The first I heard of COVID was in the newspaper – like everyone else. It must have been the middle of January 2020. Reported first in Wuhan, it was spreading fast through China. We learned that it was caused by a virus of the coronavirus family, which includes strains like Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). The mortality rate was lower than for Nipah but the infectivity rate was extremely high, and the symptoms were very similar to those of other influenza viruses. This new strain was being called the novel coronavirus or SARS-CoV-2 (SARS coronavirus 2). Later, the WHO would name it Corona Virus Disease 2019 or COVID-19.

Viruses are cohabiting entities that can cause diseases stretching all the way from the common flu to more serious infections like COVID. There is a plethora of viruses that we haven’t even discovered yet, and most are not likely to be dangerous. But when something causes an imbalance in nature and a virus becomes infectious, the results can be deadly, as with the Spanish Flu of 1918 in which some 50 million died. After the experience with Nipah, every time someone mentioned an infectious disease, my antenna would go up. But in this particular case there was another reason. Kerala had a Wuhan connection.

A year before, I’d met some medical students who had applied for an internship with the government. They were students from a medical university in Wuhan. It stuck with me because it was a Chinese city, and I hadn’t realized till then that there was a contingent of Malayali students over there. When I read about this new disease in the newspaper and remembered our students in Wuhan, I called the health secretary, Rajan Khobragade, immediately. Rajan said we should be worried. Vacation season was starting in Wuhan, and during their holiday, Malayali students would be coming home to Kerala. What should we do? We were already planning a Nipah mock drill at that time, and we decided to also use it as a dry run for dealing with a new virus.

Also read:

On 24 January we formed a rapid response team and decided to open a control room in the office of the director of health services, making the DHS the nodal officer for the control room. In the control room we created eighteen expert groups, which looked at various tasks that are part of the larger strategy, such as logistics, quarantine, isolation, contact tracing, etc. Good officers were picked from each district and we gave them specific roles; training started in hospitals all over the state. If the coronavirus arrives on a flight, what should we do? That was the context of our groundwork. At the time many people made fun of us. A viral infection was spreading in Wuhan, a city in China that no one had heard of at that time; most people didn’t think it would ever become anyone else’s problem. ‘Why are you overreacting?’ they asked. ‘Are you looking for attention? We can deal with it when it comes, stop creating hype.’ We heard all sorts of things, from criticism to bad suggestions. But we just went ahead and did what we thought we needed to.

By 26 January 2020 the Kerala health department had issued a circular titled ‘nCorona Guidelines’ which analysed all the information available till then about this new virus and enunciated response procedures. This document covered everything from safety protocols for collecting samples, pre-hospital preparedness, surveillance and contact-tracing guidelines, and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for field surveillance of asymptomatic passengers under home isolation; it even stated the protocol for sending daily health status of passengers under observation. Depending on whether one saw the glass as half-full or half-empty, you could say we were either prophetic or fearful, but the fact is that we were the first in the country to create a novel coronavirus combat plan, even though we were not sure then if a plan was required. One of the key components of the nCorona Guidelines was the ‘Algorithm to be followed in case of suspected coronavirus cases’. It set out the procedures to be followed for all passengers whose travel originated in China.

Even though Kerala is a small state, given the vast number of Malayalis who live abroad, it has four airports. And we had medical teams at each one so that people could voluntarily declare any symptoms. On 27 January, a passenger flight arrived in Kochi. We already knew that some people on that flight were medical students from Wuhan. Airports come under the jurisdiction of the Airports Authority of India, and since the central government still hadn’t declared universal contact tracing, we couldn’t get the details of the passengers at the airport. But once the passengers came outside, the medical teams checked them. And because we did that, we found three symptomatic students. All of them were quarantined and tested for the novel coronavirus. On 30 January at 7 p.m., I was participating in a programme in Thiruvananthapuram called ‘Night Walk’. It was an initiative of the women and child development department, which was a part of my ministerial portfolio.

We had started a women’s empowerment programme called ‘Be brave and go ahead’. Even in Kerala, there is a notion that it is dangerous, or even inappropriate, for women to be out alone very late. The Night Walk was meant to persuade women that it is their right to be outside whenever they wish; the time of day shouldn’t be chosen for them. We began the walk from Martyrs’ Square in central Thiruvananthapuram, heading for Gandhi Square about 2 kilometres away. I was walking at the head of the group when my personal mobile phone began to ring.

I had told my staff to contact me immediately when the results came. The call was from the Thrissur DMO, Dr Reena. ‘Madam, the sample has been identified as coronavirus,’ she said. I remember that I immediately stopped walking, and the person next to me stopped as well. Even as we had prepared for the worst, I had been hoping the results would turn out to be negative. It was not to be. Kerala had become the first state in India to record a novel coronavirus infection. I left the walk right there, telling T.V. Anupama, director of the social justice department, to take my place and keep going with the rest of the group. After calling Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan to update him and ask his permission to leave for Thrissur immediately, I returned to my residential quarters and told my personal assistant, Pramod P., to arrange travel to Thrissur.

In a crisis, Pramod is always a clear thinker and able to work out simple, effective solutions for me. And he pointed out that in a car it takes more than six hours to traverse the distance of more than 270 kilometres from Thiruvananthapuram to Thrissur. At the time it was already 8 pm. He suggested an alternative: there was a flight to Kochi at 9.30 pm; if we took that we could travel to Thrissur – about 85 kilometres away – by road, getting there by midnight. I felt I should also notify the ministers from Thrissur district. So, while Pramod hunted for tickets, I spoke to A.C. Moideen, Sunil Kumar and Raveendranath. Two of the ministers said they’d come with me, while Raveendranath, who was in Kozhikode at the time, said he would travel from there.

The health secretary Rajan Khobragade also accompanied me. We didn’t even have time to eat; we left straight away to catch the flight to Kochi. Before we boarded, I rang up the Thrissur Medical College principal and the DMO Dr Reena, and asked them to set up a meeting with all the key stakeholders in the district. By the time we reached Thrissur it was almost 12.15 a.m.; they were ready and waiting. The media, which had got a hint of the situation, was there too. I told them we’d brief them in the morning, but they said they’d wait.

There were more than sixty people at that meeting. It was really late but I think it was the adrenaline, from fear and expectation, that kept me going. On the one hand, we’d already dealt successfully with Nipah, so there was some clarity on how to get going with a response, but at the same time, this virus was highly contagious. My team was definitely more confident about how to move forward than when faced with Nipah: the practice and process established in 2018 guided them now. We established expert groups that would monitor key functions. In order to create the Nipah protocol we’d looked at the Ebola protocol as a guide. Now, with COVID, we referenced the Nipah protocol, making changes based on what we already understood about the disease. The incubation period for both was almost the same; however, it was believed that Nipah was only transmitted from symptomatic patients, while it was said that COVID spread through asymptomatic carriers as well. That made COVID far more infectious. So we based the protocol and the SOPs on these factors.

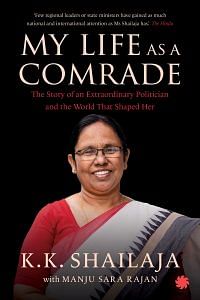

This excerpt from ‘My Life As A Comrade: The Story of an Extraordinary Politician and the World That Shaped Her’, written by KK Shailaja with Manju Sara Rajan, has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

This excerpt from ‘My Life As A Comrade: The Story of an Extraordinary Politician and the World That Shaped Her’, written by KK Shailaja with Manju Sara Rajan, has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.