By 2004, the women of Kasturba Nagar in northern India decided that they had suffered enough. For more than a decade, Akku Yadav (born Bharat Kalicharan) had terrorized the three hundred families belonging to their community. Yadav and his gang had beaten, tortured, mutilated and murdered men, women and children. They had invaded people’s homes, extorted money and stolen property. Gang rape (often in public) had frequently been employed to humiliate and intimidate them. At least forty women and girls (some as young as ten years of age) had been sexually assaulted. In the words of one resident, ‘a rape victim lives in every other house.’

Yadav’s victims had attempted to stop him. Despite the formidable stigma attached to being raped, they had reported his violence to the authorities, only to find their complaints ignored by the police or dismissed by court officials. Yadav was skilled at manipulating men in power, bribing them with cash and alcohol. He was also of a higher caste than his victims, most of whom were Dalits (previously known as ‘untouchables’). His freedoms were valued much more highly than those of his economically struggling victims.

This changed in August 2004. Yadav had raped a young girl and demanded money from another. When Yadav heard that a 25-year-old Dalit woman called Usha Narayane had reported these actions to the police, he arrived at her home with forty members of his gang threatening to ‘throw acid’ in her face so she would no longer be ‘in a position to file any more complaints!’ He warned Narayane that ‘If we ever meet you, you don’t know what we’ll do to you! Gang rape is nothing! You can’t imagine what we’ll do to you!’ Narayane called the police. But, as had happened before, they never arrived. When she feared that he was going to break into her home, Narayane turned on the gas and threatened to blow up herself and her assailants. Yadav left, but the community decided that they had had enough. Hundreds of men and women picked up rocks and sticks and began attacking Yadav and members of his gang. After they burnt down his house, Yadav was taken into police custody for his own protection.

A few days later, on 13 August, Yadav appeared before the Nagpur District Court. When it became clear that he would be acquitted again, two hundred local women entered the courtroom. Yadav was full of bravado, threatening to teach each of them a lesson. When he called one woman (whom he had previously raped) a prostitute, she removed her sandal and began beating him, screaming that ‘We can’t both live on this Earth together. It’s you or me.’ At this point, the other women in the courtroom spontaneously rose up in fury. They overpowered the guards and court officials, threw chilli powder in Yadav’s face and cut off his penis with a kitchen knife. He was stabbed at least seventy times. Vigilantism was the only way these women could achieve justice.

None of the women were apologetic. They defended their lethal vigilantism on the grounds of ‘social justice’ and the ‘freedom struggle’. As trade union activist V. Chandra explained, ‘we have all waited for police to act, but nothing happens. The molestations and rapes go on.’ Activist Usha Narayane agreed, maintaining that the police and politicians were ‘in cahoots with the criminals’, providing them with ‘protection’. She asked

How are we in the wrong? Courts take ages to give a decision. We

may die before they give a decision. What is the point of going

to courts? We gave 15 years to the courts. Now, the women of

Kasturbanager [sic] have given a clear message to the courts. You

could not do it; we have done it. How are we in the wrong?

To people who criticized them, the women retorted, ‘there is no justice for the poor. What if this had happened to a minister’s wife or daughter? So, we decided to do it ourselves.’

A small number of women were charged with lynching Yadav but there was insufficient evidence to convict them. Even if the case had been pursued in the courts, the chance that these women would have been convicted was low: they were being hailed as heroines within the community. Hundreds of women were prepared to confess en masse to having carried out the murder. The retired High Court judge Bhau Vahane publicly supported the women, admitting that ‘they were left with no alternative but to finish Akku. The women repeatedly pleaded with the police for their security. But the police failed to protect them.’ A group of one hundred lawyers based in Nagpur announced that the accused women should be treated as victims, not perpetrators of violence.

By beginning this chapter with the vigilantism carried out by the women of Kasturba Nagar, I seek to draw attention to the difficulties that victims experience when sexual abuse is systematic and systemic, as it is for Dalit and Adivasi women in India. But I also aim to question assumptions that victims are passive subjects. When faced with the impotence of the law to remedy their grievances, victim-survivors can act with retributive fury.

But what about the negative side of vigilantism? The violent actions of the women of Kasturba Nagar cannot be compared with some murderous mobs elsewhere in India or in the usa, where thousands of Black Americans were lynched as a result of false accusations of rape. And what about formal justice? The law is not free from justified accusations of racism and classism. These prejudices were in part enhanced by the introduction of scientific experts into the courtroom. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the question as to whether perpetrators of sexual violence are ‘mad or bad’ has had a significant impact on punishment regimes. It could determine whether an offender was incarcerated or treated in a psychiatric hospital. Diagnostic classifications such as ‘paedophile’ and ‘psychopath’ have been employed in contradictory ways to ensure that violent men of colour are either denigrated as ‘degenerates’ (for which the only response is lifelong incarceration) or seen as not being psychically sophisticated enough to warrant psychiatric treatment.

Without understanding the compounding effects of caste, class, race and respectability, it is impossible to understand the differential punishments handed out to boys and men who act in sexually aggressive ways.

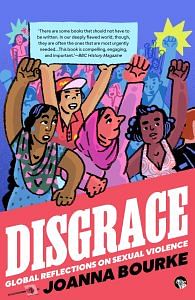

This excerpt from ‘Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence’ by Joanna Bourke has been published with permission from Speaking Tiger.

This excerpt from ‘Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence’ by Joanna Bourke has been published with permission from Speaking Tiger.