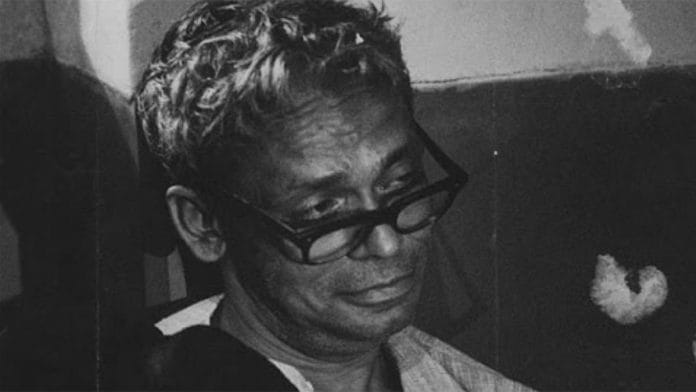

During Ghatak’s stint as a guest lecturer, Jagat saw that he was a mesmerizing teacher, with that extra spark that inspires and ignites students. Ghatak was on top of his filmmaking game at the time, having made three brilliant films in three years, Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), Subarnarekha (made in 1962, though not released until 1965). But few recognized his brilliance. During his entire lifetime, his films, with the exception of Meghe Dhaka Tara, were largely ignored by Bengal’s filmgoers, and even the response of critics was at best lukewarm.

With his filmmaking career ground to a halt, Ghatak needed another source of income, so when Jagat invited him to Poona—supervising the making of the diploma film Rendezvous was one of his first assignments in late 1963—he readily agreed. In Ghatak, Jagat saw that elusive combination that he was always on the lookout for in his teachers—great filmmaking talent and generous time availability.

He admired his films enormously, and thought the Institute would benefit from having Ghatak on campus as often as he was willing to come. In particular he thought that Ghatak would help improve the quality of the Institute’s programme of experimental films— the films Jagat encouraged his academic staff to make.

Jagat saw research and experimentation as the lifeblood of an academic organization and valued the edgy sense of possibility that such a programme brought. He believed it was crucial that staff members remain active filmmakers and not allow their filmmaking skills to get rusty. What’s more, these films were good opportunities for student participation, just as the first of them, Michel Wyn’s One Day, had been. And when they won awards, the prestige that accrued to the Institute helped burnish its reputation.

Later years would see more such award-winning films from the professors at the school—Editing professor R.K. Ramachandran’s f ilm Rains won an award at the Melbourne festival, and Cinematography professor C.V. Gopal’s film Rain and Shine participated at the Edinburgh Festival.

Ghatak found this experimental film programme extremely attractive. Here was a place, away from the mean-spirited tribe of commercial-minded producers, where every professor was being given an opportunity—and expensive celluloid and shooting facilities—to actually experiment.

So when Jagat first sounded out Ghatak in 1963 on the possibility of joining the Institute as the Vice Principal and Professor of Direction, he was interested. But Ghatak’s salary requirements were too high, and the job went to someone else, the Marathi filmmaker Ram Gabale, who was himself given a generous salary, just not as high as what Ghatak wanted. Ghatak, in the meantime, continued to visit the Institute as a guest lecturer.

Also read: Caste and kotha didn’t go together. It freed many lower caste girls

Gabale’s stint at the Institute was short—barely a year—falling prey to the inevitable itch for active filmmaking. He left towards the end of 1964 and that job lay vacant for some months, until, by mid-1965, Jagat was able to hire Ghatak.

Ghatak’s tenure would be even shorter than Gabale’s, lasting less than four months, from 5 June 1965 to 30 September 1965, curtailed not by an itch for filmmaking, but sadly, an addiction to alcohol. What his tenure lacked in length, however, it made up for in the impact he had on the Institute, which has always been accorded a prominent place in its history.

During Ghatak’s visits as a guest lecturer Jagat had come face to face with his one big drawback—‘his vice was drinking and more drinking.’ Perhaps the failure of his films had exacerbated his habit. Why then did Jagat seek to make Ghatak the Vice Principal, in effect his right-hand man?

He could easily have continued with the off-and-on guest-lecturer routine, but instead he fought vigorously to get Ghatak a full-time appointment. The reasons reveal Jagat’s character, and perhaps, one of his weaknesses.

He was an eternal optimist, he saw possibility in everyone and was inclined to think he could make anything happen— in this case, he probably thought he could ‘manage’ Ghatak’s drinking sufficiently to keep him functioning. I don’t think he had any illusions of fixing Ghatak’s drinking habit—he housed him in the Institute’s guest house to ensure that Ghatak was physically safe. But the larger reason was that he simply wanted the best for the Institute and he couldn’t let a ‘master of cinema’, as Jagat saw him, slip through his fingers without giving him a chance. If this was the man who made Meghe Dhaka Tara and Subarnarekha, then he wanted some of that skill and sensitivity to be transferred to his students. If the Institute’s mission was to impact India’s larger film industry—it certainly was Jagat’s—then he saw Ghatak as a tool to do so.

Emotionally gripping, Ghatak’s films were stories of human drama that unfolded in epic fashion, with characters who had their feet on the ground, even as they inhabited a page of history marked by the social and moral fallout of the 1947 Partition. The films were ripe with melodrama and coincidences of the sort you found in commercial cinema—a lost son randomly meeting his mother moments before she died and learning he was low caste; a sister turning to prostitution, waiting for her first customer, when in walks her estranged brother (both scenes from Subarnarekha)— but it was the cinematic treatment that was different. Shot realistically, mostly on location, the films had no clipped-on glamour, no ham acting, just a captivating lyricism.

All of this explains why Jagat wanted Ghatak for the Institute. But why did Ghatak want the Institute? When Jagat hired him, Ghatak had hit rock bottom. He had no work except for a stranded film project, Bagalar Banga Darshan. He had three small children, a wife who was unwell, and he was broke. A job at the Institute would provide him with not just a regular salary, but also the opportunity to participate in the Institute’s experimental film programme, a big lure, as making films was like oxygen to Ghatak.

He described his rationale in his letters to his wife, Surama, who later published them in a book. On 17 December 1964, while still a guest lecturer at the Institute, he wrote to her: ‘Here I am getting affection from everybody. This is the only place in the world which is left where people want me. Murari said I can join any time.’ On 27 December 1964, when Ghatak was quite sure of getting the Vice Principal’s job, and was planning to go to Calcutta to wrap up a film project, he wrote:

My only focus will be to finish Raman’s movie [Bagalar Banga Darshan]. After that I don’t want to make any more movies. I don’t like Calcutta any more. Here in the Institute I will have a fixed salary, respect, and can do the work that I want to. If I join before the summer vacation I will get an opportunity to go to Afghanistan for two months to do an experimental film.

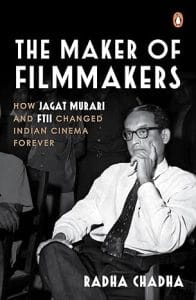

This excerpt from ‘The Maker of Filmmakers’ by Radha Chadha has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘The Maker of Filmmakers’ by Radha Chadha has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.