against the author, Salman Rushdie. After Rushdie’s book, The Satanic Verses, was published, Khomeini, an Islamic religious leader, ordered the killing of the author for blasphemy against the Prophet.

Yusuf had only this to say—‘He must be killed.’

It is heartbreaking how killing and killers punctuated the hippie trail, which was once the route to freedom and salvation.

Once, a news channel asked Charles Sobhraj, ‘What makes a man a murderer?’

‘Feeling,’ Charles said, simply. ‘Either they have too much feeling and cannot control themselves, or they have no feeling. It is always one of the two.’

In all fairness, Yusuf ’s disillusionment with the hippie trail was not unfounded. Charles, the Satan of this trail, wielded strength and notoriety enough to make anyone wince. Years later, this Satan, however, would be busy measuring the amount of his urine in a small, white-tiled hospital toilet. He would pass out now and then, the plastic beaker with his urine slipping from his hands and spilling on the floor.

It was the year 1943, bang in the middle of World War II. Vietnam was war-torn, and, much like any other ravaged country, harboured many homeless children. One of these street children was Noi aka Tran Loang Phun. Children grew up quickly on the streets, hunger and the struggle for survival rapidly eating into their innocence. Noi caught the eye of a wealthy Indian man—a textile merchant who ran the Hatchand Bhawani Prasad Gurumukh Shop. Noi and the textile merchant fell in love, got married, and became parents to a baby boy in 1944. They named the child, Hatchand Bhaonani Gurumukh Charles Sobhraj.

But Noi and Hatchand’s marriage was doomed from the start. When he visited his home country, his parents forced him to get married to a girl from Pune in India. ‘I am sorry,’ he claimed when he was back in Vietnam. ‘If it’s any consolation, it was purely an arranged marriage. It’s not like I love her. You can still stay here as my wife.’

Noi and Hatchand separated. She eventually found a new beau—a French army lieutenant called Jacques Russel—and moved with her new partner to the cantonment. Charles remained with his father in Saigon. Noi’s firstborn was soon relegated to the status of the neglected child of warring, estranged parents—the child who didn’t fit anywhere.

Noi already had two kids with Russel and was pregnant with the third when he was called back to Marseilles in France.

Four years passed by before Russel and Noi got the chance to visit Vietnam. Charles wasn’t doing well. His days passed by in neglect, his father’s family paying him little attention. On an impulse, fuelled by a sudden burst of emotion for her first baby, Noi decided to take her son away to France. She would help him get a normal childhood, or at least, salvage what

remained of it.

But things didn’t go as planned. Charles was unable to bond with his new family in France. He would frequently lose his temper and lash out at his mother for separating him from his father. Eventually, Charles turned against his father too, for permitting his ex-wife to take him away. He detested the new ways of his life, the new man who was his mother’s husband and whom he was supposed to address as ‘dad’. He longed for his life back in Saigon.

It was then that this adolescent boy, for no apparent reason, started committing petty crimes. It would be theft one day, violence the other. He was frequently in and out of the juvenile prisons in France. Each time he was apprehended, his mother’s heart broke a little. She meted out harsh punishments for all his crimes; she wanted to do everything in her power to raise her son well. He wouldn’t live on the street as she had; he would have a respectable life that didn’t have anything to do with prisons. But her punishments only angered Charles further.

He got worse. Finally, one day, exhausted with their efforts to reform the boy, Noi and Russell gave up. Charles was sent to a hostel in Paris while they moved back to Saigon. He came to visit them a few times, a young boy of sixteen, his mind and face both equally unreadable.

Also read: Why some leopards become ‘crooked’ man-eaters—the conspiracies

By now, Charles was a hardened criminal. In 1963, he was caught for a charge of burglary and sent to the Poissy prison near Paris. His term in this Parisian prison was perhaps the last chance he had to pause—and reverse—the infernal storm taking over his soul. But he did not take it. Instead, he learnt to manipulate, to use his charming, seductive personality to get people to do his bidding. He managed to convince the jail authorities to bring him books on literature and foreign languages. He also befriended Felix d’Escogne, a prison volunteer and a wealthy Parisian. The two decided to stay together when Charles was

on parole.

While in Poissy, Charles got an intimate exposure to the criminal underworld of France. Felix’s friendship took him very close to the Parisian high society. This was not the society

Charles hailed from, but he fitted right in; his knowledge of literature and foreign languages wonderfully complemented his handsome personality. With feline grace and cunning, he clawed his way into this world, marrying crime and riches. He had to belong to this world now, whatever it took. To maintain the standards he wanted to portray to the world, he was in constant need of money. No wonder then that his favourite crimes—robbing tourists and breaking into houses—continued with increasing momentum.

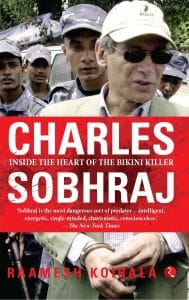

This excerpt from Raamesh Koirala’s Charles Sobhraj: Inside the Heart of the Bikini Killer has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from Raamesh Koirala’s Charles Sobhraj: Inside the Heart of the Bikini Killer has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.