24 June 1983: It began as another ordinary day. Schools had closed for the summer and the family was visiting relatives in Delhi. There was a palpable buzz across the country – Kapil’s Devils were looking to make history against the West Indies in the Cricket World Cup final the next day, in what had been an unbelievable journey by a band of accidental heroes.

At Pratap Bhavan on the dusty Nehru Garden Road in Jalandhar, it was an easy Friday. This was the hub of two daily publications – the Urdu newspaper Pratap, and its Hindi-language sister, Vir Pratap.

What happened next not only shattered the morning calm, it left a scar that has never healed.

At 11 a.m., the peon – as was the practice – brought dak from the post office which was a few hundred metres away. As per usual, it was kept on my desk. Among the letters and newspapers, there was a parcel wrapped in white cloth that was addressed to my father, Virendra, the chief editor of both papers. I picked it up and saw that it was sent from a post office in the Amritsar district, but I did not pay much attention to it. Packages like this were not unusual in our office. After going through the rest of the mail, I tried opening the parcel, but it had been hammered shut with so many nails that I gave up. Thinking that it must be the usual propaganda stuff that newspapers were being flooded with in those days, I called a peon to take the parcel and open it, and then bring it back. I then forgot about it. Ten minutes later, there was a loud explosion in the room next to mine. The package had exploded – three employees were grievously injured, two of whom died in the nearby Civil Hospital.

It was the first time a parcel bomb had been used as a weapon in Punjab, as the country learned of a new terror modus operandi.

The powerful blast shook the double-storeyed building; windows were shattered as the explosive disintegrated into debris that went flying across rooms. The next morning’s editorial by Virendra, Pratap’s owner, spoke of how it was an attack in waiting.

Antt wohi hua jiska khatra tha. Vigat dedh varsh se jo patra mujhe prapt hue hain unse spasth tha kee kuch na kuch toh hoga. Abhi teen din pehle hee mujhe ek patra prapt hua tha … Jin hone yeh kaam kiya hai veh bahut galat fehmi ka shikar ho rahe hain. Yadi veh samajte hain ki is tarah veh Pratap aur Vir Pratap kee zuban band kar denge, yeh gardan kat toh sakti hai jhuk nahi saktee.

What transpired in the end was what we had feared. From the letters I had received over the last year and half, I knew something would happen. Just three days ago I received another letter … The perpetrators are under a grave misconception if they think that they can shut the voice of Pratap and Vir Pratap through this act. This neck can be cut, but it will never bend.

Through the haze of shock and panic, the three injured employees were rushed to the closest hospital – all three were below the age of thirty and had families to take care of. Krishan Alang died before they could reach the hospital, while Indresh Kumar was operated on for six hours, but did not survive either. Both victims left behind a young wife and a child.

I distinctly remember that one of the employees, Indresh Kumar, whose stomach had been ripped wide open by the explosion, spoke to me through his blinding pain as we rushed him down the twenty steps of the office saying, ‘Sir, I have also made a sacrifice for the country.’

The rest of the day went by in a blur of hospitals, post-mortems, grieving widows and cremations. Meanwhile, a huge crowd gathered outside Pratap’s office where an acquaintance overheard a group of men murmur regretfully, ‘Oh, taan bach gaye (the Pratap editors have escaped).’ They were strangers, but this was Punjab in 1983 – on the razor’s edge, only to succumb in the coming years as the ‘they’ and ‘us’ rhetoric tore the state apart.

A mention here of an old friend Harbrinderjeet Singh Dhillon, popularly known as Harji, who stayed with me throughout the day. We had great differences of opinion; I suspected him of having a sneaking admiration for Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, an obscure Sikh preacher turned dreaded militant, who was instrumental in starting a process that destroyed peace in Punjab – the folly of appropriation that haunts India – and his extremist policies. Yet, throughout the traumatic day, he was next to me like a pillar. I even urged him to leave, fearing there may be a mob backlash, but he stood his ground. So, all was not lost.

Niraja Mohan, Chander Mohan’s wife recounts:

I was visiting my parents in Delhi with my children when a phone call came from Harji. As he was narrating the news of the bomb blast, the phone line went dead, as was often the case with STD calls in those days. I was barely able to hear that my husband was safe. The kids and I rushed back to Jalandhar, where the driver met me and said, ‘Sahib bach gaye (Sir has survived).’ There was relief, but there was also sorrow that two innocent employees had been killed. It was an incident that shook not just the family but also Punjab’s dynamics.

In a vitiated atmosphere, Punjabi-language newspapers published from Jalandhar – a historical ancient city, where a majority of Urdu and Punjabi press settled post-Partition – did not condemn the incident. The owners of Jalandhar newspapers were a friendly bunch; yet not a single representative from a Punjabi daily called to condole the deaths at Pratap. Basic civility and the famed Punjabi brotherhood had become a casualty of the attack.

Who sent Pratap the parcel bomb? No answers have been forthcoming to date, nor was the family ever given any official response. The matter was closed after a shoddy investigation and all queries were stonewalled. It was concluded officially that the attack was the handiwork of extremists; however, without the clarity of a proper inquiry, it was based on presumption. Terrorism could not be ruled out either, but a lot more was floating around Punjab in those days. There was also an attempt to keep the communal pot boiling. Were we the victims of this conspiracy?

A foreign ambassador to India met the family and said, ‘If I was in your place, I would have gone running till I reached a safe place.’ And yet, despite two lives being sacrificed, thoughts of abandoning Punjab and the newspaper were furthest from the family’s minds. Displaced from Pakistan, there was no question of relocating again within India.

Warnings from the police to shuffle daily travel commutes intensified. The distance between the residence and office was barely a three-minute car ride, and did not give much scope for improvisation. On a fateful evening not taking the police’s advice nearly backfired as Virendra was involved in a high-speed chase by an unknown vehicle.

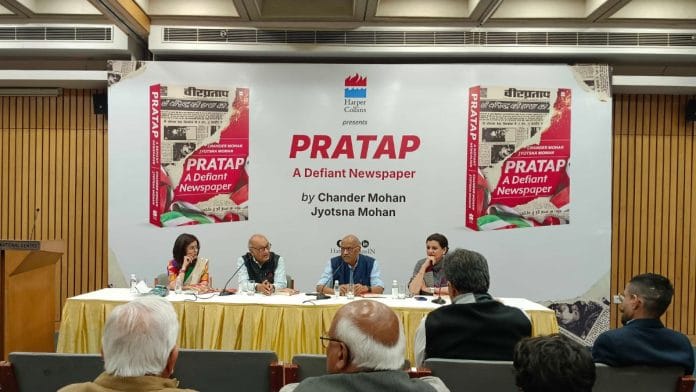

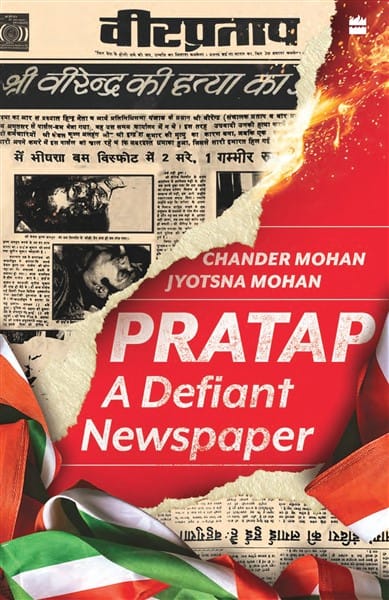

This excerpt from Pratap: A Defiant Newspaper by Chander Mohan and Jyotsna Mohan has been published with permission from HarperCollins.

This excerpt from Pratap: A Defiant Newspaper by Chander Mohan and Jyotsna Mohan has been published with permission from HarperCollins.