Hardayal Singh and his wife Kalyani were my maternal great-grandparents. They had converted to Christianity before my grandmother was born. I was vaguely aware of the circumstances that led to their conversion. However, I hadn’t delved much into the politics and sentiments behind the decision. My quest to find out more about my ancestors led to deep personal disappointment at the dearth of research and archival material available on Bhantus.

Through my limited exposure to our past, I understood that Bhantus were a tribe of feared outcastes, but the gaps in their recorded history was a sad reminder that perhaps their narrative was limited to the labels stamped upon them by the colonial government and the upper-caste society. Most research led me to a generic labelling of Bhantus with repetitious descriptors, such as thieves and petty criminals. I struggled to understand whether the entire community was indeed ‘criminal’, as labelled by the State, or were they merely victims of a biased and oriental stereotype. Either way, it was apparent to me that Bhantus themselves had little agency in matters of their own representation.

The word Bhantu or Bhatu is an aberration of the word Bhati. The community traces its lineage to the Sansi tribe. The Sansis derive their name from their Rajput ancestor called Raja Sansamal. The Bhantu samaj (society) split into two main branches. The first one being Bhantu Biddhu and the second one were Sansi Bhantu. The Sansi Bhantus further split into three subgroups, the first being called Bhantus, as found in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and the Andaman Islands. The second group called Karwal resided mainly in UP and Bihar, and Berias, the third subgroup, in Maharashtra and West Bengal.

Though one may find different sets of opinions regarding the origin of criminal tribes, there is good reason to believe that, like many other indigenous tribes, the Bhantus were once the original inhabitants of India. They are called by various names like Sansis, Sahasit, Bhantu, etc. The Sansis call themselves Bhantu in their local dialect. Some historical accounts, including the one my ancestors adhered to, suggest that all Bhantus are Bhati Rajputs driven out of Rajasthan by Muslim invaders.

Their social decline is linked to the siege of Chittorgarh by Allahuddin Khilji in 1308 CE. To save themselves from being converted to Islam, Bhantus resorted to burglary and theft as a means of livelihood. They had wandered all over Punjab, the erstwhile Northern Rajputana and the Central Province, where their fortunes changed drastically for the worse over the next two centuries.

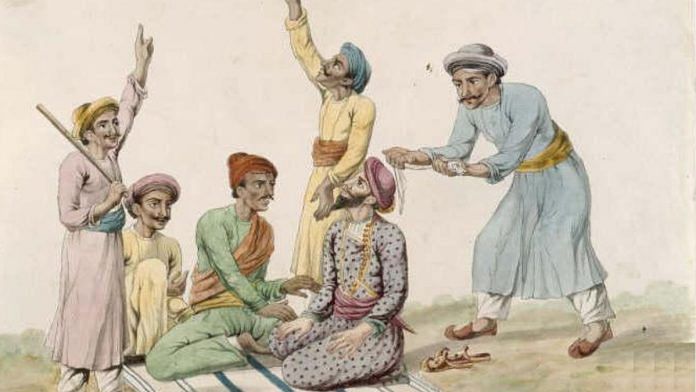

Eventually, some of them acquired status and influence by getting absorbed into local communities and Rajput armies or by adopting indigenous caste names. According to Dakxin Chhara, a distinguished scholar–activist and documentary film-maker, who himself belongs to the Bhantu community, the lineage of the Bhantu tribe predates the era of Mughal dominance in India. Bhantus tribesmen were mostly nomadic and their professions ranged from being street performers to pastoralists. For countless centuries, they roamed the Indian lands, and were one of the earliest inhabitants of the nation.

Despite this, he says, they did not associate with Hinduism and, as a consequence, remained outside the boundaries of the varna system, regrettably being forced into an untouchable status within Hindu society. However, like most Bhantus from Rajasthan, Hardayal Singh also shared a profound association with Rajputs. This association, no doubt, had influenced their lives and experiences in small but significant ways, even in defiance of social norms. For example, my great-grandfather sported the handlebar moustache, a trademark Rajput symbol–a clear concession granted to him from the upper-caste community, because his ancestors were once part of the Rajput army.

For Rajputs, the moustache is symbolic of a soldier’s honour and pride. This otherwise simple moustache can lead to murders of Dalit men in Rajasthan if they are seen sporting one, therefore, this was considered a well-earned favour by his community. While holding on to upper-caste associations in a highly casteist society is integral to social projection of status, Bhantus rarely enjoyed any real privileges that come from being a Rajput in Hindu society.

As a proud Bhantu, my great-grandfather used to regale his children with captivating tales of Bhantu heroism and bravery, and how in the past they had risen against the oppression of the British and the caste Hindus. In every Bhantu narrative, they saw themselves not merely as thieves but as contemporary Robin Hoods—redistributing wealth from the affluent to uplift the poor. Interestingly, some even consider themselves freedom fighters.

Bhantu elders are known to have shared their contribution in the freedom struggle by acts of providing shelter and security to freedom fighters and also by disseminating their messages from one place to the other, often through their songs. However, despite their honourable aspirations, history rarely remembers Bhantus as having such noble rectitude. Their contributions to the freedom struggle faded from public memory with the passage of time, leaving only their exploits that are remembered as acts of thuggery.

Popular culture and modern-day cinema have only perpetuated the oriental perception of the so-called criminal underclass and criminal tribes. ‘Blockbusters like Gunga Din (1939) to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) periodically resuscitate this stereotype.’ Nevertheless, within the Bhantu community, the stories of their struggles against injustice and inequality continue to be cherished and carefully passed down from one generation to another, reminding them of their resilient spirit and their ancestors’ unwavering commitment to the fight against oppression and even their contributions to the freedom struggle.

From 1871, Bhantus were one of the 150 tribes that the colonial British government had notified as ‘criminal tribes’.

In the middle of the 1800s, the British government initiated an expansion of their taxation efforts to the distant regions of India. They started a revenue system by taxing Adivasi (tribal) communities. This revenue collection system had the unintended consequence of disrupting various societal customs of these tribal populations. It brought ‘repressive intermediaries such as tax collectors and jagirdars (landlords) to collect revenue on behalf of the British regime, giving rise to many conflicts between the tribals and the British state’. The oppressive nature of this system, combined with these conflicts, motivated tribal groups to actively participate in the 1857 rebellion against the British colonial rule.

In the aftermath of the Revolt of 1857, the British became increasingly suspicious of nomadic tribes and people who did not own land, prompting heightened surveillance via various methods including the Thuggee (Act XXX of 1836) and Dacoity (Act XXIV of 1843), and later through the series of Criminal Tribes Acts from 1871 onwards. The ‘newly imposed forest laws and revenue policies made many nomads destitute, pushing them into petty crime for sustenance, which further reinforced the idea of hereditary criminal traits’. These actions were part of the colonialists’ tactics to exert control over the colonised population, casting them as suspicious individuals in their own homeland.

This excerpt from ‘This Land We Call Home: The Story of a Family, Caste, Conversions and Modern India’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘This Land We Call Home: The Story of a Family, Caste, Conversions and Modern India’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.