Kayasthas have traditionally been a writing caste, who have fulfilled the function of record-keepers and bureaucrats. They were adept at picking up the languages of the ruling class in the places they found themselves. During Mughal rule, for instance, they had to master written and spoken Persian. They were often the interlocutors between the Muslim rulers and their Hindu subjects. Considering their penchant for language, Kayasthas have left their mark on Persian, Urdu and Hindi literature.

In the early 1700s, the first Nizam brought many Kayasthas and Brahmo-Khatris with him as he broke away from a weakened Mughal Empire and consolidated his own dominion down south. Since then, Kayasthas have been a key part of every subsequent Nizam’s administration.

A Sense of Belonging

When it came to marriages, educational institutions, professional and political associations among Kayasthas in Asaf Jahi Hyderabad—the sub-caste mattered a lot. In the late 1800s, Brahmo-Khatris and Mathur Kayasthas opened their own school in Old City, where they imparted Western education. The Mathurs and Srivastavas had their own associations as did the Saxenas of Hussaini Alam. During the 1930s, a Mathur–Saxena marriage was seen as taboo.

Partly due to the early efforts of Gaya Pershad and his mentor Kunwar Bahadur in the late 1800s, such rigidity among various sub-castes began to loosen. Post-Police Action, exclusive organizations based on these groupings were far and few between, but in 1970, the Mathur Kayasthas formed the Hyderabad Mathur Kayasth Education and Welfare Society (HMKEWS). The society leads entrepreneurship and education initiatives for their biradari members.

A few months after Narayan Raj’s death, I spoke to a well-known Hyderabadi physician, Dr Ravi Karan, whose wife was related to Saxena. Born in 1944, he grew up in a Hyderabad that was rising from the ashes of Police Action.

Ravi, whose in-laws are Saxenas, had a defined view on the trajectory of the Kayastha community, from Police Action to the present-day. He is also a former HMKEWS president; he now serves as an advisor.

Be it in Karen Leonard’s book or during our conversation, he made one observation clear: Kayasthas had not quite taken to Telugu.

‘After 1948, it was hard to get a government job without knowing English. With Telugu, one could not do much back then. Nowadays, it helps for bureaucratic or political careers,’ Ravi Karan said. ‘For the past seventy-five years, Kayasthas have not imbibed Telugu with the alacrity with which they picked up Urdu, English and Hindi. Hence, their lack of presence in the politics and bureaucracy in a united Andhra Pradesh or a newly formed Telangana.’

Through the Mulki agitation and the statehood movement in the 1950s and 1960s, English remained the more prestigious and useful language for pursuing an education. Telugu began to gain more importance from the 1970s onwards with the advent of NTR. ‘English was necessary, but the 1970s and 1980s saw more prominence of Telugu,’ Ravi Karan noted, ‘I am perplexed as to why we did not incline our youth towards Telugu thirty years ago like we did with Persian, Urdu and Hindi.’

He then brought up an interesting question. ‘What if a “son of the soil” movement emerges here?’ Ravi Karan asked, perhaps alluding to frequent news from the neighbouring state of Karnataka, ‘Kayasthas will stand to lose out on opportunities in business as well as the bureaucracy if we do not adopt Telugu. Thus, 70 to 80 per cent of qualified youngsters are now settled in the US, the UK and Canada due to the sense of belonging being very up and down here.’

Although it had been more than a few months since Narayan Raj Saxena died, when Karan spoke about this very real feeling of belonging, I immediately thought of the anonymous response from the younger Mathur Kayastha to which Bansi Raja’s great-grandson took exception. Maybe this fluctuating sense of belonging that Dr Karan spoke of explains that youngster’s response, which is quoted in the third edition of Social History of an Indian Caste.

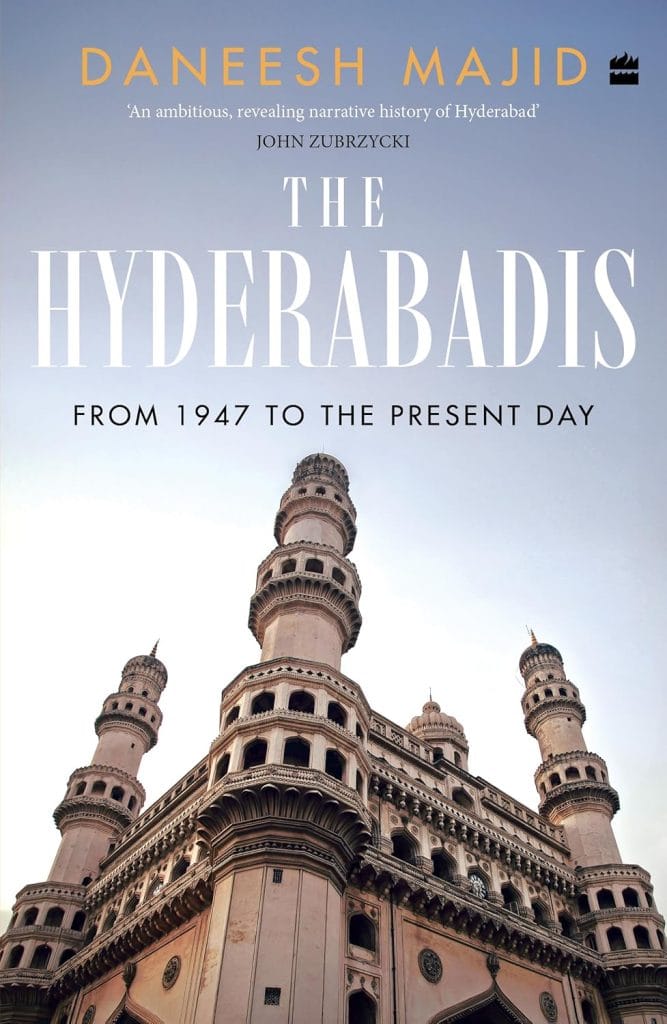

This excerpt from The Hyderbadis: From 1947 to the Present Day by Daneesh Majid has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from The Hyderbadis: From 1947 to the Present Day by Daneesh Majid has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.