In Italy I met several young Bengali and Punjabi migrants who had run away from home after quarrelling with their families; they had almost inadvertently stepped on a migratory conveyor belt that had carried them all the way to Italy. One such journey was that of a fourteen-year-old Pakistani boy who had fought with his father and run off to the local railway station. In another era he might have spent a few weeks with relatives in another city before returning to his parents. But this being the age that it is, he had fallen in with a group that was starting a long overland journey across Iran and Turkey to Europe. After surviving many close brushes with death on the borders of Turkey, he had ended up in Rome.

I also met several former farmers from Pakistan whose lands had been swamped by the Jhelum floods of 2014. In the past they might have moved to a different town or tried to rebuild their lives after the floods had receded. But such is the present time that they too decided to set off for Europe instead; to them that step did not seem at all drastic, which is a measure of the degree to which these journeys are now seen as normal and not at all out of the ordinary.

It is, of course, not unusual for migrants to develop apprehensions on the road. But very few are able to abort their passages, usually because they are prevented by their guides, or their cohorts of fellow migrants. But generally the consideration that keeps them from turning back is, simply, pride, or the fear of being regarded as a quitter or coward.

In speaking to migrants, I often had to remind myself that most of them were of an age when it comes almost naturally to court dangers of a certain kind, as, for instance, ‘extreme adventurers’ do when they toboggan down the slopes of active volcanoes or rappel through canyons. Indeed, for a certain kind of person danger is not a deterrent but an incentive.

Conversely, in some societies, the willingness to brave certain dangers has long been regarded as a necessary step towards adulthood: thus, since ancient times, ordeals of various kinds have regularly served as life-cycle rituals. Today, in those parts of the world where it has become commonplace for young people to make difficult overseas journeys, migration is sometimes viewed through a similar prism, as a step towards being recognized as a fully fledged adult, capable of supporting a family.

Also read: A martial art tradition from Punjab that was banned by the British

These analogies may sound far-fetched, or even frivolous, in relation to migration. But consider the case of Davide, a Cameroonian who succeeded in migrating to Europe by scaling the heavily armoured fences that surround the city of Ceuta on the coast of Morocco. Along with Melilla, Ceuta is one of two Spanish enclaves in Africa; migrants who manage to set foot in either city must, by law, be treated as though they have stepped on European soil. Both cities are surrounded by trenches and several layers of fences topped with razor wire; they are also guarded by large contingents of Spanish and Moroccan soldiers, armed with all the most advanced equipment.

Davide, who left Cameroon in September 2013 at the age of twenty-five, was interviewed in Madrid in 2018 by David Kestenbaum of National Public Radio. In Kestenbaum’s words: ‘Davide describes the whole thing almost as if he were a kid setting out on an adventure… Unlike a lot of people trying to get from Africa to Europe, he said he wasn’t persecuted back home. He wasn’t starving. He wasn’t fleeing violence. He was just curious about the world and excited to see it.’

Davide’s journey took him from Cameroon to Algeria, and it was there that he learnt that instead of crossing the Mediterranean he could also reach Europe by climbing the fences that surround Ceuta and Melilla. So Davide travelled to Morocco and joined the large throngs of would-be migrants from all over Africa who camp near the two cities and periodically attempt to cross over.

‘At the beginning,’ says Davide, ‘my opinion was, well, you know, I’m a pretty brave guy, and … I like challenges. I thought I would do it in one try. I’m going to take it on with a lot of optimism, because that’s the type of person I am. I usually do things the first time I try them.’

Davide’s first attempt to cross the fences was encouraging because he managed to get past a trench and even reached the third barrier. ‘I don’t know how to express it, but it was something strange. I was thinking, I’m going to do it. Then I thought, I can’t do it. And then I was doing it, so I said, well, this is how it’s done. I’m doing it. I’m doing it. But I don’t know how to express it. That’s the truth.’

Here Kestenbaum interjects: ‘Did it feel like a crazy sport?’

‘Yeah,’ answers Davide, ‘exactly! That’s exactly what it is. The way you put it. It was a weird sport.’

But Davide’s first attempt failed, as did many others. A year went by and doubt began to creep in. ‘Why am I doing this? What good is this? … I thought about just abandoning everything, and I would cry.’

But it was the fences that held him there. ‘It’s something more than a fence. I know it may seem silly but there is something mystical in this fence. I’ve seen people who, when they get in front of the fence, they can’t move … There must be a spirit inside the fence that tries to prevent things. It’s really something very powerful. It’s not just a fence.’

After two years of failed attempts, Davide finally succeeded in crossing over. But his joy did not last long. ‘When I realized that I had made it, it was like a vacuum. That’s the truth. When we are in Morocco, we think that whenever I manage to get there, I’m going to be very happy. But once you make it you don’t feel anything. The feeling ends.’

Davide’s experience is a reminder that the idea of the ordeal has always held a certain fascination for human beings. This is why for many migrants their journeys become the defining moments of their lives. This is, in a way, the strangest aspect of their plight: in Europe they are confronted with the political rationality of a certain kind of liberalism that confers its sympathy only on victims. So in dealing with the state, and when talking to activists, they learn to present themselves as victims, as objects without agency, propelled solely by external forces. Yet in their own eyes, as in the eyes of their families back home, they are heroes who have taken their destinies into their hands and endured terrible ordeals. No wonder then that many of them say that the worst part of their journeys consists not of their time on the road or at sea, but rather of the months and years they spend languishing in European migrant camps. In those camps there is nothing to do but wait and sleep: it is little consolation that you are fed and housed and given allowances; it is the waiting and the idleness that break the spirit.

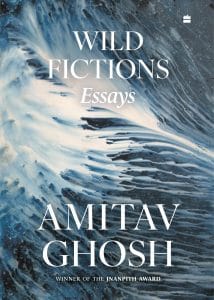

This excerpt from ‘Wild Fictions: Essays’ by Amitav Ghosh has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publishers.

This excerpt from ‘Wild Fictions: Essays’ by Amitav Ghosh has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publishers.