For all its entertainment value, the North-South mango debate is the noise of two players arguing loudly when the match is taking place elsewhere. Bihar and West Bengal are even more taken with their mangoes. As Mumbai and Delhi have gained importance, becoming centres of political and financial might, Kolkata and Patna have lost out. Their elites do not have a comparable all-India voice and presence. But they have numerous fine mango varieties, even if the rest of India is clueless about them.

The only rival in fame to the Langda of Varanasi is the Langda of Digha, a Patna suburb. Here, they do not call it the Langda but the Doodhiya/Dhulia Malda. (Lesson in variety names: in West Bengal’s Malda, the same variety is called Laingda; in eastern Uttar Pradesh, it is called Kapooriya, a name also used for other varieties in other regions.) Like so many fine varieties, the Doodhiya Malda does not go to the market; connoisseurs go to the orchard and buy it right there at any price the grower quotes: I’ve heard `1,300 per kilogram east of Patna is Bhagalpur, where you get the flavourful Zardalu, a slender and delicate variety.

If you keep travelling along the Ganga’s south bank, you go past several centres of horticulture. There’s Pakur, a Jharkhand town with numerous old orchards; the mangoes here include fine mangoes developed from courtly patronage as well as heirloom varieties of forest-dwelling tribes. Northwest of here is Malda, a major centre of mango cultivation. Much of the rich mango-growing area beyond this point is now in Bangladesh.

About 60 kilometres downstream of the Bhagirathi/Hooghly, a distributary of the Ganga, is Murshidabad. It is perhaps the greatest centre in the history of fine mangoes. It’s worth a quick detour into history here. In the early eighteenth century, the richest province of

the Mughal Empire was Bengal; it included the states of Bihar and Odisha, along with what is now Bangladesh. In 1717, the capital of the province moved from Dhaka to Murshidabad. The city soon became the seat of the opulent nawabs of Bengal. Jagat Seth is a prominent title of the time, meaning ‘banker to the whole world’! The Mughal court gave this title to Seth Manikchand, an Oswal Jain merchant who used his banking network to deliver the Bengal nawab’s tribute to Delhi; thereafter, the title became hereditary.

The Jagat Seth family bank, the world’s wealthiest at its peak, became central to Bengal. At one point, the family ran the state treasury and had its own mint, controlling the financial markets and the thriving trade. Gradually, other Jain clans from Rajasthan joined them. Within a few decades, Murshidabad became the centre of all things wealthy and refined, from banking to architecture, from silken weaves to craft mangoes. However, the 1757 Battle of Plassey made the nawab irrelevant; the patronage of Murshidabad’s fine mangoes fell to the wealthy Rajasthani merchant families. The power centre shifted to the upcoming British city of Calcutta.

Also read: Langda, Kesar to Alphonso—how mangoes shaped art, politics & culture in India

It was in Kolkata that I met a suitable person to evaluate Murshidabad’s mangoes. Lata Bajoria was born in Mumbai in 1950 into a Rajasthani family. She was very keen on the outdoors; as a young girl, she climbed trees in the family’s mango orchard in Thane.

They had the best of mangoes available in Mumbai. Then, she was married into a prominent business family in Kolkata; among other things, it owned India’s largest jute business that she now runs.

During the summer, relatives in Murshidabad sent the Bajorias baskets of mangoes. ‘Each basket had a label with the variety’s name on it. I remember Bimli, Champa, Rani Pasand, and so many others. Each of those mangoes had a fascinating taste. They were like magic to me, I used to transform into a child, excited to see those mangoes, to eat them,’ she told me in the remarkable garden she has set up around her house on Garden Reach Road in Kolkata’s Khiddirpore area. I asked her to compare the mangoes she’d had in Mumbai with those in Kolkata. She said the Bengal mangoes were far superior in taste, variety, fragrance, and appearance to the ones she had had in Mumbai.

Over time, almost all the Rajasthani merchant families of Murshidabad moved to Kolkata. But their luxurious mansions and ornately-decorated houses still stand in the twin towns of Azimganj and Jiaganj on either side of the Hooghly, north of Murshidabad. Their relatives in Rajasthan called them ‘sheher wale’ because Murshidabad was the big city of the time, the centre of refinement. Subsequent migrants from Rajasthan to Kolkata also addressed the

older families of Murshidabad as ‘Sheherwali’. Some families retained their mansions and orchards in Murshidabad; even though they live in Kolkata now, they’ve joined hands to revive the city’s cultural heritage, forming the Murshidabad Heritage Development Society.

One of its activities is an annual mango festival in Kolkata to showcase Murshidabad’s fine mangoes and their attendant cultural refinement, like the ritualized cutting of mangoes by the Sheherwali women. Several members of the community say they cannot eat mangoes outside their house because they are not cut properly.

One of the prized varieties here is the Kohitoor. It is so delicate, legend says it was kept in cotton wool and turned every few hours so as to not put too much pressure on any one side and also to ripen it evenly. It was preserved in honey, its flesh cut with bamboo blades because metal was considered too coarse! Legends apart, I’ve met growers who still sell one Kohitoor mango for up to `800! Suchmangoes are, however, limited to Murshidabad and the Sheherwali Jains. Ordinary folk have not heard of or tasted them, which is why these mangoes are not a part of Bengal’s mango culture.

Bengal, though, is as passionate about the mango as any other region. ‘The mango tree is like a family member to us, like a friend or a neighbour,’ said Swati Bhattacharjee, senior assistant editor at the daily Anandabazar Patrika in Kolkata. ‘We count our years and seasons by the cycle of the mango tree. We do not say “how many springs”, we say, “how many summers of the mango” here,’ she said.

If a Bengali family has land, it is a given that they will have at least one mango tree; children develop their sense of adventure and nature by climbing mango trees to pluck the fruits: ‘Girls are especially fond of raw mangoes with salt and chilli powder.’ Her neighbours have a dog named Mango because when he was a puppy ‘he was so sweet!’

She mentioned some of the numerous ways in which the mango dominates conversations. ‘Bengalis love to discuss if this is a good year for yields or not. The price and quality of mangoes in the market is discussed obsessively. They describe in great detail the price they got, comparing it with what others paid,’ she said. The fruit of choice in most of West Bengal is the Himsagar, a very sweet variety with firm flesh, little fibre, and a hint of turpentine.

Then, there are the festivals! The sixth day of the month of Jyeshtha is called Jamai Shashthi, when Bengali families gift mangoes, jackfruit, and other fruits to the son-in-law. ‘A lot of mango gifting happens on that day, especially among those who own orchards,’ she said. During Saraswati Puja, the panchamrut mixture is slurped from a stone bowl, accompanied by the chewing of mango flowers.

‘It is the Michael Jackson of fruits, the mango,’ said her husband, Biprodas, who is a retired school teacher.

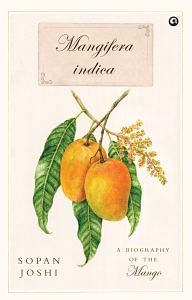

This excerpt from Sopan Joshi’s ‘Magnifera Indica: A Biography of the Mango’ has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from Sopan Joshi’s ‘Magnifera Indica: A Biography of the Mango’ has been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.